Making trade more inclusive is a key priority for WTO members. Their shared goal is to ensure that trade benefits more economies and more people, building on the vision articulated in the preamble of the WTO’s founding Marrakesh Agreement. The 30th anniversary of this agreement provides a natural opportunity to review past progress, assess current trends and identify the path forward towards making trade work for all.

This is precisely the focus of the World Trade Report 2024, which we are launching today (10 September). The report seeks to answer three key questions: How can we make trade work for more economies? How can we make trade work for more people? And how can the WTO better support these goals?

The report reaches three main conclusions. First, trade has a strong track record as a driver of inclusiveness. Second, despite this success, too many economies and people remain left behind. Third, bridging this gap requires a comprehensive strategy — one that integrates open trade with complementary domestic policies and fosters greater international cooperation.

For the WTO, this suggests a particular focus on policy coherence. The complex “trade and” challenges we face today given mega-trends like climate change, digital transformation and geopolitical tensions demand a “WTO and” approach, where collaboration with other international organizations ensures that trade policies are effectively integrated with broader international and domestic policy frameworks.

Trade as a driver of inclusiveness

To begin with, consider the first main insight of the report: trade has been a powerful driver of inclusiveness.

Since the WTO was established 30 years ago, the gap in income levels between economies has dramatically narrowed. Since 1995, per capita incomes in low- and middle-income economies have nearly tripled, while global per capita income has grown by approximately 65 per cent. However, this convergence process has slowed since the global financial crisis and even reversed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which hit growth in poorer economies the hardest.

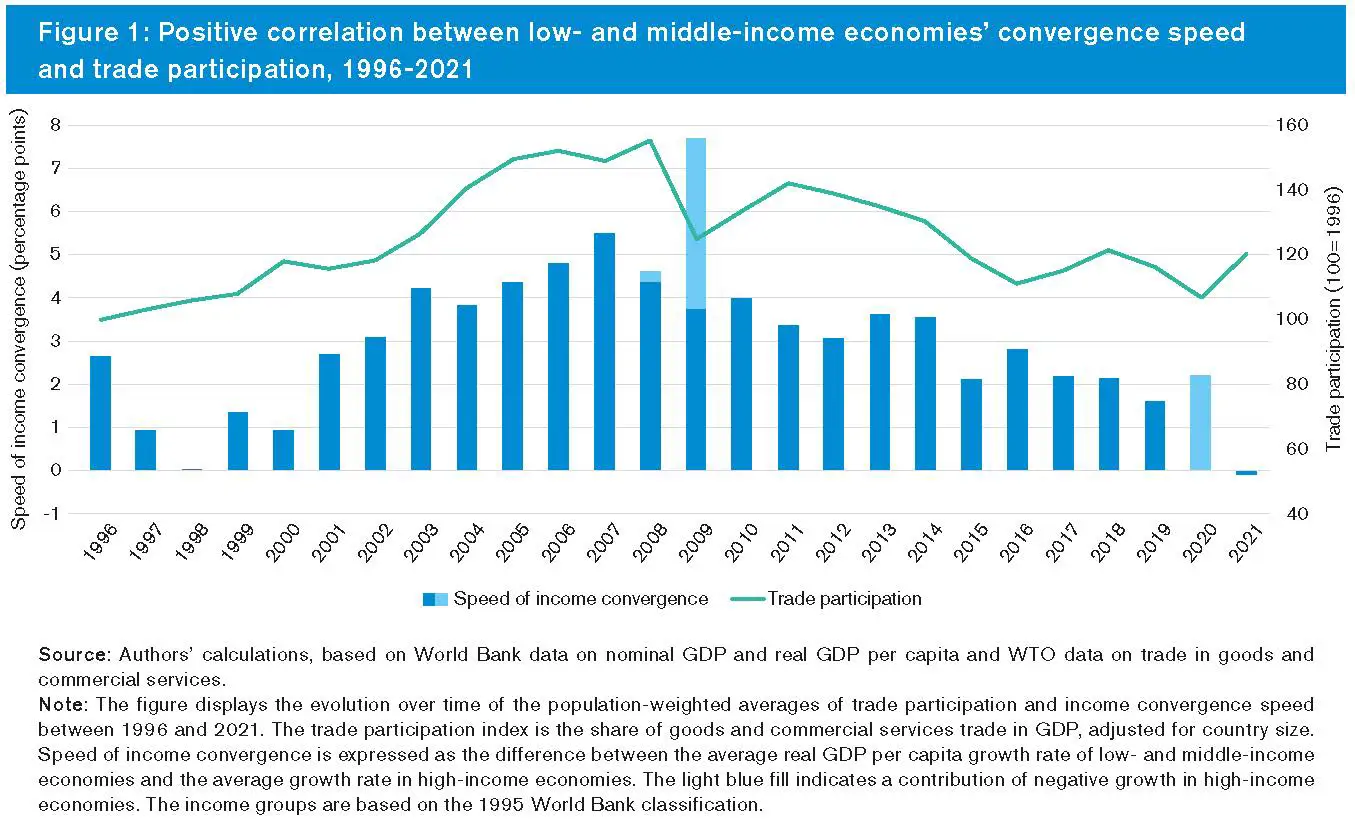

The correlation between the convergence speed of low- and middle-income economies and their trade participation is striking. As shown in Figure 1, both metrics rose and fell in tandem before and after the global financial crisis. Economic research indicates that this is more than just a correlation. Simulation analysis suggests that trade cost reductions between 1995 and 2020 led to a 20 to 35 per cent faster income convergence of low- and middle-income economies. This finding aligns with econometric evidence showing that trade reforms in developing economies have boosted economic growth by 1 to 1.5 percentage points.

The evidence on the direct effect of WTO membership is also positive. Recent research indicates that membership in the WTO (and its predecessor the GATT) has boosted trade between members by an average of 140 per cent, underscoring the benefits of an open, rules-based and predictable multilateral trading system. As illustrated in Figure 2, econometric analysis further suggests that economies undergoing rigorous accession negotiations grew 1.5 percentage points faster during the accession period, driven by the governance reforms required to meet WTO rules.

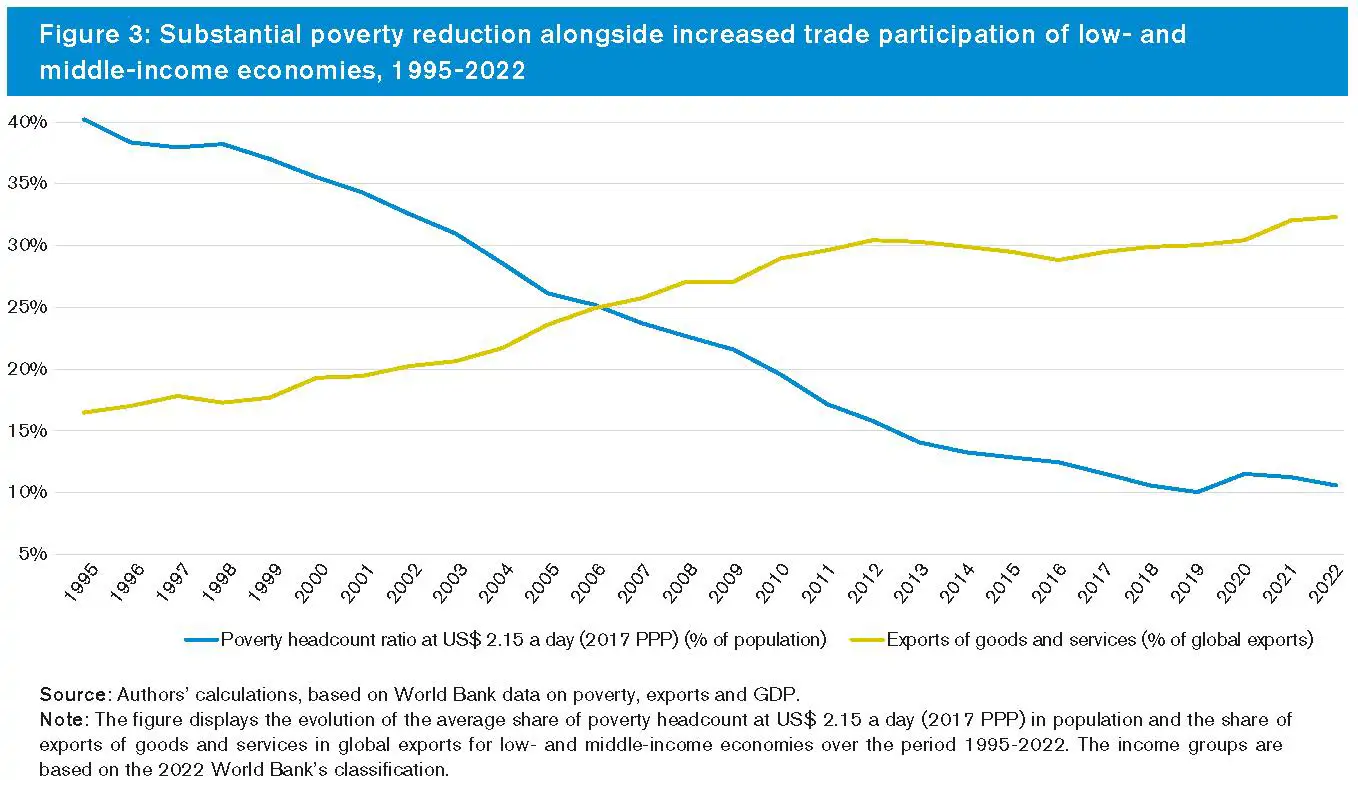

This trade-led convergence has improved the lives of hundreds of millions of people. As shown in Figure 3, the share of people living in extreme poverty in low- and middle-income economies has dropped from 40 per cent to around 11 per cent since 1995, while the share of trade in these economies’ GDP has doubled from about 16 per cent to 32 per cent. This shift has significantly contributed to reducing malnutrition and infant mortality, as well as improving access to education, healthcare and electricity.

Contrary to common belief, income inequality within economies has not increased on average over the past 30 years. The average Gini index — a common measure of inequality — across a broad range of economies has even declined slightly during this period. Moreover, income inequality is only weakly correlated with trade openness and is slightly lower in more open economies. This aligns with economic theory, which suggests that while trade creates both winners and losers, it does not inherently lead to greater income inequality.

Recent evidence also challenges the common perception that import competition in industrialized countries has led only to losses, instead revealing significant gains as well. In the United States, while some manufacturing regions have seen income declines after increased trade with China, regions focused on agriculture and services have experienced income gains. Similarly, in Germany, areas with import-competing sectors like textiles have faced employment losses, but regions specializing in sectors like automobiles have expanded following increased trade with China and Central Eastern Europe.

While the responsibility for addressing inclusiveness within economies primarily lies with national governments, WTO members are increasingly collaborating in this area. This includes efforts through the WTO Informal Working Groups on Micro-, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (MSMEs) and Trade and Gender. Additionally, poverty reduction, women’s economic empowerment and MSMEs’ participation in world trade are being increasingly integrated into technical and capacity-building initiatives like Aid for Trade, the Enhanced Integrated Framework and the Standards and Trade Development Facility.

Too many economies and people are still left behind

Next, consider the second main insight of the report: too many economies and people are still being left behind.

Income convergence and global economic integration have been uneven, leaving some economies behind. Between 1996 and 2021, one-third of low- and middle-income economies, representing 13 per cent of the global population, grew slower than the average high-income economy in per capita terms, leading to divergence rather than convergence. These diverging economies are mostly located in Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East. In addition, some of the converging economies are catching up very slowly. If they were to grow at the same pace as in the past three decades, a third of low-income converging economies would still not reach middle-income status within the next three decades.

While each diverging economy has its own unique characteristics, they can be broadly categorized into two groups. Three-quarters of diverging economies have trade participation below the average for their income group. The remaining quarter shows relatively high trade participation but is primarily specialized in commodity exports. Therefore, the report identifies low trade participation and high commodity dependence as key risk factors for divergence. These economies also receive considerably less foreign direct investment (FDI) than their peers, which is not surprising given that trade participation and diversification are often intertwined with the production activities of multinational firms.

High trade costs are a key factor driving the low trade participation of some diverging economies. The WTO Trade Cost Index, which measures the frictions remaining in international trade relative to domestic trade, reveals that trade costs are significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in manufacturing and services. This disparity is especially pronounced for least-developed countries (LDCs), where trade costs are 47 per cent higher in manufacturing and 50 per cent higher in services compared to high-income countries. Unlike other regions, Africa and the Middle East face the added challenge of higher trade costs when trading within their own regions compared to partners from outside.

Trade policies are a significant driver of high trade costs. Poorer economies often face high costs in utilizing foreign trade preferences or complying with foreign standards, and they tend to impose higher tariffs, with less progress in implementing trade facilitation measures. However, complementary domestic policies also play a critical role. Issues like underdeveloped infrastructure, inefficient electricity and telecommunication services, and weak contract enforcement further hamper trade.

Resource-rich economies often struggle to diversify beyond their main export commodity, a challenge known as the Dutch Disease. This occurs when thriving commodity exports make it difficult to establish competitive manufacturing or agriculture sectors. Barriers to FDI, including explicit restrictions and “soft” factors like an unfavourable investment climate, exacerbate this challenge. Additionally, tariff escalation in export markets, where tariffs increase from raw materials to semi-processed goods and are highest on finished products, can prevent developing economies from diversifying into higher value-added products.

Just as too many economies are left behind, so are too many people. One aspect that receives particular attention is within-country inequality, which despite the slight decline over the last 30 years remains high in absolute terms. For example, the average Gini coefficient today is similar to that of the early 1900s. Moreover, the top 1 per cent of earners across all economies still receive an average of 15.8 per cent of total income.

It is thus understandable that discussions about trade and inclusiveness are often framed as debates about trade and inequality. However, as we have established, trade integration is not strongly correlated with inequality; it increases inequality in some economies while reducing it in others. A more helpful approach is to examine how fairly the gains from trade are shared. Shifting trade dynamics create winners and losers, as almost any economic change does. Problems arise when the losses are highly concentrated, even if the overall gains outweigh them, as they typically do.

A crucial yet often overlooked aspect of the gains from trade is the consumer benefits from lower prices and increased product variety. Research shows that these gains disproportionately benefit low-income households, who spend more on imported goods like food and less on non-traded services such as dining out. However, these benefits do not always reach all consumers, often due to uncompetitive distribution sectors that capture the surplus from falling prices, or high internal trade costs that make traded goods expensive in remote areas.

These consumer benefits arise from productivity gains as workers and capital move from less productive to more productive firms, sectors or regions, leveraging comparative advantages and economies of scale. Conversely, less productive firms, sectors or regions lose resources due to import competition. While this aspect often dominates public discussion, it is important to put it into context. WTO calculations based on OECD data suggest that less than 2 per cent of the population is affected by import competition in the 14 most populous economies covered in the database.

The net impact of trade on individual workers is the result of a combination of import competition, access to cheaper foreign inputs and export opportunities. These three channels operate at various levels — occupation, sector and region — creating a wide range of potential impacts. For example, a worker in an import-competing region may be employed by a large exporting firm that sources a significant share of inputs from abroad, with the benefits of cheaper inputs and enhanced export opportunities potentially offsetting the impact of import competition.

The multilayered effects of trade on workers imply that these impacts will vary widely across economies and even among similar workers. But one thing is clear: protectionism is not an effective policy for protecting workers, as it often leads to unintended consequences. For instance, while higher tariffs may protect jobs in import-competing sectors, they can also jeopardize jobs in sectors that rely on intermediate inputs or are export-oriented if trading partners retaliate. Additionally, tariffs tend to be a regressive tax, disproportionately affecting the poorest.

What truly hinders a fair distribution of the gains from trade are the barriers that prevent workers from moving towards new opportunities. Studies indicate that the costs for workers to switch sectors or occupations after trade shocks can be equivalent to several times their annual wage. While these costs are significant everywhere, they are especially pronounced in developing economies, where they are, on average, 33 per cent higher than in high-income economies.

The report thus takes an in-depth look at these barriers, emphasizing that most are rooted in domestic policies rather than trade policy. Key barriers include limited access to education, underdeveloped capital markets, excessive labour market regulations, high labour market informality, and significant market power in product and labour markets. Evidence consistently shows that these barriers disproportionately affect four groups: women, MSMEs, unskilled workers, and those in rural or remote areas.

Addressing the gap requires a comprehensive strategy

The bottom line of our analysis is this: less trade will not promote inclusiveness, nor will trade alone. True inclusiveness demands a comprehensive strategy — one that integrates open trade with supportive domestic policies and effective international cooperation. This is the third main insight of the report.

For the WTO, the obvious priority is to maintain an open, predictable and non-discriminatory multilateral trading system — a task that is increasingly challenging in today’s environment. This involves restoring a fully functioning and accessible dispute settlement system, a goal that WTO members are actively working towards.

But the report also suggests a focus on policy coherence. The complex “trade and” challenges we face today given mega-trends like climate change, digital transformation and geopolitical tensions demand a “WTO and” approach, where collaboration with other international organizations ensures that trade policies are effectively integrated with broader international and domestic policy frameworks.

Digital trade, for instance, offers significant potential not only for less integrated economies but also for MSMEs and women. However, these opportunities can only be realized with the right complementary investments, such as in education and digital infrastructure. International initiatives leveraging the specific expertise of different international organizations can catalyze more inclusive digital trade.

Beyond this broad point, the report identifies three key areas where the WTO can help ensure that more economies and people benefit from trade.

The first area is cooperation on the implementation of WTO agreements. This includes efforts to support the implementation of existing commitments, such as those in the Trade Facilitation Agreement, which could boost the participation of LDCs and MSMEs in trade. It also involves finding the right balance between commitments and flexibilities when invoking special and differential treatment, keeping in mind that both are crucial for unlocking the development gains from trade.

The second area is updating the rulebook to reflect that the future of trade is in services, is digital and is green. WTO members have already made significant progress in this direction through agreements on services domestic regulation, investment facilitation for development, e-commerce and fisheries subsidies. However, many services sectors still face significant restrictions, low-income economies have limited participation in digital trade, and trade-related environmental policies lack coordination.

The third area is enhancing information sharing. Sharing information, best practices and conducting data collection and analysis can help implement WTO agreements more inclusively. However, this approach is only effective if the WTO itself remains inclusive. Members are actively working to improve the participation of LDCs in WTO activities through ongoing “reform by doing” initiatives. Additionally, efforts are being made to increase the involvement of vulnerable groups in WTO discussions, with platforms like the WTO Public Forum playing a crucial role.

To summarize, the report comes to three main conclusions. First, trade has a strong track record as a driver of inclusiveness. Second, despite this success, too many economies and people remain left behind. Third, bridging this gap requires a comprehensive strategy — one that integrates open trade with complementary domestic policies and fosters greater international cooperation.

The full report is available here.