Shutterstock.com

This is the second in a series of blogs about internet access in Indonesia.

A well-functioning digital economy requires widespread access to high-quality internet. Although internet use in Indonesia has nearly quadrupled over the last decade, every second Indonesian adult remains unconnected.

In addition, almost all internet users Indonesia connect through mobile devices. Although mobile broadband (3G, but now increasingly 4G/LTE) is the most widely used internet service in Indonesia, it is not on par with fixed broadband with respect to capacity, quality of service, high bandwidth performance, and cost-efficiency. Distance learning efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic recently highlighted the limitations of mobile internet as millions of students and teachers across Indonesia found their mobile data plans inadequate and prohibitively costly for high bandwidth applications.

Such limited access to high-quality internet prevents the population from unlocking its productive capabilities to fully reap the benefits of a digital economy and points to two key challenges: how to make fixed broadband internet access universal and increase internet quality.

Increased optical fiber network coverage is a necessary but insufficient solution to meeting the key challenges. While investment by private service providers, along with government projects such as Palapa Ring[1] have steadily increased connectivity and service availability across Indonesian districts, internet subscriptions have not increased in parallel. Only 26 percent of homes with access to a fixed broadband provider subscribe to this service.

The low subscription rates are attributable to a large extent to cost and quality concerns. While Indonesian mobile broadband data packages are relatively affordable compared to similar packages offered by Indonesia’s regional peers, fixed broadband packages are not. In the 2019 ITU rankings on fixed line subscription fees, Indonesia ranked 131st in affordability out of the 200 countries and territories observed, confirming that Indonesia is one of the most expensive markets for fixed broadband. Almost half of Indonesia households -- 44 percent -- cite high costs as the main reason they do not subscribe for fixed broadband services.

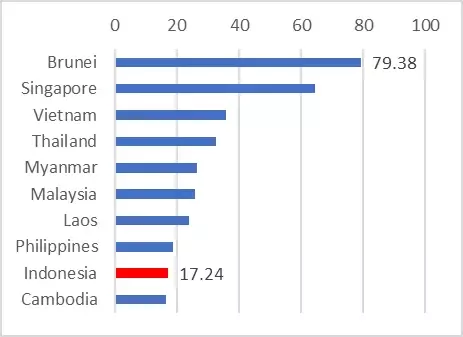

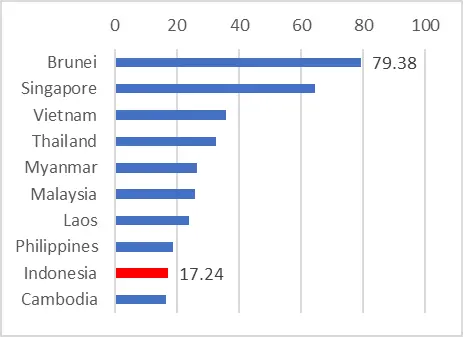

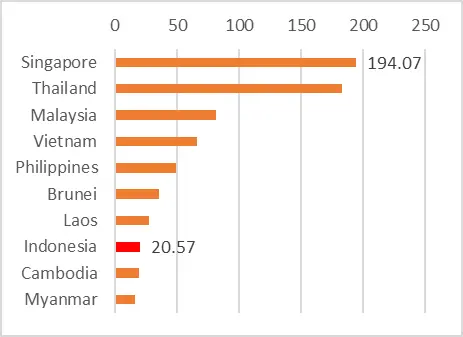

On top of expensive fees, the quality of internet service in Indonesia is among the lowest compared to its ASEAN neighbors. Indonesia records the second slowest mobile broadband (17.24 Mbps) download speed—only narrowly surpassing Cambodia, at 16.4 Mbps—and the third slowest fixed broadband speed in ASEAN, after Cambodia and Myanmar.

Mobile and fixed broadband throughput (Mbps)

Source: Ookla Speedtest, February 2022.

Note: Mobile broadband speeds in the left panel and fixed broadband speeds in the right panel.

Why is internet in Indonesia relatively expensive and slow?

Two main factors contributing to the high price and low quality of Indonesia’s internet connectivity. While infrastructure sharing is a common practice among mobile networks, it is not prevalent in the fixed internet broadband market. Between 70 percent and 80 percent of the costs for fixed broadband are typically attributable to passive infrastructure such as ducts, poles, right-of-ways, and civil works. Sharing costs among providers would bring benefits, lower outlays for acquisition, leasing, and maintenance.

Secondly, the restrictive licensing scheme makes service providers bid for service-specific licenses instead of providing a single uniform license for all services. This reduces competitiveness in the broadband market by limiting market entry, which leads to higher prices for consumers for lower quality service, inhibiting broadband internet adoption.

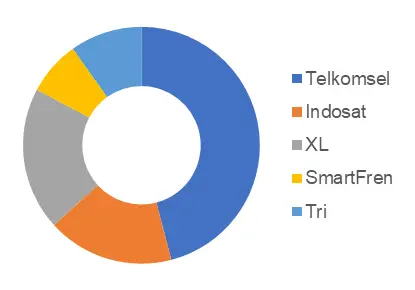

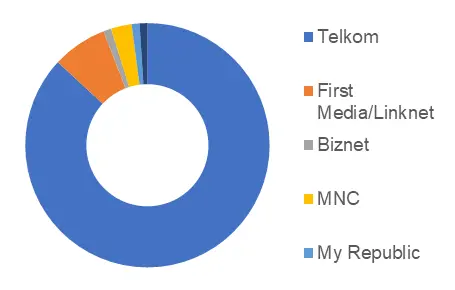

While the mobile broadband space is competitive, the fixed broadband market is more concentrated, with Telkom dominating the market share

(Subscription shares of various providers)

Source: Subscription data, various sources. Estimates for subscription number are extracted from each respective company’s 2018 Q3 investor memo.

Note: Mobile broadband subscription share in the left panel and fixed broadband subscription share in the right panel by providers

To address these regulatory bottlenecks, Indonesia could consider two policy measures as suggested in the World Bank’s Beyond Unicorn report. First, the government could act to encourage active and passive infrastructure sharing. Recently enacted rules are a good start demonstrating government efforts to boost passive infrastructure sharing. Follow-up enforcement will be important. In addition, the regulation of passive infrastructure sharing and rapid and effective dispute resolution should be the responsibility of a single entity. Finally, public-private partnerships could be leveraged to accelerate investments in connectivity. For example, internet service providers could cooperate with public service providers to use already available public telecommunication poles and underground lines for fiber optic deployment.

Second, Indonesia should strengthen competition along the broadband value chain by simplifying the licensing process to encourage entry of new participants and development of more advanced products. Consumers should also be given the possibility to switch between service providers by enabling transferability of telephone numbers across providers.

Do you have any views on how to improve Indonesia’s internet access and quality? Please share in the comments box below.

This blog post is part of a series of blogs discussing the digital divide in the context of broadband internet access, mobile internet access, digital economy and digital governance, relying on results of the Beyond Unicorn report.

[1] The Palapa Ring project, a private-public partnership (PPP) led by the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (Kominfo) and implemented during 2015–19, has succeeded in extending the domestic backbone to the entire country. The original Palapa Ring project was divided into a commercially feasible part and a commercially non-feasible part. The commercially feasible part (457 districts/cities) was undertaken by the private sector and included the routes from Lombok to Kupang, SMPCS (Sulawesi-Maluku-Papua-Cable-System) up to Jayapura and Merauke, and several smaller cable projects. The commercially non-feasible part of Palapa Ring (57 districts) was financed through the Universal Service Obligation (USO) Fund (financed by a levy on the net revenues of the telcos) and was also deployed in 2015–19.