This post is part of the series UN 2.0 and the Metaverse: Are We Seeing What Is Possible?

- Part 1: Harnessing technology, driving SDGs

- Part 2: ‘CitiVerse: Turning the world into a global village (or rather sandbox?)’

- Part 3: ‘Readiness across the spectrum: Countries’

- Part 4: SDGs as ethical, human rights-based, and technological boundaries of the metaverse

In our UN 2.0 and the Metaverse blog series, we have explored the potential of digital convergence to accelerate the sustainable development goals (SDGs). However, as we delve deeper into the immersive realm of the metaverse, Part 4 confronts a critical question: Are the SDGs merely use cases, or do they represent something more profound?

We will analyse how the SDGs can serve as essential boundaries – ethical, human rights-based, and technological – to guide the metaverse’s evolution. The Global Digital Compact is the UN’s vital framework for steering humanity towards a sustainable future.

Ultimately, could UN 2.0 provide the solution needed to tackle the challenge of timing tech governance?

A. Recap of Parts 1 to 3

To understand the relevance of such boundaries, let us briefly recap the landscape we mapped out in the initial parts of this series. In Parts 1 to 3, we explored the converging visions of UN 2.0 and the Global Initiative on Virtual Worlds and AI – Discovering the CitiVerse. We examined frameworks such as the Economist Impact’s Inclusive Metaverse Index and U4SSC’s Dynamic Policy Model, which aim to guide this profound transformation.

Furthermore, we discussed the role of humans in this socio-technological shift and how to balance technology with human agency. The Quintet of Change framework addresses this balance by promoting human capacity-building. It acknowledges that technological advancement is neither linear nor one-directional, as both technology and humans co-evolve in complex ways.

B. Back to the future with Agenda 2030

For this article, we return to Agenda 2030 and how the UN envisioned a positive future through the SDGs.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all UN member states in 2015, provides a comprehensive framework for global peace and prosperity. At its core are the 17 SDGs, a shared vision calling for immediate action through collaborative global partnerships.

The SDGs are more than just a roadmap for sustainability; they act as drivers of change, shaping policies, innovation, and governance structures. However, we are now exploring visionary concepts like the metaverse precisely because we have fallen behind on Agenda 2030. In other words, we are still grappling with persistent challenges that resist change.

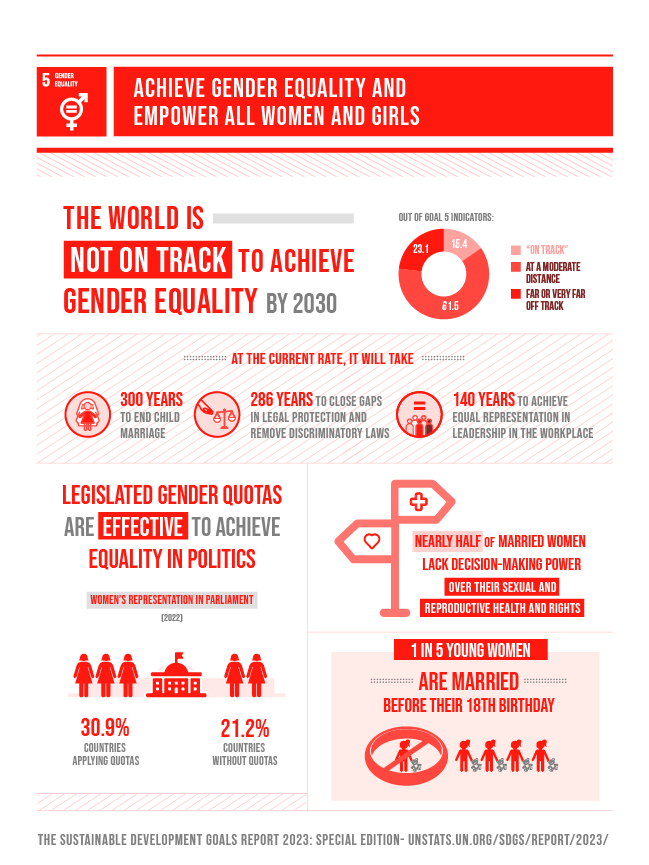

1. The systemic problem behind SDG 5

For example, it will still take 300 years to end child marriage and 286 years to close gender gaps in legal protection. Gender equality (Goal 5) is a systemic challenge across nations and time – one that is clearly resistant to change. Gender inequality is not just a policy problem but an issue deeply embedded in social structures, economic systems, and cultural norms.

Metaverse technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, offer new ways to raise awareness of the need for change. When it comes to gender equality, stepping into another person’s virtual skin is a far more impactful experience than watching a documentary or reading a report. Providing services that would otherwise be out of reach can help reduce disadvantages. These include essential services such as medical advice, education for girls, governmental services, and even access to justice.

Achieving Gender Equality – SDG 5

2. From race to socio-technical unity

While immersive metaverse experiences can be utilised to raise awareness, they can also be abused. Digital technologies enable the unprecedented scaling of abusive experiences if not appropriately guided. The underlying problem is not new: when should we regulate technology without hindering its positive potential?

This issue is known as the Collingridge Dilemma. Articulated in the 1980s, it highlights that technology control is a race against time. Influence is easiest to exert in the early stages of development when we understand the technology’s implications least. However, by the time we grasp the full societal consequences, control becomes significantly more complex.

UN 2.0, through the Pact for the Future and the Global Initiative on Virtual Worlds, addresses this dilemma by consciously integrating technology into the fabric of reality rather than passively observing its development. UN 2.0 embodies a multistakeholder approach, bringing technology developers and the private sector into a collaborative framework. This shared vision aims to replace a competitive race with a unified effort – one focused ongoverning technology’s implications as they emerge. The U4SSC’s Dynamic Policy Maturity Benchmark Model is an example of such an approach (see Part 2).

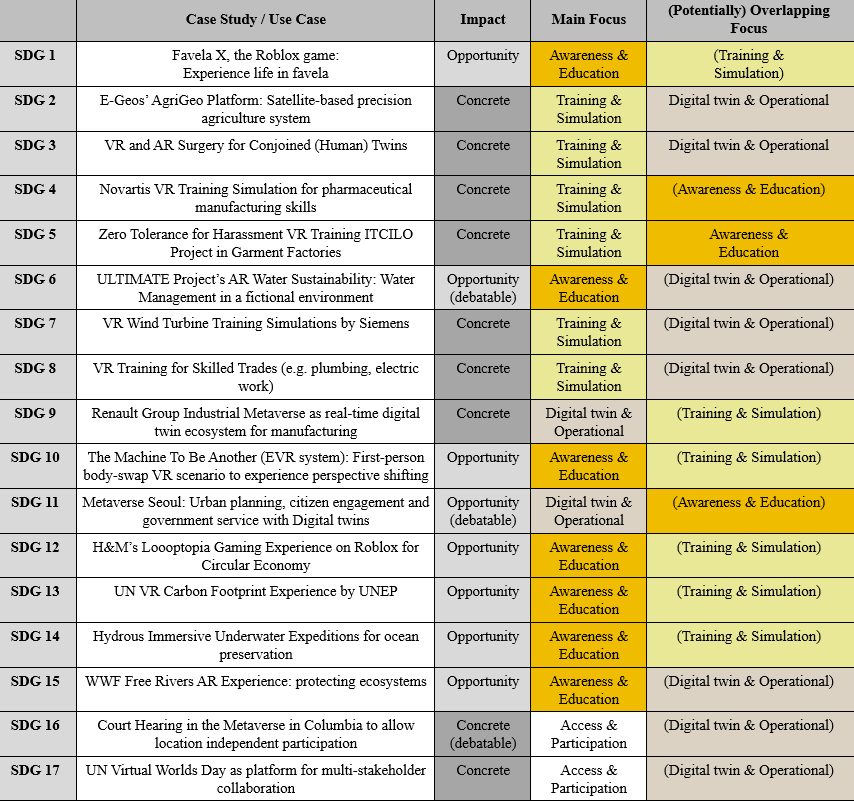

3. Case studies: Real impact or opportunity

Let’s examine some case studies. A key outcome of the Global Initiative is the UN Executive Briefing on Unlocking the Potential of Virtual Worlds and the Metaverse for the Sustainable Development Goals, which features case studies from stakeholders and UN organisations, illustrating opportunities, challenges, and tangible impacts. Rather than repeating the case studies, the following table provides an analytical overview of how metaverse technologies contribute to each SDG.

Analytical overview of how metaverse technologies contribute to each SDG

Such a simple visualisation reveals a pattern between the focus area and the impact. It reflects the well-known challenge of measuring the immediate effects of awareness and education. However, once an initiative shifts towards training and simulation or digital twins, its impact becomes more measurable and concrete. Case studies marked as ‘debatable’ highlight the difficulty of directly measuring their short-term impact on SDG targets, despite their value for awareness and engagement.

This pattern underscores a key point: to achieve concrete impact aligned with the SDGs, metaverse initiatives must go beyond awareness and education, moving towards more measurable applications such as digital twins. Technology enables us to analyse complexities, identify challenges, and uncover opportunities. However, these tools are only as effective as the ethical and legal boundaries that govern them.

4. Shaping the metaverse

Shaping the metaverse is not an easy task, especially as it remains a concept. As a concept, it represents an idea of how such an integrative ecosystem of virtual worlds could develop. The visualisation at the beginning of the Executive Briefing symbolises the current stage of development. It depicts the metaverse as a relatively young plant that requires nurturing to grow into the envisioned sustainable ecosystem.

The uncertainty and shapelessness of the metaverse make it difficult to ensure adequate forward-looking regulation. However, while we might not be able to foresee the shape of the ecosystem itself, the underlying technologies are already embedded in our socio-technical system – pushing boundaries, particularly through the internet, social media platforms, and, most prominently, AI.

The question is: what boundaries are being pushed? Are they merely technical constraints, or do they extend to legal and human boundaries?

5. The issue of integrity

An acute example is deepfakes. A deepfake is a manipulated or synthetic audio or visual medium that has been convincingly altered to misrepresent a person and deceive the media consumer. In a deepfake, the person appears to be doing or saying something that they did not actually do or say.

Deepfakes are not a new phenomenon; they have been around for some time.

A striking example is Nobel laureate Albert Einstein, who has been resurrected multiple times. We can find him as a humanoid robot, a digital twin, and a digital human. In some cases, his resurrection is seen as a celebration of his legacy (as by ETH). In others, he serves as a promotional ambassador (e.g. for Smart Meters) or as a form of entertainment (Daily Mail). A deepfake is created when his legacy is mixed with external input – that is, when he is made to do or say something he never actually did.

6. The human at the centre: Purpose or target

Deepfakes are not only used to resurrect the dead and immortalise their legacy. A 2019 study found that between 90% and 95% of all deepfakes involve non-consensual pornography, with 90% targeting women. This constitutes a massive violation of personal and social integrity, even leading to suicide as a consequence of the humiliation and reputational damage caused by such deepfakes (Teenage girl’s suicide, 2022) and sextortion (FBI, 2024).

If pictures and videos alone can have such an impact, what will happen when we can literally step into someone else’s skin? The metaverse represents a more immersive form of communication – a digital convergence with the physical (biological) world, forming a new ecosystem.

What boundaries are deepfakes pushing? Are they merely expanding the limits of what is technologically possible, or are they encroaching on the very boundaries that make human social life possible?

Cascading effects of three types of deepfakes (a manipulated pornographic video, manipulated audio evidence and a false political statement) on the individual, organisational and societal level (European Parliament).

7. The role of the Global Digital Compact for SDGs

The troubling examples of deepfakes and their severe consequences, such as reputational damage and mental health crises, highlight the urgent need for frameworks to address these challenges effectively. The Global Digital Compact (GDC), as part of UN 2.0, is one such framework designed to guide digital transformation and foster international cooperation towards a better future for all.

At its core, the GDC establishes clear boundaries that prioritise inclusivity, sustainability, human rights, and ethical considerations within the rapidly evolving digital landscape. Despite its non-binding nature, the agreement updates the social contract by acknowledging the role of digital technology and the responsibility of all stakeholders.

Here’s how the GDC and SDGs can contribute to mitigating the risks associated with deepfakes and similar digital threats:

- Promotion of human rights: The GDC emphasises the importance of protecting human rights in the digital space. This includes safeguarding individuals from harm caused by malicious digital content, such as deepfakes. By advocating for a safe and secure digital environment, the GDC aligns with SDG 16, which aims to promote peaceful and inclusive societies and provide access to justice for all.

- Digital literacy and awareness: The GDC calls for enhanced digital literacy and education initiatives. By empowering individuals, especially young users, with the skills to critically assess digital content, they can better navigate challenges like deepfakes. This supports SDG 4, which focuses on ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all.

- Data governance and accountability: The GDC advocates for responsible data governance, which is crucial in combating the misuse of technology for creating harmful content. By establishing clear standards and accountability measures for digital platforms, the GDC can help prevent the spread of deepfakes and protect individuals’ rights. This aligns with SDG 16, which calls for effective, accountable, and transparent institutions at all levels.

- International cooperation: The GDC recognises that addressing issues such as deepfakes requires international collaboration. By fostering partnerships among governments, tech companies, and civil society, the Compact can facilitate the sharing of best practices and resources to combat digital threats. This is essential for achieving SDG 17, which emphasises the need for partnerships to achieve the goals.

- Support for mental health initiatives: The GDC can also play a role in promoting mental health awareness and support systems for individuals affected by online harassment and deepfakes. This aligns with SDG 3, which aims to ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

In summary, the GDC and the SDGs provide a framework for addressing the multifaceted challenges posed by deepfakes and other digital threats. By promoting human rights, enhancing digital literacy, ensuring data accountability, and fostering international cooperation beyond governments, the framework also calls for action from the private sector.

C. Conclusion of Part 4

In this part, we have demonstrated that the SDGs are not merely aspirations for the metaverse; they can serve as essential boundaries for its responsible and sustainable evolution – a necessity that becomes even more critical when considering the profoundly immersive nature of this digital realm. Beyond serving as use cases, the SDGs provide the ethical, human rights-based, and technological limits within which this new socio-technical ecosystem must develop.

Treating the SDGs as these fundamental boundaries ensures that metaverse technologies, despite their immense power – from virtual reality to digital twins – serve broader societal aspirations. They become tools for protecting human dignity, fostering inclusivity, and actively mitigating systemic inequalities rather than exacerbating existing harms or creating new ones.

The GDC is the crucial framework for implementing these boundaries in this immersive digital space. It acts as a socio-technical contract, cohesively integrating human rights, digital literacy, data governance, and international cooperation among all stakeholders to guide a positive and responsible digital evolution – even in the face of unknown risks, risks that may be heightened by immersive experiences.

The power of the Global Initiative on Virtual Worlds and AI – Discovering the CitiVerse lies in its proactive approach. Defining SDG-aligned boundaries positions the metaverse as nothing less than a gigantic exercise in foresight. This helps us anticipate and address risks before they fully emerge. Just because risks are unknown does not mean they cannot yet be understood. The metaverse, guided by these boundaries, allows us to identify them in outline, even in its most immersive and potentially transformative forms. As part of UN 2.0, it is an effort to overcome the race against time between technology and its regulation.

D. Next up: What’s wrong with legal?

Blaming, shaming, and the looming threat of technological disruption are frequently directed at the legal world. Its reputation is constantly challenged by claims of inefficiency, falling behind technological progress, or, even worse, slowing it down. Justicia seems out of balance, and public trust in her is eroding.

In Part 5, we will examine the known risks and core challenges facing the legal world. Additionally, we will reframe the Collingridge Dilemma and explore how confidence can be rebuilt in the digital space.

E. Ask Diplo’s AI Assistant

Curious to explore the 52 technical reports by the Focus Group Metaverse and other relevant documents? We have developed a dedicated DiploAI Assistant for UN Virtual Worlds to make research more accessible for our readers. If you have any questions, simply ask the DiploAI Assistant.