The Docks in St. Peter Port, Guernsey. (Image: @enrapture via Unsplash)

To mitigate the risk of being left behind, developing countries should adopt frontier technologies while diversifying their economies.

We stand on the brink of a new technological revolution that could entrench or further exacerbate the great divide between countries, which manifested itself after the First Industrial Revolution. Only a handful of countries produce the technologies that are driving this new revolution, but all countries will be impacted by it. However, virtually no country is well prepared to deal with the consequences of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. As we reached this critical crossroads, more than ever holistic leadership is needed to ensure development-friendly outcomes and impact of the new technological wave.

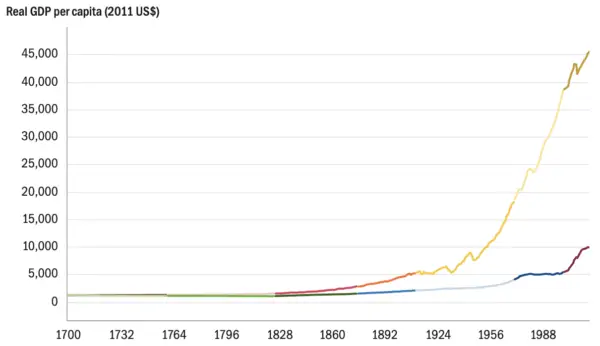

UNCTAD’s recent Technology and Innovation Report 2021 asserts that income disparity in the world prior to the First Industrial Revolution was minimal (figure below). Since then, every wave of technological change has further deepened the inequality between countries. The average income per capita gap between developed and developing countries in 2018 was USD 40,749.1

The great divide and waves of technological change

Note: “Core” corresponds to Western Europe and its offshoots (i.e. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United States) as well as Japan. “Periphery” corresponds to the world, excluding the “core” countries.

Source: UNCTAD (2021), based on data from the Maddison Project Database (2018) , Inklaar et al. (2018), Perez (2002), and Schwab (2013).

Significant progress has certainly been made on the whole, and not only in developed countries. People are living longer and healthier lives, educational attainment has risen, and access to clean water, sanitation and electricity has improved. Yet poverty and huge disparities between countries in terms of income, education, health, etc. continue to persist. In 1820, in the early days of the First Industrial Revolution, global income inequality was a class divide limited to within countries, while it hinges today on the lottery of the individual’s birthplace2.

There is no consensus about how to interpret the dynamics of economic inequality. Numerous factors affect inequality: war, trade, globalization and epidemics such as COVID-19. Technological revolutions also have an impact on inequality. According to Carlota Perez3, such revolutions consist of two stages.

The first stage entails the installation of the new technological paradigm, which starts in a few sectors (and places) at the core of the technological wave, such as the tech sector in silicon valley during the installation of the Age of ICT. In this stage, there is the potential for increasing income inequality between the workers in these core industries of the new paradigm, including finance, and the rest. In particular, the financial sector fuels “irrational” expectations of profits in the new technology sectors and may decouple from the real economy in its search of increasingly higher gains.

The second stage is the deployment of new technologies, which tends to be uneven; not everyone gets immediate access to the benefits of progress. This could be a time of social discontent when people realize that the promises of social progress through new technologies left many people behind. It also ends in a period of merging and concentrating of power in a few firms at the core of the paradigm, which gives rise to great fortunes in the hands of a few. Furthermore, technological revolutions reach developing countries with asymmetric delays, and sometimes only usher in changes in infrastructure (e.g. internet and mobile phones) and in consumption patterns (e.g. e-commerce), but not changes in production structures, thereby increasing the technological and income gaps between developed and developing countries.

The world seems to have entered the deployment phase of the “ICT Age”, while the installation stage of a new technological paradigm built on frontier technologies4 and Industry 4.0 is already underway. The deployment of ICT has resulted in an immense concentration of wealth in the owners of major digital platforms, and the COVID-19 pandemic has further accentuated the existing digital divide within and between countries. How will this new paradigm influence the existing inequalities between countries?

Frontier technology readiness

A country’s current pattern of industrial activity could inform its likelihood of adopting frontier technologies.

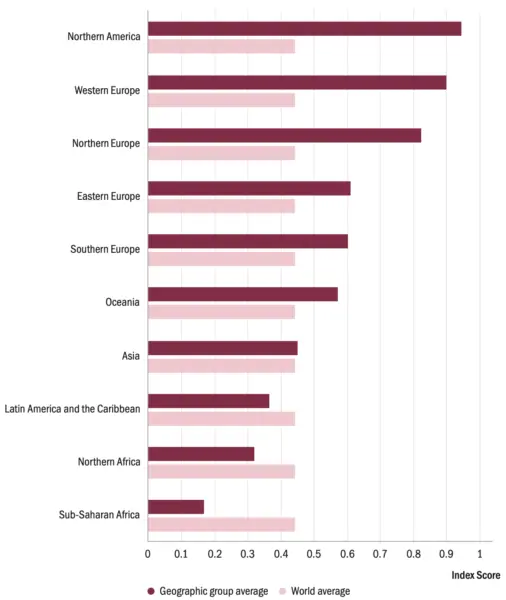

Only a few countries currently invent and produce frontier technologies, but all countries will need to get ready to embrace them. UNCTAD’s Technology and Innovation Report 2021 introduces a readiness index to assess national capabilities to equitably use, adopt and adapt these technologies. The index comprises five building blocks: (i) ICT deployment, (ii) skills, (iii) R&D activity, (iv) industry activity and (v) access to finance. The first three blocks are aligned with the national technological capacities identified by Sanjaya Lall5. Industrial activity is related to the assumption that the development of technological capabilities are path-dependent based on research on economic complexity.6 Hence, a country’s current pattern of industrial activity could inform its likelihood of adopting frontier technologies. Access to finance is considered a building block for innovation, based on a Schumpeterian view of the finance and innovation nexus.

The readiness index shows that the economies best prepared for an equitable deployment of frontier technologies are countries in Northern America and Europe, while the least prepared countries are located in sub-Saharan Africa (figure below).

A country’s current pattern of industrial activity could inform its likelihood of adopting frontier technologies.

Average frontier technology readiness index score by geographical group

Source: UNCTAD (2021).

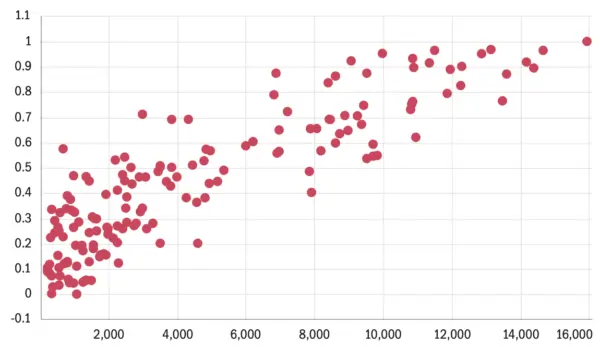

Clearly, there are many outliers, i.e. countries that perform better than their per capita GDP suggests. India, for example, is the biggest overperformer in the readiness index, ranking 65 positions higher than might be expected, followed by the Philippines, which ranks 57 positions higher than expected. The countries that are outperforming others have promoted and invested in innovation and technological learning through domestic R&D. They have also been more successful in diversifying their economy, which has created opportunities for innovation and the deployment of new technologies.

Challenges for developing countries

In 2019, around 83% of Europeans were internet users, while only 29% of the population in Africa and 19% in least developed countries were using the internet.

Developing countries face two major challenges. The first challenge is that the waves of technological change involve digital technologies. To support innovation and entrepreneurship in this field, the digital divide—which is wider in developing countries—must be addressed. In 2019, around 83 per cent of Europeans were internet users, while only 29 per cent of the population in Africa and 19 per cent in least developed countries were using the internet.7

The second challenge developing countries face is that the large waves of technological change behave like ‘real’ waves, starting in one or two of the most technologically advanced countries to then spread across the world: initially to other advanced economies, then engulfing more complex industrial sectors in emerging economies, and over time, the waves move towards more peripheral economies. The production structures of less diversified developing countries are located very far from the key industries that underpin the new technological paradigm (e.g. computers and digital products), and it will take these countries longer to deploy new technologies in their production base if they do not diversify their economies. In fact, according to UNCTAD’s index, a higher level of economic diversification is associated with a higher readiness to use, adopt and adapt frontier technologies (figure below). Therefore, promoting diversification could facilitate the deployment of the new technologies the waves are washing up.

Relationship between total GDP and economic diversification (2019)

Note: Diversification is based on the number of product categories exported at the SITC 5-digit level, further disaggregated by unit value using the methodology presented in Freire (2017).

Source: Author based on UNCTAD (2021) and UN COMTRADE data.

Implications for industrial development

Developing countries need to adopt frontier technologies while continuing to diversify their production base by mastering existing technologies.

As UNCTAD’s Technology and Innovation Report 2021 emphasizes, developing countries need to adopt frontier technologies while continuing to diversify their production base by mastering existing technologies; otherwise, they risk being left behind. The effectiveness of this approach depends on the country’s level of economic development and its economic structure. In practice, developing countries should focus on policy objectives that more closely reflect their installed production base and the maturity of the technologies they use. For example, less diversified countries should focus more on diversifying their economy, on technological learning and on mastering the technologies used in the industrial sectors the country seeks to promote in terms of job creation and value addition. Other developing countries will have to perform a balancing act, continuing to diversify their economy while addressing the potentially negative impacts on jobs that the adoption of the new technologies being promoted for the country’s production structure are likely to have.

If developing countries are to benefit from frontier technologies, they should act on the below considerations.

Developing countries should take further steps to bolster the effectiveness of their innovation systems, which tend to be weaker and more prone to systemic failures and structural deficiencies than those in developed countries. To be effective, science, technology and innovation (STI) policies need to build synergies with other economic policies (industrial, fiscal and educational policies) and involve a wide range of actors.

Aligning STI with industrial policies is crucial. The transfer and diffusion of new technologies into traditional production industries speeds up industrial structural transformation and upgrading. Countries should furthermore seek to insert their firms in new industries that lie at the frontier of technological development, which have great potential for rapid labour productivity increases.

The capabilities to adopt and adapt frontier technologies in a country’s existing production base is another key area policymakers must focus on. This cannot be achieved without education and training and the development of digital skills and competencies. Such competencies vary across sectors, countries and industrial development. Basic technical and generic skills are primarily required in countries where technological development is at an early stage. Given that science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) is driving rapid technological change, governments should facilitate women’s access to technology, participation in priority setting, policy decisions and the elaboration of research and development agendas.

In the context of frontier technologies, infrastructure—particularly digitalization and connectivity—is a key element of an enabling environment. Developing countries need to build their infrastructure with an emphasis on providing reliable access to electricity and connectivity, ensuring affordable access to information and communication technologies, and overcoming gender, generational and digital divides.

References

- UNCTAD calculations based on UNCTADstat.

- Milanovic B. (2011) A short history of global inequality: the past two centuries. Explorations in Economic History. 48(4):494–506.

- Perez C. (2002) Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Edward Elgar Pub. Cheltenham.

- The UNCTAD Technology and Innovation Report 2021 covers 11 frontier technologies: artificial intelligence (AI), the internet of things (IoT), big data, blockchain, 5G, 3D printing, robotics, drones, gene editing, nanotechnology and solar PV.

- Lall S. (1992) Technological capabilities and industrialization. World Development. 20(2):165–186.

- For a survey of this literature, see Freire C. (2021) Economic complexity perspectives on structural change. In Foster-McGregor N, Alcorta L, Szirmai A and Verspagen B, (Eds). New Perspectives on Structural Change: Causes and Consequences of Structural Change in the Global Economy. Oxford University Press. Oxford:188–215.

- ITU. (2020) Measuring digital development - Facts and figures 20120. International Telecommunication Union, Geneva.