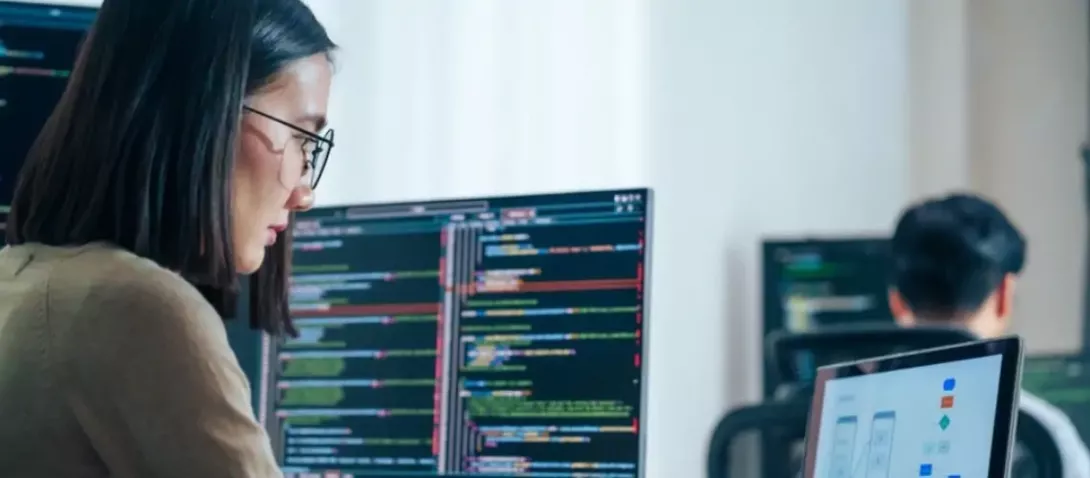

GenAI is set to have a significant impact on white-collar jobs within high-skill services sectors. | © Shutterstock

Youth unemployment and underemployment are growing challenges worldwide, especially for college graduates. Families have long invested in higher education for their children, dreaming of careers in fields that require specific skills and expertise like law, banking, engineering, or diplomacy. College enrollment rates surged, tripling from 14% in 1990 to 42% in 2022. Yet, many of these ambitions have not materialized. In 2023, one in five young people globally were not in employment, education, or training, with women making up two-thirds of this group. In the United States, over half of recent college graduates are in jobs that do not require a college degree.

The lack of productive and stable white-collar jobs for those with university diplomas is especially acute in developing economies, where the creation of such jobs lags. In low- and lower-middle-income countries, more than a fifth of those under age 30 who have postsecondary qualifications are unemployed, much higher than those with a basic education. In Sub-Saharan Africa, nearly three out of four young adult workers aged 25 to 29 were in insecure jobs – meaning they were either self-employed or in temporary positions. In the Arab States and North Africa, one in three economically active youth are unemployed. China also experienced a significant spike in its official youth unemployment rate in recent years, surpassing 20% in June 2023.

As this crisis unfolds, a new player has entered the job market: Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI). Will it be the solution we’ve been waiting for, or will it exacerbate an already dire situation? Our recent working paper examines how GenAI might affect the economy – its growth, changes in industry structure, and international production patterns. Here’s what we discovered:

1. GenAI predominantly boosts productivity in high-skill services

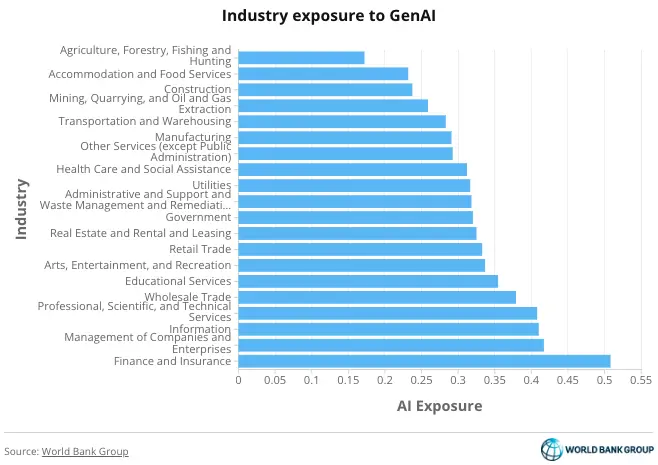

GenAI is set to have a significant impact on white-collar jobs within high-skill services sectors, which are typically filled by those with a college education. Unlike previous waves of digital technologies, which primarily expedited routine tasks or made predictions by recognizing data patterns, GenAI’s ability to synthesize and generate ideas and content intersects with a substantial portion of tasks in white-collar occupations. Several studies consistently indicate that the jobs most exposed to GenAI are concentrated in high-skill services (Eloundou et al. 2023; Gmyrek, Berg, and Bescond 2023; World Economic Forum 2023; Melina et al. 2024). Our findings reveal that finance and insurance, ICT services, and professional services—three high-skill, high-income, and highly digitalized industries—are the most vulnerable to the influence of GenAI.

2. The struggle to create good jobs in developing countries

As automation makes manufacturing-led growth increasingly elusive, many low- and middle-income countries are pinning their hopes on high-skill services. However, these sectors struggle to generate substantial employment opportunities for their growing youth population. While many countries have experienced rapid upticks in high-skill services due to accelerating digital transformation, this growth has moderated or stagnated in several nations, including the United States, the largest exporter of high-skill services.

In middle- and low-income countries, the share of employment in high-skill services has also stalled in countries like Mexico, Türkiye, Bolivia, the Philippines, and Vietnam in recent years. Approximately 13%-20% of the workforce in high-income countries is engaged in high-skill services, but this share drops considerably to 6%-10% in upper middle-income countries and plummets further to just 0%-4% in lower middle- and low-income countries. Notably, even in developing countries recognized for their high-skill services exports, such as India and the Philippines, this sector contributes a surprisingly modest share to overall employment, accounting for no more than 3% of jobs.

3. GenAI: Growth driver or harbinger of premature de-professionalization?

Our paper simulates the potential impact of AI. The simulations show some surprising and concerning results.

- Unless AI is widely adopted across sectors and drives transformative innovations that permanently shift consumer preferences, its short-term growth benefits will likely be underwhelming.

- The share of employment in high-skill services may eventually stagnate or decline, following a hump-shaped curve similar to manufacturing. While higher income increases demand for high-skill services, advancements in AI could reduce the need for white-collar workers, shifting job concentration toward low-skill services.

- AI could further constrain the potential for creating quality jobs in high-skill services, particularly in developing countries. Similar to premature de-industrialization, AI may lead to “premature de-professionalization”, where employment share in high-skill services peaks earlier and at lower income levels.

- Low- and middle-income countries face a critical juncture with AI adoption. Failure or delay in embracing AI risks eroding existing comparative advantages in high-skill services and manufacturing, or hindering the development of such advantages. Consequently, these countries may find themselves trapped as commodity exporters, with employment heavily concentrated in agriculture and low-skill services. Conversely, successful and timely AI adoption could catalyze the development of new competitive edges in the high-skill service sector or manufacturing.

The path forward

Developing countries urgently need to embrace AI to gain an edge in more complex, growth-boosting sectors. Right now, AI is in its early stages, driving up demand for high-skill service jobs. But this opportunity won’t last forever.

The stakes for developing countries are immense. Those slow to adopt AI may risk greater difficulties in creating quality jobs, trapping their young people in cycles of unemployment, underemployment, and stagnant living standards. Over the next decade, an unprecedented 1.2 billion young people in the Global South will reach working age. The future of work – and the aspirations of billions – hang in the balance.