Artificial intelligence (AI) is already reshaping how economies produce, trade and grow. The World Trade Report 2025, launched at the WTO Public Forum on 17 September, examines the profound ways in which AI could transform global trade. The report's findings are clear: AI has the potential to accelerate growth and expand trade opportunities, but the extent to which these benefits are shared across and within economies will depend on the choices policymakers make today.

The “40 by 40” effect

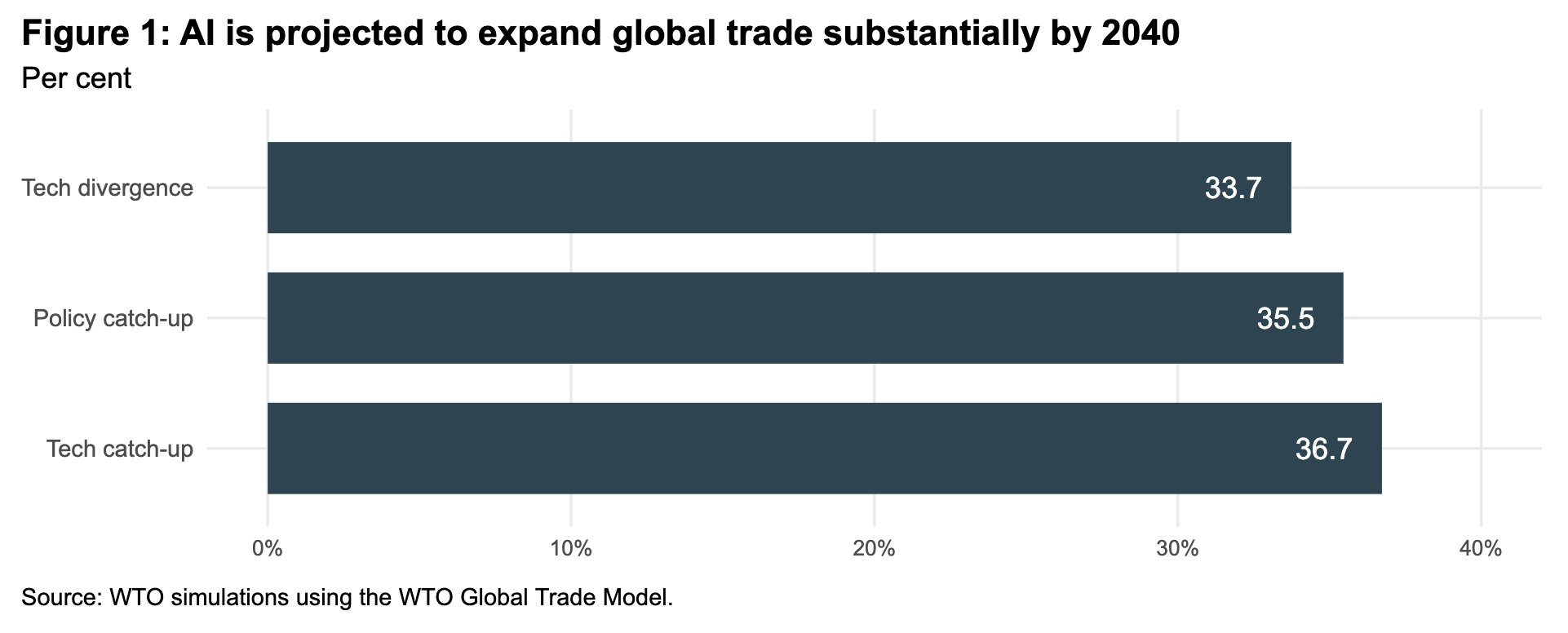

In the World Trade Report 2025, WTO economists look into the potential of AI to expand global trade based on various scenarios of technological catch-up between economies (see below). Their findings suggest that AI could increase global trade by between 34 and 37 per cent (see Figure 1), meaning that by 2040, the value of trade could be nearly 40 per cent higher than in a world without AI-driven advances. This “40 by 40” effect would stem from three powerful forces working together: lower trade costs due to AI-related efficiency gains, the rapid growth of tradable AI services, and stronger AI-driven productivity gains in sectors most integrated into international trade.

The economic impact extends beyond trade. By 2040, global GDP could be 12 to 13 per cent higher as a result of AI’s ability to boost productivity and ease the frictions that currently slow cross-border commerce.

These projections are optimistic for two main reasons. First, recent studies suggest that AI could deliver larger productivity gains than previously anticipated, substantially increasing the efficiency with which economies turn inputs such as labour into output. Second, AI is now expected to have a bigger impact on lowering trade costs, which would amplify its positive effect on growth.

Emerging AI value chains

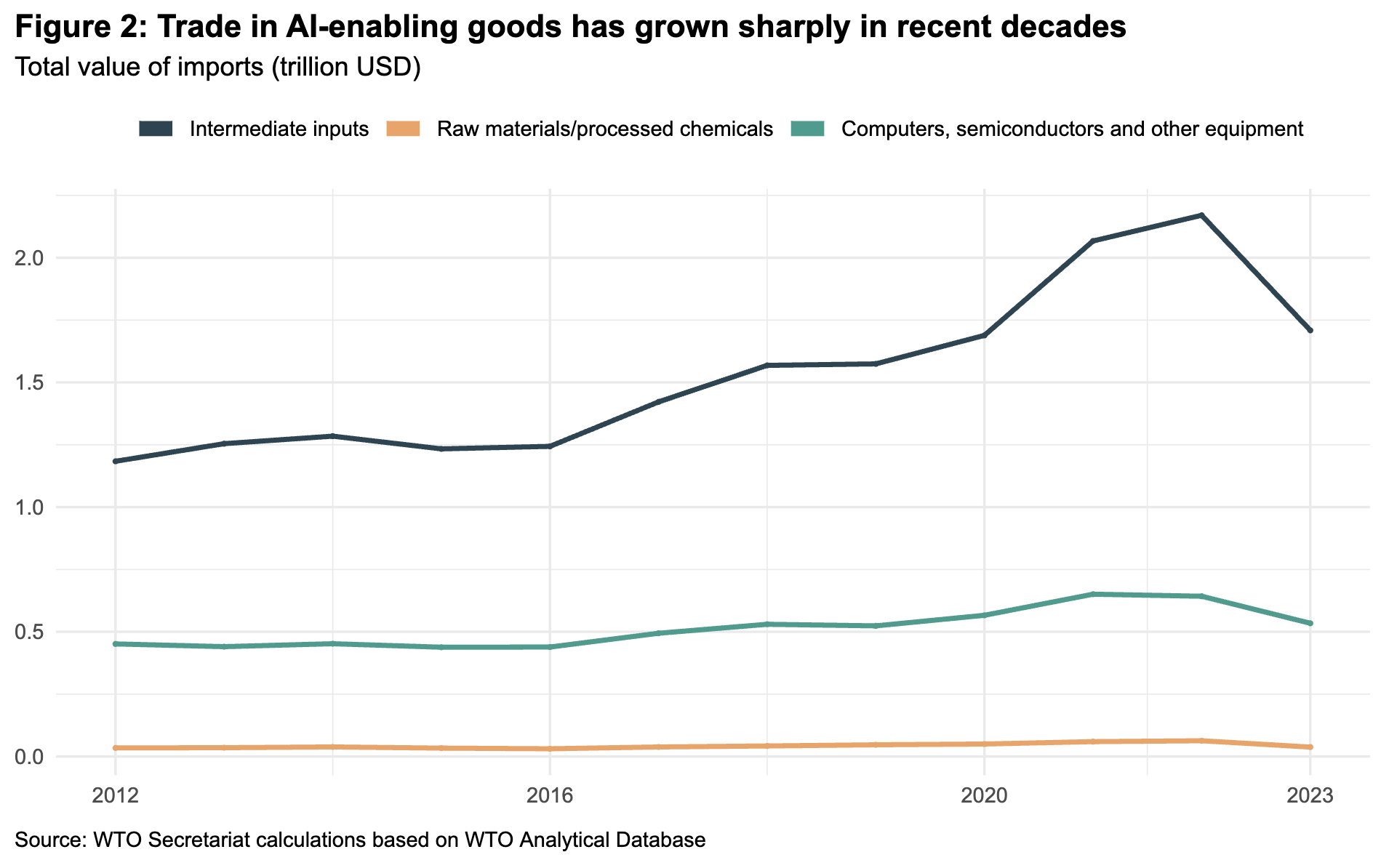

AI is already reshaping trade flows. Global trade in AI-enabling goods – such as critical minerals, semiconductors and computing equipment – reached US$ 2.3 trillion in 2023 (see Figure 2). These goods form the backbone of AI innovation, and ensuring that they are widely available and affordable will be critical to increase access to the technology.

Participation in AI value chains opens a wide range of development opportunities. Some economies are emerging as hubs for upstream inputs (i.e., at the beginning of the value chain), such as critical minerals and energy. Others are positioning themselves as centres for data hosting or cloud services, or to operate the local adaptation of AI models.

Even foundational inputs, such as training data, offer entry points for less technologically advanced economies. Ensuring fair compensation and adequate labour protections will be essential as these opportunities evolve.

The divide that could hold back growth

The opportunities of AI will not materialize automatically. The 2025 World Trade Report underscores the persistent digital divide in technology levels between advanced and developing economies.

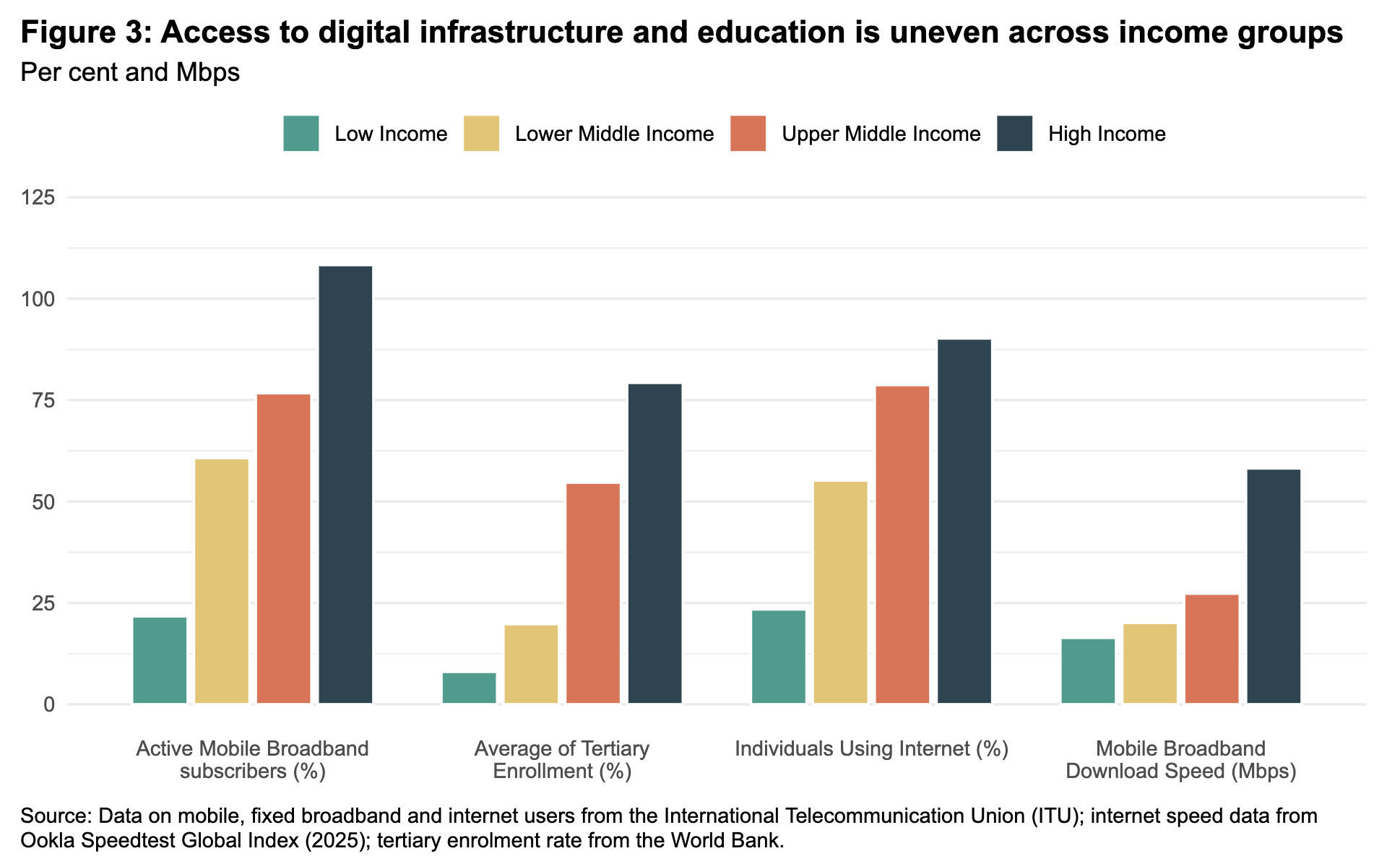

For example, internet access is nearly universal in high-income economies, while in low-income economies, only about one in five people have access to the internet. For those that do have access, connections are often slower and more expensive than in high-income economies. Education gaps deepen this divide: tertiary enrolment and the share of graduates in science and technology subjects remain much lower in poorer economies (see Figure 3).

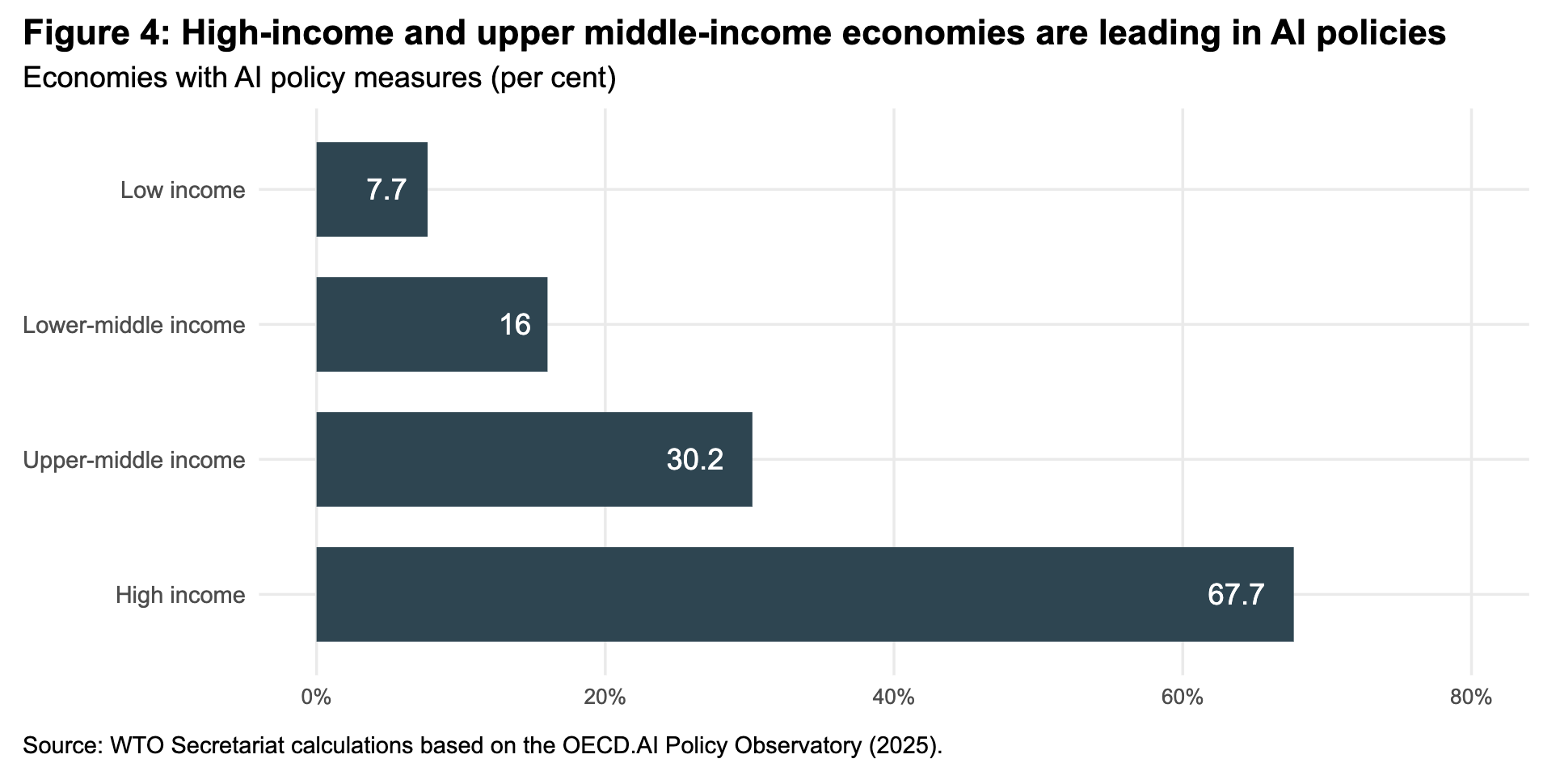

Policy differences add further challenges. Almost 70 per cent of high-income economies have adopted AI policies, compared to just 8 per cent of low-income economies (see Figure 4). Spending on labour market programmes also shows significant divergences. While wealthier economies can provide meaningful income support and retraining to workers displaced by AI, poorer economies struggle to offer even minimal assistance.

Figure 4: High-income and upper middle-income economies are leading in AI policies

High-income and upper middle-income economies also spend far more than lower-income economies on AI education and labour market programmes for workers displaced by AI. As of 2025, less than one-third of developing economies had adopted dedicated AI education strategies. High-income economies also provide much stronger social and labour support. These gaps provide a stark reminder of the challenges that many governments face in effectively supporting workers displaced by technological change.

The future of inclusive growth depends on policy choices made today

The future of AI is defined by uncertainty – not only concerning how the technology itself will evolve, but also with regard to how governments and policymakers will respond to AI. If governments are to unlock the potential of AI for inclusive growth, they will need to bridge digital divides, invest in education and skills, reinforce labour market adjustment policies and ensure that trade remains open and predictable.

To capture this complexity, the World Trade Report explored various scenarios:

Scenario 1: Technology divergence remains at the current level: According to this scenario, AI adoption could widen existing divides. High-skilled workers would capture most of the gains as AI-related productivity rises, while differences in digital infrastructure and policy choices would shape how much individual economies benefit from reduced trade costs and efficiency improvements.

Scenario 2: Policy catch-up between economies: According to this scenario, governments in less digitally advanced economies could reduce by half the gap in AI-related infrastructure and policy compared to the frontrunners. AI technology is also more widespread in this scenario. At the same time, the use of "basic AI" means that medium-skilled workers see the largest productivity boost, and the benefits of AI are more widely shared.

Scenario 3: Technology catch-up between economies: Building on Scenario 2, faster technological diffusion allows productivity levels in AI-enabled tasks in less digitally advanced economies to converge partially with the productivity levels of the best-performing regions, helping lagging economies to close the gap further.

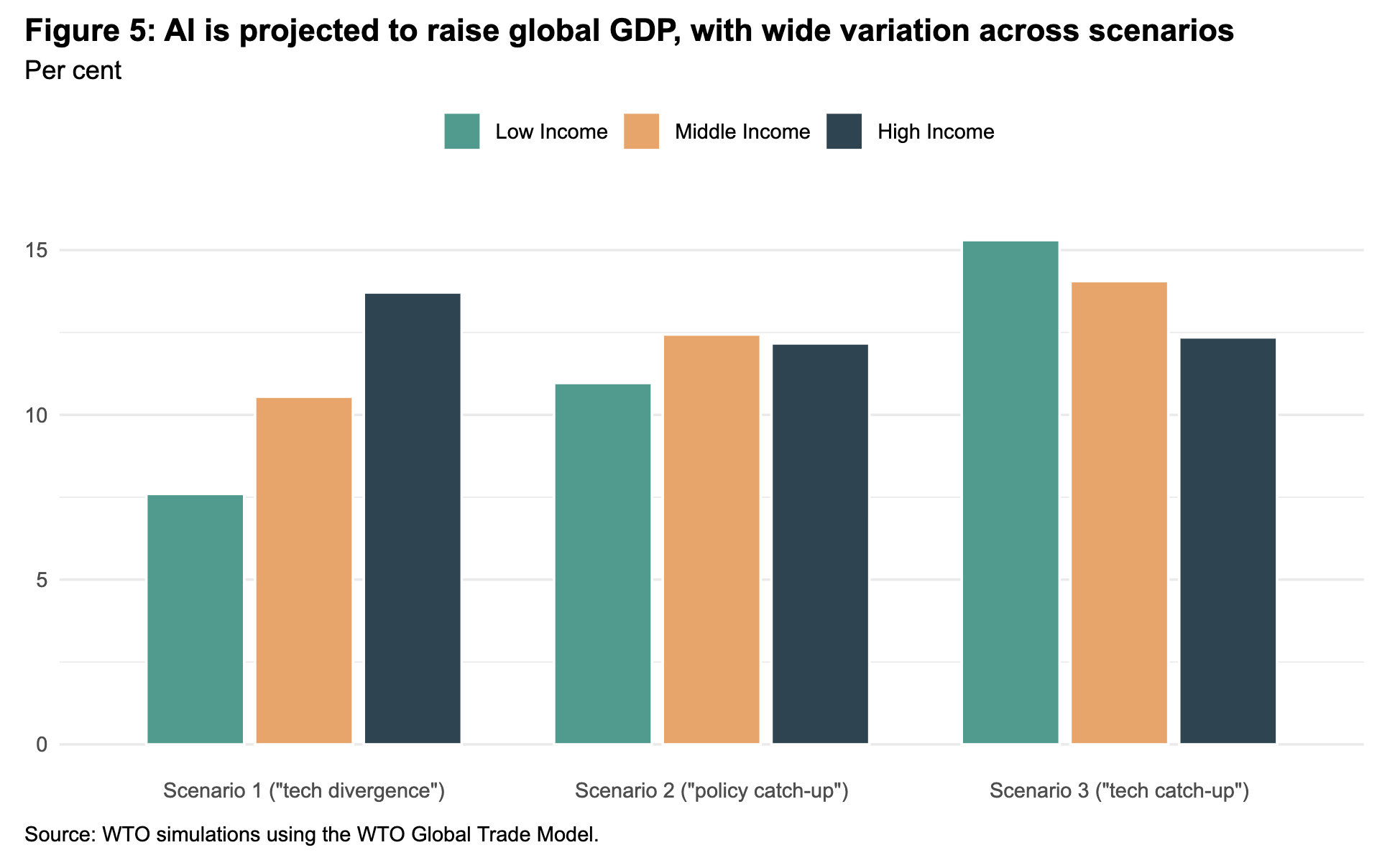

The differences are significant. As shown in Figure 5, if digital and AI divides are narrowed (per Scenario 3: Technology catch-up), this could almost double the GDP gains for low-income economies, from 8 per cent in a scenario with no catch-up (per Scenario 1: Technology divergence) to 15 per cent, without substantially changing the growth prospects in higher-income economies.

These differences arise because moving from Scenario 1 (Technology divergence) to Scenario 2 (Policy catch-up) and Scenario 3 (Technology catch-up) involves two simultaneous changes.

First, low-income economies would need to strengthen their digital infrastructure, as this would enable them to achieve larger productivity gains.

Second, the model shifts from a world dominated by “advanced AI”, where most of the benefits accrue to high-skilled workers, to one in which “basic AI” plays a greater role, delivering higher productivity gains for low-skilled and medium-skilled workers. As high-income economies depend more heavily on high-skilled labour, their average productivity gains are slightly reduced. At the same time, the wider adoption of basic AI tools can help reduce inequality within economies.

The World Trade Report 2025 also considered a fourth scenario based on AI technological catch-up between economies, i.e., economies with low productivity in AI services partially catch up with economies with high productivity in these services. For the sake of simplicity, this blog post discusses only the first three scenarios in the Report.

The role of trade and cooperation

Trade can act as a powerful equalizer. By facilitating access to AI technologies, skills and inputs, open trade can ensure that the benefits of AI are more widely shared. Tariffs, export measures, services regulation and data governance will all shape the availability, affordability and diffusion of AI and AI-enabling goods and services.

The WTO agreements already support AI development by promoting open markets, protecting innovation and encouraging regulatory coherence. But more can be done, for example by easing access to AI-related goods and services, reducing regulatory fragmentation and using AI responsibly in the implementation of trade disciplines.

Given that many AI-related trade challenges touch on broader policy domains, stronger cross-institutional collaboration will also be essential to ensure that trade, competition, labour and environmental policies can reinforce one another.