View all episodes on our Tell Me How: The Infrastructure Podcast Series homepage

In the first part of our final episode, the host Roumeen Islam, revisits some of our guests' key insights. We focus on digital technologies and markets, addressing the digital divide and building effective cybersecurity as well as the energy transition, specifically financing the transition, drivers of the renewables market, and managing economic and social impacts.

Listen to this episode on your favorite platforms: Amazon Music, Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Podbean, and Spotify

Transcript:

Roumeen Islam: This is the World Bank’s Infrastructure podcast, and I'm the host Roumeen Islam. Today you will hear the first part of our concluding episode for the Tell Me How series. In this series, we covered important topics in a number of areas. For example, we talked about digital technologies and markets, the energy transition, climate and crises, transport and development, public-private partnerships in infrastructure. And running through all these topics was a very important underlying theme, innovation for economic progress. I wanted to revisit some key insights from our guests.

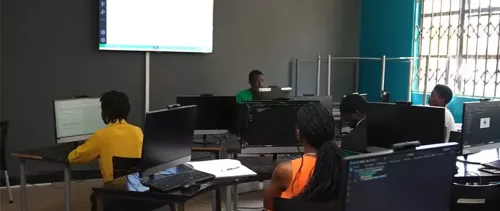

Let's start by taking digital technology. Three important areas we dealt with are: digital divide, cybersecurity and competition policy. One of the items we discussed inequality in digital access and usage continues to be a concern in all economies, but particularly in poorer ones. The good news is that there are continuous innovations that lower prices for users. And there's also a lot that policy can do to increase access and usage. Key elements being a supportive regulatory framework for private investors, promoting competition in the telecommunications sector and in related markets and making sure that there is a mechanism for funding, the poorest users. Let's hear our expert, Tim Kelly on this topic.

Tim Kelly: Now you need both physical investments in new productive network infrastructure, but you also need regulatory changes. And one tends to follow the other and our experiences are that regulatory constraints may be preventing the expansion of the network and access to the existing networks. And in some countries, in some cases, companies are making large profits on services that rely on high-speed networks, but not necessarily reinvesting those profits in new telecom infrastructure.

Roumeen Islam: We also discussed the state of cybersecurity, which depends on market dynamics as well as on public policy. Regulatory frameworks and national guidelines that support transparency, standards for information disclosure and sharing, and those that assign responsibility, allocate losses in case of attacks or breaches in security are very important in determining how much cybersecurity there is in markets, Professor Tyler Moore explains.

Tyler Moore: The good news is that we've identified some market failure. Information asymmetries and externalities, and this motivates the need for a policy intervention to try to correct for them and there are a few standard approaches you might try, and many of them can be put into two buckets.

You have ex-ante safety regulation and ex-post liability. So ex-ante safety regulation is used whenever the harm is potentially so great that you want to prevent it from happening in the first place. You don't want your electrical grid to be taken down by an attacker. So, you can impose some rules that would mandate some level of security investment to fix a problem.

Roumeen Islam: But a world where innovative digital technologies are everywhere needs a new kind of well-informed management that customizes cybersecurity measures to their firm's particular needs, where leaders understand the potential holes in their systems and the consequences of inaction, and they take action to support innovative cybersecurity measures. Expert Neil Daswani explains why this is important.

Neil Daswani: I think we live in a world today where a lot of organizations primarily work to comply with a whole bunch of these security compliance standards. But the problem is that the overwhelming majority of organizations that have been breached were compliant. The compliance involves checking hundreds of checkboxes, satisfying minimal criteria for all of them, and has not necessarily helped in preventing all of these breaches.

Roumeen Islam: Market actors, such as cyber insurance firms can help promote tighter cybersecurity. Especially through innovative business models that help manage risk, especially for smaller uncorrelated attacks, not systematically important ones. Let's hear expert Daniel Woods:

Daniel Woods: One aspect of that I believe should be celebrated and that is how cyber insurance has created these incident response teams who are engaged by a hotline that's manned 24 7. And in particular, we should see this as insurance setting up, essentially this fire brigade of cybersecurity, but still there's a lot of work to be done.

Roumeen Islam: Still on digital technologies, we considered whether big tech was so big that it was stifling competition and innovation. Where the merger and acquisition policy could be designed to better protect newcomers and the welfare of consumers and society. We learned how difficult it is to make relevant determinations, such as the size of the relevant market, the potential innovation lost, the distribution of profits and how important it is to have regulatory cooperation across borders by learning from others' experiences. For example, with respect to app purchases, taxes and revenues on ads, third party restrictions and the use of platforms and data usage among others. In this regard, Professor Michael Katz says the.

Michael Katz: How strongly do the merging firms compete with one another? What does the evidence say? What does the evidence tell us about whether there are other firms that they would continue to compete with, after the merger? So get less hung up on how do we put things in this market definition box of inner out. You know, when you do merger analysis, it's largely a predictive exercise. You're asking yourself if the firms are allowed to merge, what will happen and how does that compare with what would happen if they're not allowed to merge.

Roumeen Islam: In episodes covering the energy transition. We had some rather exciting sessions dealing with renewable energy technology policies and financing to support their adoption. And on the other side, managing the transition, we even had a session about valuing renewable energy assets in national wealth. We first handled innovation in battery technology. Battery storage capacity is critical to advance the use of renewable energy whose production is variable, battery store energy, essentially electricity. And we use it everywhere in machines and cars and homes. Costs have been falling, technology has been improving but much more progress is needed on both fronts. We also discussed how policy and regulatory frameworks need to be put in place to legally enable their use to integrate and maximize battery use in our electricity systems today, let's hear from our expert, Chandra Govindarajalu on this:

Chandra Govindarajalu: That's because wind and solar power output is variable and uncertain, as one can imagine. For example, I'll put up solar PV changes in seconds when a cloud passes by. Wind also changes its power and direction. So, that's the issue. And for example, if no regulations explicitly state that battery storage can provide good services, utilities may be unwilling to procure services from a battery storage provider or a system.

Roumeen Islam: Secondary, there are a number of metals and minerals such as lithium cobalt, or nickel that are needed for batteries, but which are mined only in a handful of countries. The markets for these precious elements are being affected not only by rising demand for green energy but also they're boosted by policy and changing consumer preferences. And also by volatility in fossil fuel markets. And while revenues from mining could be used to support livelihoods in poor countries, improper practices can worsen environmental and social problems or intensify the search for substitutes. Policies to manage these are needed If countries wish to maximize revenue potential. Interestingly rising insecurity in fossil fuel markets is highlighting potential risks in critical mineral sectors too let's hear expert Chris Sheldon on this topic.

Chris Sheldon: And one thing is very important, as the demand for the minerals really takes off and the countries, they really need to manage their revenues. They're exchanging essentially an asset in the ground and natural asset for cash for a financial asset, but eventually, those resources are going to run out. Now the first step in managing an asset is of course knowing how much you have.

Roumeen Islam: And now let's hear our expert Daniele La Porta.

Daniele La Porta: Even if we scale up recycling rates for minerals like copper and aluminum, by a hundred percent recycling and reuse would still not be enough to meet the demand for renewable energy.

Roumeen Islam: Renewable energy technologies offer the potential of cheap energy in the future. After all sunshine is free. So, on a recurring basis, over the longer term, you can imagine that this is cheaper than paying for oil and gas or coal. Yet, like the case with commercialization of most human technologies upfront investments have to be made to allow their use to change systems as needed. Think of charging stations, think of building solar plants and wind turbines. All this requires finance. The timing of costs and benefits is a hurdle to the transfer of technology. Another hurdle is that there's always a certain amount of risk related to investments and technology in new areas or in new countries. Policy and reforms can help manage both risks and raise incentives for investment in technology. For poorer countries, external support will facilitate the transition. Let's hear expert Demetrios Papathanasiou on this.

Demetrios Papathanasiou: It's a huge challenge, but there is also still a huge economic opportunity. You do have people that even today are willing to pay quite a bit for basic electricity services and for rather small quantities of electricity services. Now, the question is, can this be delivered otherwise? And the answer is yes. Today you can easily install a small grid with solar panels, battery bank, and this can serve a whole village.

Roumeen Islam: And renewable energy resources can add to a country's wealth too. Let's hear from expert Grzegorz Peszko.

Grzegorz Peszko: So by the same token, the renewable energy can be treated as economic asset, Only when they are generating the flow of economic rent under current markets and physical conditions. So, for instance, a remote river with no hydro-power generation facilities on it is not an asset. It's not a renewable energy asset. The two key findings were that, first of all, The value of the asset is major, is large. So, what we found out is that in the last few years, in these 15 countries, the value of hydro-power wealth range between $1 and $4 trillion on an annual basis. And a second, what we found out by the size of this range that these values have been quite volatile.

Roumeen Islam: So, what about managing the transition. For example, moving away from coal and fossil fuels. Well, this means restructuring entire segments of economies with social and political repercussions. It means ending subsidies for fossil fuels, adhering to the notion of a just transition that explicitly takes social impact into account, are key to moving ahead.

Should governments invest in the future or help disengage from the past. Both it turns out so innovative ways of restructuring and repurposing assets, bringing in new investors, and retraining and supporting labor are key elements of this transition. Listen to expert Chris Sheldon on this.

Chris Sheldon: Yeah, that's really the most central question. And there's more than one set of people affected. Obviously, there are the workers who’re directly impacted by closure, but there are also other community members in the region that get affected. The workers typically receive early retirement If they're close to retirement or packages to support them for retraining or developing new skills for new jobs some even starting new business ventures.

Roumeen Islam: And still on this topic a tax on fossil fuels or a carbon tax is an important policy measure to support the energy transition. The carbon tax is used to shift economic activities towards lower energy intensity or clean energy use. This restructuring has differing distributional impacts across countries and between rich and poor people within countries, the latter of whom may lack access to energy or operate in informal markets. To support an equitable transition each country will need policies tailored to their particular circumstances. Listen to professor Jan Steckel, as he explains this.

Jan Steckel: I think for designing a successful reform, it's important to go beyond the standard economist toolbox. So, we often prefer to make a lump and transfer the same amount to everybody. However, categories might have institutional difficulties to set this up, how to transfer the money, and how to reach the people in need. Therefore, we increasingly also think of using the existing targeting mechanism.

Roumeen Islam: So, let me end here for the first part of our final episode, and don't forget to tune in next week for the second part. Thank you and bye for now.