Arne Hoel/World Bank

The COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionally affected poor urban communities and laid bare pre-existing inequalities – including a digital and social divide that has been further exacerbated by the pandemic. As per our recent study, only one of every 26 jobs can be done from home in low-income countries, and across the globe. Young, poorly educated workers and those on temporary contracts are least likely to be able to work from home and more vulnerable to the labor market shocks from COVID-19. How can this digital divide be closed? The experience of a small team from the World Bank shows that efforts to collect data can offer opportunities to expand digital literacy in local communities.

In 2020, the World Bank team partnered with Slum Dwellers International (SDI) and Cities Alliance to collect geospatial data for the most vulnerable informal settlements (including access to basic services) in eight cities to improve and validate the COVID-19 contagion risk hotspot mapping. But what started as a data-gathering exercise became a larger pilot going beyond its original scope and leading to varied direct and indirect positive outcomes.

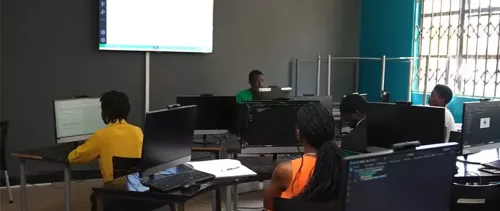

One such outcome was enhanced digital skills of local SDI affiliates -- support non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and urban poor federations - in five countries. The World Bank formed a small team of geospatial data experts and trainers to design and deliver these trainings, and, along with the broader SDI team, created an interactive seven-week virtual-training program. SDI country-based teams include mappers and urban planners with varying levels of geospatial skills (basic to semi-advanced). Therefore, we co-designed the content with SDI based on the existing skillsets of trainees and with their specific needs in mind.

The content of these trainings ranged from open data tools and mapping to remote sensing data tools, advanced geo-spatial data analytics, and data visualization tools. The team of trainers designed three modules, each six to seven hours and sub-divided into technical, demo, and practice sessions. We recorded and shared all trainings with trainees, and every week, we provided materials to practice tools offline. This interactive model allowed for a deeper level of understanding and better application of tools while making the transition from theory to actual implementation on-ground easier.

These capacity-building trainings came in handy for the local teams during field data collection and focus group discussions. For example, the Open Data Kit (ODK) and Kobo toolbox was used to collect data more efficiently and accurately during the pandemic. Similarly, satellite imagery allowed teams to digitize, validate, and edit some of the data points while they could not travel to informal settlements due to lockdown and other mobility restrictions. Advanced QGIS tools helped in analyzing the data. By estimating the number of people using a public facility and network analysis to the proximity of these facilities. Lastly, story maps and other interactive visualization tools were helpful in SDI’s advocacy work.

The additional chain of people trained by the original cohort of trainees represented the positive spill-over effect. Each country team conducted a series of trainings for additional team members, traveling the field for data collection. For example, the SDI Kenya team of five trained 150+ mappers/volunteers/local community members within the course of a few weeks.

Focus group discussions highlighted a strong demand amongst local communities (especially youth) for digital skills trainings, as it can potentially improve their employability prospects. As quoted by a Freetown resident during discussions, “we need more of these vocational training for our youth, as most of them are unemployed which leads them to steal and gamble for money.”

To conclude, community-led data collection can provide an entry point to engage with the community and deliver skills training, starting with geospatial skills to broader digital and vocational skills. This can have several collateral benefits for local communities in post-pandemic cities, from disaggregated data collected and owned by communities for evidence-based planning to improved skills for changing the job market, community empowerment, and opportunities to partner with cities in decision-making. The World Bank and SDI are jointly exploring avenues to scale up these trainings to a broader network of local mappers, volunteers, and community members in more cities.

SDI network brings together over a million informal settlement dwellers in over 30 countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, who work together through federations and support NGOs to collect city-wide data and information on informal settlements, and in this process, they train youth, volunteers, and slum residents on a recurrent basis and advocate for their rights.

The World Bank team included Swati Sachdeva (Urban Specialist); Nagaraja Rao Harshadeep (Lead Environmental Specialist and Global lead for disruptive technology), Yves Barthelemy (Senior Geospatial consultant), Nuala Margaret Cowan (Senior Geospatial consultant), Hrishikesh Prakash Patel (Geospatial consultant) and Isabel Maria Ramos Tellez (Geospatial Consultant).