Introduction

The South Centre organized a webinar in collaboration with the Global Alliance for Tax Justice on 15th June 2021 to address key issues for developing countries in negotiations on the taxation of the digital economy.[1] The webinar was aimed primarily at delegates from the Group of 77 (G77) and China in Geneva, tax officials from the Global South and civil society. The objective of the webinar was to enable constructive discussions among developing countries on the key issues in the tax challenges of the digital economy, as it is even more crucial for them to raise revenue at this juncture of the pandemic. The panellists were composed of two Steering Group Members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Inclusive Framework, hailing from Africa and Latin America, an Asian member of the United Nations (UN) Tax Committee and three members from civil society. Abdul Muheet Chowdhary, Senior Programme Officer of the South Centre Tax Initiative moderated the discussion. The webinar recording can be accessed here.

The webinar covered the following topics:

- Source and residence countries in global profit allocation: where will tax be paid, who will pay and how to deal with remote sales? Shifting goalposts on thresholds and the possibility of a deemed routine return for a remote nexus;

- What would be the Pillar One Blueprint’s level of re-allocable profits and what will be redistributed to market jurisdictions? Questions of profitability and allocation ratios;

- Who gets the first claim on undertaxed income? Rule order under Pillar Two and the Subject to Tax Rule;

- ‘Certainty’ of arbitration? Dispute resolution in Amount A. What would the ‘binding, non-optional dispute prevention and

- Are alternatives available? Exploring the UN’s solution on taxing Automated Digital Services;

- Why transparency and institutional legitimacy matters in international rule making and norm setting.

Prof. Carlos Correa, Executive Director of the South Centre, acknowledged the collaboration with the Global Alliance for Tax Justice, and welcomed the participants. In his remarks, he observed that this meeting is particularly timely for two main reasons:

a) the Group of Seven (G7) ministers of finance have announced an agreement to set a minimum global tax of 15 percent (which is lower than the original rate proposed by the US administration). This decision was taken without the participation of many of the developing country members and outside the United Nations, and

b) the 139 member countries of the OECD Inclusive Framework (IF) had decided to hold negotiations to provide a solution to the taxation of the digitalized economy by July 2021, and no later than October 2021. As the deadline for a solution draws near, it is important for developing countries to organize themselves and to discuss the key issues for developing countries, including possible common elements and ‘red lines’ in this negotiation.

He also emphasized that getting a right outcome on taxation is crucial to face the current devastating situation of COVID-19, and the critical need for countries’ taxation rights to be recognized, as the digitalization of the economy has meant that companies no longer need to be physically present in countries to generate profits, thereby creating a new set of challenges for the existing international tax rules.

Dr. Dereje Alemayehu, Executive Coordinator of the Global Alliance for Tax Justice, expressed his concern that a mandatory and non-optional dispute resolution system and a curb on unilateral measures would be part of the developed countries’ strategy to lock developing countries into an agreement which will bring significant benefits in the short term but will continue to deprive them in the long run of taxing rights on part of the profits generated in their economies.

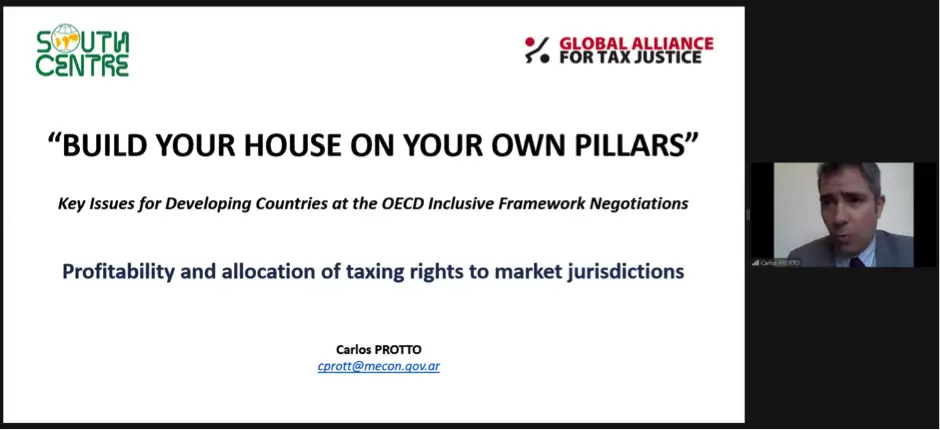

Carlos Protto, member of the Steering Group of the Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) for Argentina and member of the UN Committee of Experts on International Cooperation in Tax Matters, made a presentation[2] entitled ‘What will be redistributed to market jurisdictions? Questions of profitability and allocation ratios’.

Mr. Protto explained that the current international tax rules depend on a physical presence threshold for countries to tax profits earned by foreign entities in their jurisdictions. Remote market penetration exculpates Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) from having to pay taxes from their operations. Pillar 1 is a global solution which seeks to address issues posed by both digitalization and globalization through the reallocation of taxes under its ‘Amount A’.

Amount A taxes in-scope MNEs in market jurisdictions on a portion of their global profits which is deemed to be over and above what would normally be earned in relation to functions performed, assets employed, and risks assumed in the provision of the business activities.

To determine excess profits, a fixed profitability margin will be used to simplify the calculations. The G7 have proposed 10% of Gross Revenue and this threshold is expected to be confirmed by the Inclusive Framework. On the other hand, developing countries favor a lower profitability ratio to increase the tax base.

A portion of the excess profits is then reallocated to tax in market jurisdictions based on a predetermined allocation percentage that is yet to be decided. Developing countries favor a higher percentage (30% - 50%) to contribute towards more resource mobilization whereas the G7 are satisfied with a minimum of 20%.

Who gets a share in the portion of the excess profits?

A country must first demonstrate that it meets a nexus requirement based on revenues per annum. MNEs should generate at least EUR 1m, a figure which must still be agreed. Developing countries will be allowed a lower threshold of EUR 250,000 to trigger the nexus requirement.[3] A share of tax revenue in the portion of excess profits is expressed as a ratio of sales revenue in a particular country to global sales revenue.

Views expressed by developing countries

To increase the tax base and to provide equitable tax treatment, developing countries favor:

- A lower threshold of global revenue per annum is proposed to increase in-scope MNEs subject to Amount A. The current proposal is somewhere around EUR20bn, but this was initially set at EUR750m in the Blueprint;

- re-allocable percentage should apply on global profits instead of excess profits and this is more in line with Article 12B under the UN Model Tax Convention (MTC);

- a low profitability ratio to determine routine profits;

- a high reallocation percentage of the non-routine profits;

- a low threshold of gross revenues from a market jurisdiction to trigger the nexus.

Sol Picciotto, Coordinator of the BEPS Monitoring Group, spoke about rule order in Pillar Two and the importance of the Subject to Tax rule. He began by highlighting that digitalization was only part of the wider challenge posed by globalization which started in the 1970s with the dematerialization of economic activities, which was already manifested by a shift to the services economy. Seen now is the digitalization of services and that already with the shift to services and internationalization of services, many of these problems were already experienced, particularly by lower income countries which have been primarily importers of services. Only now are the more developed countries experiencing the same problem, and the world is finally reaching some kind of a turning point where there is a proposal to consider multinational corporations on the basis that they are single firms.

Sol Picciotto, Coordinator of the BEPS Monitoring Group, spoke about rule order in Pillar Two and the importance of the Subject to Tax rule. He began by highlighting that digitalization was only part of the wider challenge posed by globalization which started in the 1970s with the dematerialization of economic activities, which was already manifested by a shift to the services economy. Seen now is the digitalization of services and that already with the shift to services and internationalization of services, many of these problems were already experienced, particularly by lower income countries which have been primarily importers of services. Only now are the more developed countries experiencing the same problem, and the world is finally reaching some kind of a turning point where there is a proposal to consider multinational corporations on the basis that they are single firms.

Pillar 1 focuses on allocating global profits which is a step forward but obviously in a rather limited way. The African Tax Administration (ATAF) group has proposed a much better and simpler approach on allocating total profit rather than separating it into routine and non-routine.

Pillar 2 aims to address the “race to the bottom” by trying to have stronger international coordination on the taxation of under-taxed profits. The design has some fundamental flaws which have been highlighted by comments, particularly from lower income countries because they are most aware of the problem, and the proposals they put forward, as the Group of Twenty-four (G24)’s proposals point out, are actually in the interests of all countries.

The G24 proposal to re-balance the allocation of tax rights in Pillar 2 would benefit all countries. The major flaw in the existing Pillar 2 Blueprint is the imbalance of taxation rights that it proposes. The central element of Pillar 2 is the so-called GloBE, which has two elements: it has a right for home countries of multinationals to tax under-taxed profits and it has a right for source countries where activities take place to tax under-taxed profits.

However, Pillar 2 as it stands currently proposes to give priority to the home country, which is an extension of rules which already exist in many countries as the rules on Controlled Foreign Corporations (CFC). The country of residence of the parent company of a multinational deems its worldwide profits as attributable to the shareholders of the parent company and applies tax to those profits. Normally CFC rules are limited to passive income and to income declared in low tax jurisdictions defined in various ways, but the other important element of CFC rules is that they give a credit to source country taxes. So CFC rules have the advantage that they do give source countries the primary right.

Nevertheless, what is proposed in Pillar 2 is to give priority to the home country through the income inclusion rule and so the priority rule would be the jurisdiction of the ultimate parent. If the ultimate parent jurisdiction, which are mostly the major developed countries like US, Japan, Germany, etc., for whatever reason refuses to exercise its taxing rights, then the next “turn” to apply the income inclusion rule would go to an intermediate parent company. Only if neither of those jurisdictions applies the income inclusion rule, could a source country apply what is called the under-taxed payments rule.

Lower income countries, both through the G24 and through the ATAF, have essentially said that this is not acceptable. The Pillar 2 blueprint does propose a third rule, the so-called subject to tax rule, but this would require changes to tax treaties. What now seems to be envisaged is to go ahead quickly with the GlobE with its two components: the income inclusion rule and the under-tax payment rule and then maybe introduce the subject to tax rule when tax treaties can be changed. The G24 rightly said this is not acceptable and source country taxation, maybe through the subject to tax rule, should be an integral part.

There has been a lot of discussion about the minimum effective tax rate. The talk about having it as low as 12.5% is gone. The G7 has said that the minimum should be at least 15%, but a higher rate should be envisaged. But probably as important, if not more important, is the applicable rule because the issue is who gets the right to tax these under-taxed profits. Now a group of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have put forward a minimum effective tax rate (METR) proposal[4] which would resolve the problem, remodelling the GloBE and allocating, on a formulaic basis, the right to tax the undertaxed profit. So, it would use the same building blocks in the Pillar 2 blueprint for defining the effective tax rate and identifying the undertaxed profits. But instead of a top-up tax, it would allocate the undertaxed profits on a formulaic basis to countries based on where the multinational has real activities. This is familiar to national tax systems in federal countries like the USA; the so-called three-part formula has also been proposed within the European Union (EU). So, it would be a formulaic approach to reallocate the right to tax undertaxed profits according to whether each company has sales, assets, and employees. That would be a balanced allocation of the taxing right; maybe the Inclusive Framework would adopt that proposal as it stands, but in any case, clearly a better solution needs to be found for the priority issue.

If not, then there is no reason why countries that are primarily source countries should join in the Pillar 2 proposal. There is no way in which they can be required to give priority to the income inclusion rule, and they should not do so. There are other mechanisms that they could develop either on a purely unilateral basis, but preferably jointly, and they could already build on other measures for defending the source tax base. They could introduce alternative minimum taxes. They could defend the source tax base by applying the principal purpose test to deny deductions for payments that go to a conduit located in low tax jurisdictions if the motive is primarily tax avoidance.

So there are many ways in which source countries could protect their tax base. Unless the proposals that have come from G24 and others for a balanced allocation of taxing rights under Pillar 2 are accepted, there would be no reason to join in a Pillar 2 which gives priority to home country taxation of undertaxed profits, which even goes beyond existing CFC rules. It could only be enforced on countries if they accepted that restriction and there is no reason why they should accept that.

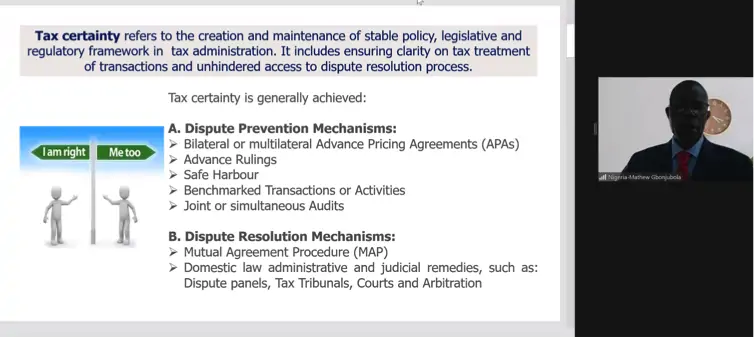

Matthew Gbonjubola, Nigeria’s representative in the Steering Group of the Inclusive Framework, presented on dispute resolution under Pillar 1. He began by stating that tax certainty meant creating and maintaining a very stable policy, legislative and regulatory framework in tax administration with the objective of ensuring clarity of tax rules and also ensuring that taxpayers have access to a dispute resolution framework.

Traditionally, countries use dispute prevention mechanisms which include bilateral or multilateral Advanced Pricing Agreements (APAs), advance rulings, safe harbors, benchmarked transactions or activities, and joint or simultaneous audits. As for dispute resolution mechanisms, there are Mutual Agreed Procedures (MAPs) under treaties and domestic laws and judicial remedies such as dispute panels, tax tribunals, courts and arbitration.

Pillar 1, particularly Amount A, seeks to shift to a multilateral arrangement, particularly to secure the determination and allocation of Amount A which is based on a formulary approach and then to also avoid disputes in the areas relating to marketing and distribution, and all other cases that may be linked with Amount A. The architecture of the proposed tax certainty mechanism or dispute resolution mechanism for Pillar 1 are broken into two: one for Amount A which will deal with issues of dispute prevention and dispute resolution and then, for issues beyond Amount A, will dwell mainly on dispute resolution.

Regarding the possible disputes that may arise as regards Amount A, Mr. Gbonjubola specified five possible areas:

(1) Whether or not the MNE is in scope. The threshold will address that but there are issues around segmentation.

(2) Type of business in scope. Before now, there was the segregation between Automated Digital Services (ADS) and consumer-facing business. The US proposal has merged that together but there are also issues of carve-outs relating to agriculture and financial services, and uncertainty about these could create disputes.

(3) Allocation of costs. This covers particularly joint costs and losses to be carried forward.

(4) Existence of tax nexus. Amount of in-country turnover and disputes if there are differences between the in-country nexus for different countries.

(5) Identification of relieving or paying entities.

Amount A Tax Certainty Design

Amount A is broken down into two: one is the Early Tax Certainty Process which is mainly a dispute prevention mechanism wherein there is a review panel and a determination panel that are going to be set up under the multilateral agreement. The latter part of it is where there are disputes and the proposal is then to have a mandatory binding mechanism where pronouncement of the arbitration will be binding on the relevant jurisdictions which form part of the Inclusive Framework.

Three Components of the Early Tax Certainty Process

A – Scope

- Determine whether an MNE group is within the scope of Amount A

- Determine whether an MNE group’s determination and allocation of Amount A is agreeable

- Confirm paying and relieving entities.

B – Review Panel

This would consist of members of 7 developed economies and 1 developing economy who will review the tax returns of MNEs. In case of disputes, a position paper is submitted.

C – Determination Panel

Members of 6 developed economies and 3 developing economies will determine disputes arising based on the position paper provided by the review panel. A decision of the determination panel will be binding on MNEs if it is an Inclusive Framework member.

Mandatory Dispute Resolution

It is going to be mandatory for all Inclusive Framework members and the outcome is going to be binding on those members. However, the process is not yet fully defined and not fully agreed but it is expected it will be by way of arbitration. The scope and the objective would be to (i) ensure that transfer pricing adjustments do not create double taxation that are in scope of Amount A; and (ii) ensure that transfer pricing and permanent establishments-related disputes are resolved in a timely manner.

What are the concerns of developing countries?

Issue 1: Amount A determination and tax certainty

(i) Not adequate representation of developing countries on the various panels;

(ii) Non-consideration of carve-outs for developing countries which have no or very few MAP cases (suggestion was made by ATAF to carve these jurisdictions out);

(iii) Challenge that mandatory binding mechanism may not serve the interest of developing countries.

Issue 2: Tax Certainty beyond Amount A

(i) Concerns determination of transfer pricing issues linked to Amount A.

(ii) MAP cases may not be allowed to run their course, because parties may decide to use arbitration while the process for MAP is still not yet fully completed.

(iii) There are possible effects of what happens to national tax sovereignty where internal or domestic transfer pricing cases have to be taken to international arbitration.

Issue 3: Mandatory dispute mechanism

There are specific concerns in developing countries, mainly in African countries, which have constitutional limitations that will not enable them to submit the revenue of their government to arbitration in foreign jurisdictions. There is also concern on the fairness of the system and issue of expertise in arbitration process which is sometimes based on legislation of domestic countries. The cost of arbitration is also a major concern for developing countries such that the tax revenue may not warrant the cost, and the better option might be to forego the tax.

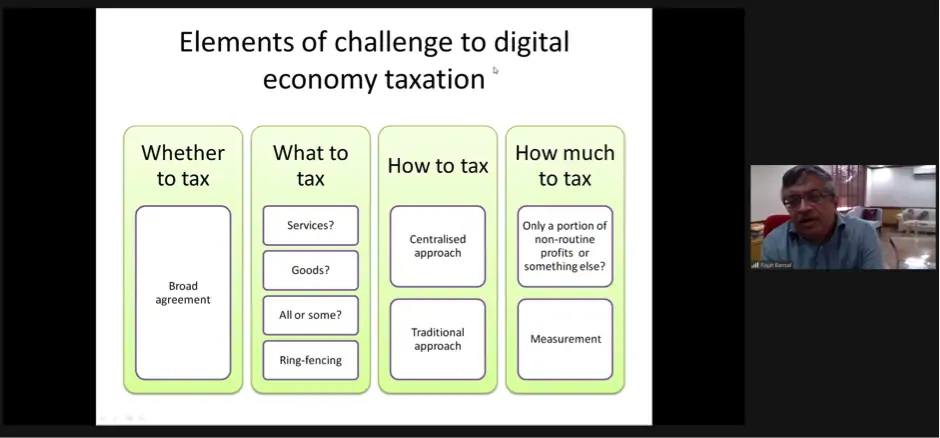

Rajat Bansal, Member of the UN Tax Committee (UNTC), started his presentation[5] on ‘Are Alternatives Available? Exploring the UN’s Solution on Taxing Automated Digital Services’ by providing a historical aperçu of the relationship between the digital economy and domestic resource mobilization. There are essentially four major issues which have been at the centre of the debate: Whether to tax? What to tax? How to tax?

Rajat Bansal, Member of the UN Tax Committee (UNTC), started his presentation[5] on ‘Are Alternatives Available? Exploring the UN’s Solution on Taxing Automated Digital Services’ by providing a historical aperçu of the relationship between the digital economy and domestic resource mobilization. There are essentially four major issues which have been at the centre of the debate: Whether to tax? What to tax? How to tax?

How much to tax?

Whether to tax?

Quite some time has been spent on this question but there is now consensus that the digital economy should be taxed.

What to tax?

Whether the tax should be on services rendered through digital means, internet or other digital networks or on goods, and if so which ones? There were also related issues of ring-fencing.

How to tax?

There are two possible approaches:

(1) Centralized Approach

Total profits of the MNE group will be pooled together and then they will be allocated to different countries subject to certain rules.

(2) Traditional Approach

Each country determines its share of revenue based on nexus of permanent establishment – can this approach be followed for the new challenge or not? This is the issue.

How much to tax?

The question is whether to tax only a portion of excess profits or something else.

The challenge relates to accurate measurement of the excess profits. It is not possible to measure this accurately in any manner when there are no accounts in the market jurisdiction specific to that jurisdiction. In such cases there must be an approximation. Both the OECD approach, as well as the UN approach, work by an approximation. It cannot be said that one is superior in the process of measurement because it would ultimately be the ease of measurement that would matter here and that should be kept in mind.

Why was an alternative approach needed?

Members in the UN Tax Committee felt there was a need for an alternative approach because of the complexity involved in the Two-Pillar Blueprints. Perhaps the most important reason was based on whether developing countries would be getting a reasonable share of tax revenue. Ultimately, any solution that is agreed would have a long shelf life. Tax treaties take years to change, and any international solution will be there for a time horizon of around 20 to 30 years.

Journey of Article 12B

Mr. Bansal then explained the journey of Article 12B and highlighted the UN Tax Committee’s composition, its work on Article 12B and its mandate to work for the interest of developing countries specifically.

Taxation of the digitalized economy was taken up as a workstream for the Committee when the present membership was constituted in the year 2017. The issue then was whether the UNTC should just observe what other forums were doing on the taxation of the digital economy or do something more. After that, due to a persistent push by some developing country members in the 18th session, a decision was taken that work will be done independently and not as mere observers.

A suggestion was made that there should be proposals from various members and to consider whether they could be adopted by the Committee or taken forward in the 20th session in June 2020.

There was a conference room paper, number 25[6], in which Mr. Bansal said he had submitted a proposal, in addition to one by Jose Troya from Ecuador. Those proposals were discussed and it was decided by the developing country members including Carlos Protto and several others that there was enough merit and enough reason for looking into the proposal submitted. A drafting group was formed to prepare a draft article for insertion in the UN Model Tax Convention. In the 21st session, the drafting group, of which Mr. Bansal and Carlos Protto were the coordinators put forward a draft of the article and its commentary.

It was discussed extensively amongst the members, continuously refined and at the 21st session of the Committee in October 2020 it was voted for in-principle approval for inclusion in the UN MTC. Thereafter, the refinement of the text and the commentary continued and in the 22nd session in April 2021 it was finally approved for insertion in the MTC.

Key features of article 12B

Article 12B provides an alternate approach for taxation of the digital economy in the UN model tax convention. Taxing rights flow through the domestic law and then there are bilateral tax treaties which override the domestic law. Treaties do not permit taxation if there is no permanent establishment. Treaties are negotiated all over the world based on two model conventions: the UN and the OECD. These have persuasive value on various countries across the world for negotiating bilateral tax treaties. If an article like 12B gets inserted into the UN model which is followed by developing and developed countries, then countries can probably adopt it into their treaties.

The scope of article 12B is automated digital services. The taxation under the article can be in two ways: the first is a gross basis withholding tax at a rate of 3-4% recommended in the commentary, which is a very reasonable rate. The second is a net basis option to give MNEs the option to declare their income on the basis of their actual profits. These ‘qualified profits’ can be computed based on the overall global profitability of the MNE group. The qualified profits are 30% of a sum which is calculated by applying the local revenue to the global profitability of the MNE group.

The taxing right is given to the jurisdiction from where the payment has been made. There could be an overlap with other articles, for example, business profits, royalties or fees for technical services. This is taken care of with the Commentary clearly specifying which one will prevail in case of an overlap.

There may be questions on why the solution is confined to automated digital services. The reason is simple: though there is ring-fencing, it focuses on one major segment which was of concern to the world.

In conclusion, there is no suggestion to tax digital businesses which is a matter of domestic law exclusively. Article 12B will come into play for a country which has chosen to tax digital businesses as is normally the case. Second, there is no interlinking with other issues. Third, the solution takes a traditional approach which is in a decentralized manner. This is a very important point because Article 12B is similar to article 5 read jointly with article 7 to which countries are used to, especially the developing countries.

Implementation concerns on how to insert article 12B in the treaties

This can be done through an instrument like the Multilateral Instrument (MLI). Countries can sign it and then the proposed article can get inserted in all their bilateral tax treaties without the need for individual renegotiation of each treaty.

An incentive for the adoption of 12B by countries could be the possible end to unilateral measures, equalization levies and Digital Service Taxes. One of the reasons why there is so much of concern regarding these is because they are circumventing the tax treaties and for them the tax credit is not available. However if article 12B is inserted in the treaties, these taxes are slightly remodeled and they are made covered taxes under the bilateral tax treaty which has this article then this automatically will take care of the unilateral measures.

Pooja Rangaprasad, Director of Policy and Advocacy, Society for International Development, spoke about the importance of transparency and institutional legitimacy in rulemaking and norm-setting and how these can lead to the creation of rules which are in the interests of a wide set of participants and not just a select few. When it comes to the question of rule-making, she emphasised that "Pillar 2 takes away the attention from Pillar 1 which is about allocating taxing rights". According to her, the rules must be taken up in the United Nations, because it has wide country membership, which gives it a level playing field setting the base for them to be discussed in a more transparent manner. She concluded by saying that it is not enough for countries to engage with these issues as a standalone, but rather to deal with them politically as a whole to have a broader understanding of what is at stake.

Fernando Rosales, Coordinator of the Sustainable Development and Climate Change Programme of the South Centre, made three closing remarks:

(1) Processes at the OECD are usually dominated by developed countries. Developing countries should fight for their interests so as not to perpetuate the status quo that relegate developing countries’ interests in the international tax framework.

(2) Developing countries should not lose the economic and political side of this whole process. This topic is not only a technical issue. Developing countries should include in its analysis the political and economic perspectives to have a broader and more comprehensive understanding of what is at stake.

(3) The OECD solutions are not the only ones. Developing countries should not dilute their ambition in reforming the tax system. There are other avenues in terms of international tax developments such as the work conducted by the UN Tax Committee which has a specific mandate to work for the interest of developing countries. Ultimately, countries can and should resort to their domestic laws to build their own tax systems according to their own realities and needs.

Authors: Aaditri Solankii ([email protected]) is an intern with the South Centre Tax Initiative, part of the Sustainable Development and Climate Change Programme (SDCC) of the South Centre. Khalid Phul is a Tax Associate at EY RDS (Mauritius).

[1] The event details can be found on https://taxinitiative.southcentre.int/event/build-your-house-on-your-own-pillars-key-issues-for-developing-countries-at-the-oecd-inclusive-framework-negotiations-on-the-taxation-of-the-digital-economy/.

[2] The presentation can be accessed on https://www.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Presentation-by-Carlos-PROTTO-SC-Webinar-on-Taxation-of-the-Digitalised-Economy.pdf.

[3] Gross domestic product might be used as a demarcating factor.

[4] See https://taxjustice.net/2021/04/15/the-metr-a-minimum-effective-tax-rate-for-multinationals/.

[5] The presentation can be accessed on https://taxinitiative.southcentre.int/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/South-Centre-Event-on-UN-approach-15th-JUne-2021-Rajat-Bansal.pdf.

[6] See https://www.un.org/development/desa/financing/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.financing/files/2020-06/CICTM%2020th_CRP.25%20_%20Digitalized%20Economy.pdf.