Over the past decade, the African Centers of Excellence (ACE) have trained thousands of students in key fields such as health, agriculture, digital technology, energy, and the environment. But behind the numbers lies a powerful ambition: to equip Africa’s youth with the skills to meet the continent’s challenges, and to build sustainable bridges between universities, businesses, and public services.

BRIDGING TALENT

From Brain Drain to Brain Retained

The sun is already beating down on the paved walkways of Gaston Berger University in Saint-Louis. The first lectures have just ended. Within minutes, the quiet paths fill with chattering students, headphones on or books in hand.

“Here in Senegal, only 2% of students who start primary school make it to university. So, you can imagine how determined they are,” says Maïssa Mbaye with a smile.

Tall, lean, and with the air of an eternal student, the professor makes his way to the digital science research lab where he teaches at the master’s, PhD, and postdoc levels. He waves to a colleague and quickly answers a student’s question without breaking stride.

Many of us have encountered a teacher who quietly changed the course of our lives. Maïssa Mbaye met three.

“Three high school teachers completely changed everything for me through their kindness, their enthusiasm, and their high standards,” he says.

Raised by his grandparents, he earned a science baccalaureate, followed by a master’s degree from Gaston Berger University. A research grant took him to France.

A brilliant career abroad was within reach. But Maïssa chose to return.

“I received a lot here at Gaston Berger. I wanted to give back.”

His lab hums with energy. It’s a focused, collaborative hive where ideas circulate freely. From nanotechnology to artificial intelligence, from software development to agricultural drones, each project shares a common goal of fostering research that serves development.

One team has worked on early diabetes detection. Another developed drone-based imaging tools to help small-scale farmers monitor their crops and prevent soil degradation. The focus here is on modernizing public services, digitizing hospitals, and making innovation accessible to artisans, farmers, shopkeepers, and mechanics alike.

“We also support small and medium businesses and informal sector vendors, who represent 90% of Senegal’s economic activity,” explains Maïssa Mbaye. “We even created a special certificate program for those who don’t have a high school diploma.” The goal is to include, not exclude. To make digital technology a gateway, not another barrier.

“And we collaborate with the public sector, PhD student Al-Hassim Diallo, for instance, designed a digital medical record system for Saint-Louis Regional Hospital. Now, patient information is centralized, accessible remotely, and traceable.”

This has resulted in faster care, fewer errors, and more lives saved.

“We also support small and medium businesses and informal sector vendors, who represent 90% of Senegal’s economic activity. We even created a special certificate program for those who don’t have a high school diploma.”

Maïssa Mbaye, Director of the African Center of Excellence in Mathematics, Computer Science, and ICT (MITIC), Saint-Louis, Senegal, from 2020 to 2024

Saving lives is also Abdoul Aziz Diouf’s mission, and to do that, healthcare must be decentralized. Women living far from Dakar deserve the same quality of care as those in the capital.

This is why the professor of medicine and gynecology has left the quiet campus of Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar for the day. He’s traveling to Fatick, three hours away, to supervise a student from the university’s endoscopy diploma program as she performs her first solo procedure.

In a country where 41% of healthcare infrastructure is concentrated in Dakar—which makes up only 0.3 % of the territory—providing care in Fatick is almost an act of defiance. In rural areas, there is one hospital for every 500,000 people and one health center for every 150,000. Across Africa, the disparity is even starker: 83 % of rural residents lack access to essential healthcare, compared to 22% in urban areas.

It’s noon. Outside the hospital, the dry heat of Fatick weighs on the town. Husbands and grandmothers wait patiently under the arched entry or the shade of acacia trees—some for their wives, others for their daughters. Inside, it's just as quiet. In the operating room, clad in blue scrubs, Mame Faye guides the endoscopic tool with precision. Behind her, Professor Diouf speaks softly, offering guidance. Every movement counts.

Just five years ago, Senegal had no training program in endoscopy at all. “My greatest pride is seeing my students perform procedures on their own, without mistakes,” Diouf says. “That’s the strength of this program: it’s based on practical skills, not just theory.” Now, in parts of Senegal once considered unreachable, students are learning to perform surgeries locally. “Years ago, the idea of having a gynecologist 700 kilometers from Dakar seemed impossible,” he adds.

Through this program and others, faculty members train doctors, midwives, and health technicians. “Most are Senegalese, but some come from across the continent—Cameroon, Madagascar, even Tunisia,” Diouf notes, proud of the program’s diversity. All of them travel regularly beyond big cities to meet patients where they are, rather than asking them to travel for care.

In Méouane, in the Thiès region, for instance, women and children wait calmly under a tent in the village square. Despite the searing heat—more than 109 degrees Fahrenheit in the shade—the atmosphere remains orderly. A medical bus pulls in. It’s one of the mobile clinics developed by teams at Cheikh Anta Diop University. On board are two young interns, along with a state-of-the-art mobile care unit with two consultation rooms—one for gynecological care, one for pediatrics. The equipment enables ultrasounds, diagnostics, and deliveries in safe conditions. Between the exam rooms, a small pharmacy allows patients to leave with prescribed medication in hand. This kind of service is vital in a context where health outcomes remain fragile. Despite a 58% drop between 1990 and 2017, Africa still has the highest child mortality rate in the world. In 2021, the continent accounted for over half of the 4.9 million global deaths of children under five.

In the pediatric consultation room, Abdourahim Ben Cheikh examines a five-year-old girl. She’s showing signs of vision loss, likely caused by a vitamin A deficiency—a leading cause of childhood blindness in developing countries when not caught early.

A fourth-year pediatric intern, Abdourahim is now used to the pace of mobile clinics. Nothing like the intensity of Touba during the 2022 Grand Magal, when 14 interns in pediatrics and gynecology treated 600 patients in one day, from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m.

Originally from the Comoros, Abdourahim completed his general medical studies there before coming to Senegal to specialize. “In two months, I’ll be a pediatrician. I’d like to pursue a specialization in pediatric cardiology and work outside Dakar, where the need is greater.” Like him, many are choosing this path. At each stop, the mobile clinic does more than provide specialized care. It collects key data to inform research and shape practical, data-driven health solutions.

“My greatest satisfaction is that we managed to create a skills-based degree—not just a theoretical one. And the results speak for themselves. A few years ago, the idea of having a gynecologist 700 kilometers from Dakar, equipped to perform endoscopies, seemed unthinkable.”

Professeur Abdul Aziz Diouf-Professor of Medicine and Gynecology, Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar, Senegal

Hadiza Galadanci is also searching for answers—not abstract or theoretical ones, but tangible solutions capable of shaping public policy. A professor of obstetrics and gynecology and research director at Bayero University in Kano, northern Nigeria, she splits her time between lecture halls, delivery rooms, and policy meetings.

“I was lucky to have a father who was a university professor and insisted we receive a solid education,” she says. Her father's support and high expectations carried her further than she could have imagined.

Now, the first woman gynecologist in her state, she has since trained many others who are also passing on their knowledge.

“I tell young girls again and again: if you get a good education, nothing will stop you. There’ll be no ceiling above your heads.”

Her other mission is to help Africa shed its grim distinction as the continent with the highest rate of postpartum hemorrhage in the world. “Every two minutes, a woman dies giving birth somewhere in the world. A quarter of those deaths are due to postpartum hemorrhage. And 65% of them happen in sub-Saharan Africa.”

Hadiza refuses to accept this reality. Her hope is that rigorous, field-based research can help influence political decision-making. “What we teach our students isn’t just how to conduct research—it’s how to translate that research into real, applicable policy recommendations,” she explains.

For her, two levers are key: building strong skills and forging solid partnerships.

“Our center has already trained thousands of health workers in the prevention and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. We also work hand in hand with partners like the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.”

“I tell young girls again and again: if you get a good education, nothing will stop you. There’ll be no ceiling above your heads.”

Hadiza Galadanci, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Founding Director of African Centre of Excellence in Population Health and Policy, Bayero University, Nigeria

In the east of the continent, George Owuor is also working to open the doors of higher education to young women. At Egerton University in Kenya, he decided to change things—steadily, but surely—so that student mothers could continue their studies.

This specialist in sustainable agriculture established support measures on campus, such as access to adapted housing and on-site childcare.

Today, more women are entering the university’s agriculture labs. Four out of every ten students are women. It's a quiet but essential victory in the agricultural sector that, on its own, supports nearly two-thirds of the working population in low-income countries. “Every female graduate is a step forward in reducing inequality—and a step closer to a more inclusive future.”

Trained in Kenya and Germany, George bridges academic research with hands-on projects, working closely with rural communities. He advocates for an inclusive vision of agriculture—one that directly responds to the needs of farmers, creates jobs, and improves nutrition. As food insecurity worsens, affecting more than 60 million people in East Africa and nearly 50 million in West and Central Africa, every innovation matters.

For George, agriculture is more than just an economic driver, it is a vital force. “To nourish is to heal.”, he likes to say.

A more sustainable future is also what others, like Denis Worlanyo Aheto in Ghana, are working to build by focusing on environmental protection. In the coastal city of Cape Coast, nestled along the Atlantic, this professor of coastal ecology has stepped away from the university campus for a few hours. He’s headed to a nearby fishing village, where one of his master’s students is carrying out a field project to combat plastic pollution.

“I initially studied marine biology, but quickly realized I was more passionate about natural resource management and coastal protection,” he says. This is no small issue—West Africa loses nearly two meters of coastline to the ocean each year. Aheto’s academic path took him from Ghana to Sweden and Germany on scholarship

Today, he ensures that his students’ work has real-world impact.

“I want research to make a tangible difference in people’s lives.”Denis Worlanyo Aheto , Director for Centre for Coastal Management and the Africa Centre of Excellence in Coastal Resilience, Cape-Coast University, Ghana

His teams have mapped plastic pollution hotspots along the coast, and this meticulous work now informs local waste management policies. Other initiatives focus on schools, teaching children from a young age how to protect the ocean. Once again, science steps out of the lab and into everyday life.

A little further east, across the border in Togo, Jacob Kokou Tona shares the same conviction. At the University of Lomé, the poultry science professor guides his students with one clear objective: strengthening ties between academic research and the private sector to create jobs.

“We have partnerships with Hendrix Genetics—the world leader in animal breeding—and other agribusinesses in Africa and around the globe. These collaborations are essential to fund our research,” he explains. Professor Jacob Kokou Tona, Director, Regional Center of Excellence in Poultry Science, Lomé, Togo

For Tona, the solution lies in connecting science to farming. His path began with a master’s degree in agronomy in Togo, followed by a scholarship in Belgium, where he chose to specialize in animal science. Poultry farming, in particular, fascinated him since childhood.

He went on to complete a PhD and discovered the sector’s potential. “Poultry can create income and jobs, but above all, it’s a direct response to food insecurity in Africa.”

Tona firmly believes chicken and eggs are the foods of the future for a continent experiencing rapid population growth. Increased agricultural and livestock productivity is essential to prevent worsening food insecurity.

Poultry—one of the few species whose embryo develops outside the mother’s body—can be raised quickly and at scale. It’s affordable, nutritious, and free from food taboos and religious restrictions.

Their stories converge—Maïssa, Abdoul Aziz, Denis, Hadiza, George and Jacob. All followed the same trajectory: leaving to learn, and then returning to teach, build, and innovate for their continent’s needs.

Each of them turned down prestigious, often better-paying careers in Europe, Canada, the United States, or the private sector. They chose to come back to build research labs in their own countries. Labs that serve a purpose. Labs focused on Africa’s most pressing needs.

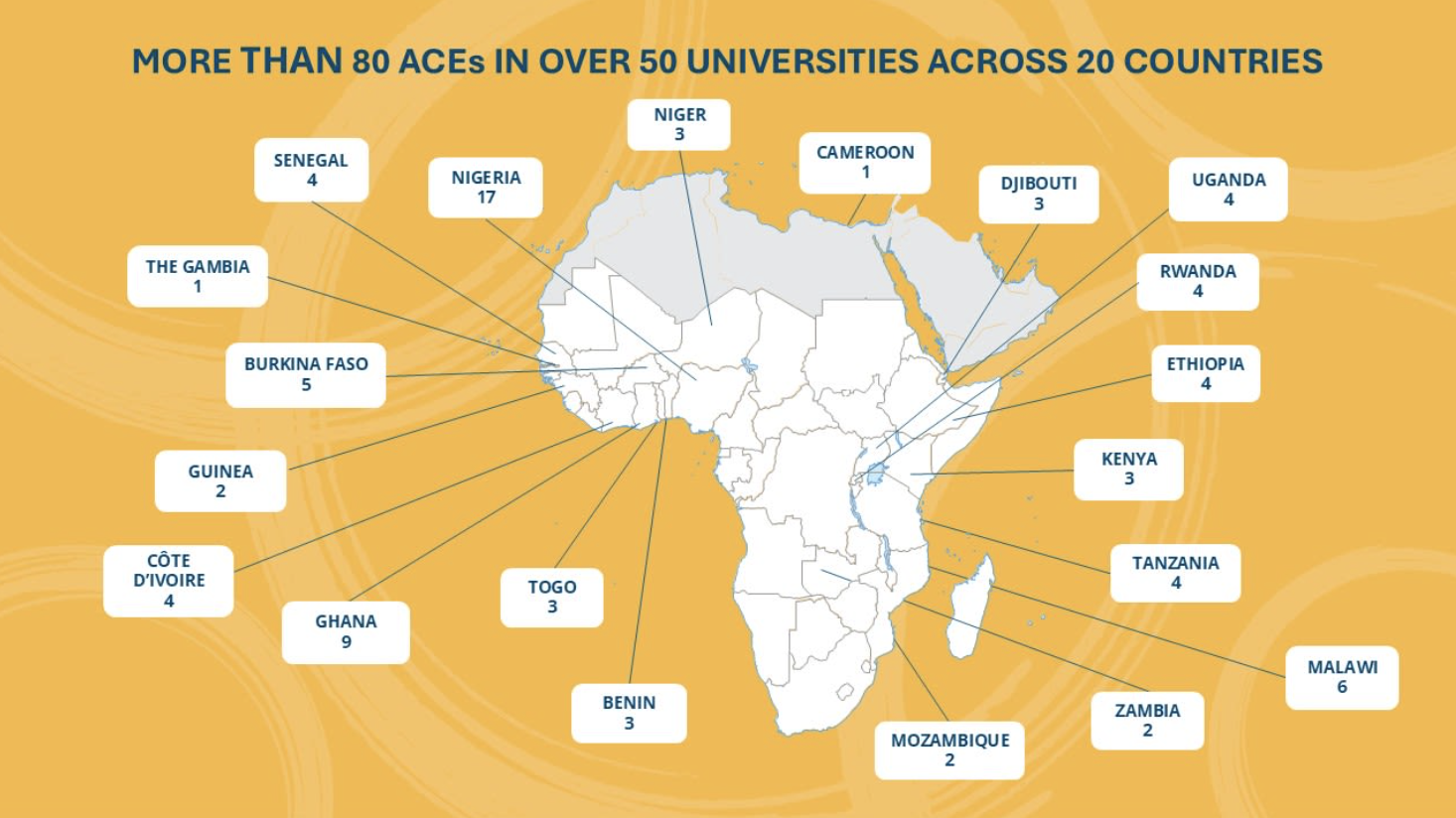

Today, they are the professors, directors, and thought leaders of one of 80 African Centers of Excellence hosted in 50 universities across 20 countries. Their mission is to train tomorrow’s talent by creating applied research programs that can offer practical solutions to local and regional challenges.

Health, agriculture, environment, education, energy, mining, transport and logistics, urban development, water, social sciences, and STEM—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. These are the pillars upon which they are building a forward-looking Africa.

The African Centers of Excellence (ACE) initiative was launched in 2014, born of a simple but urgent observation: each month, waves of new graduates enter the job market, only to find no formal employment opportunities. Urban populations are growing at an astonishing pace. By 2050, the continent’s urban population will have doubled, and an additional 700 million people will be of working age. One in three young people in the world will live in Africa.

Yet African universities are struggling to produce the skills local economies desperately need. In overcrowded lecture halls, more than half of students pursue degrees in law, business, or the social sciences. Fewer than 6% choose STEM fields—science, technology, engineering, and mathematics—and even fewer are women. If Africa is to diversify its economies, innovate locally, create sustainable jobs, and accelerate its transformation, it must rethink higher education.

The idea was bold: to create centers of excellence within existing universities—research hubs rooted locally, but aligned with international standards. Each center would be led by top African researchers, closely linked to national and regional priorities. Scientific results would not only be published but applied, commercialized, and shared, thus transforming research into economic and social progress.

But how can such centers be funded in universities that are often under-resourced? That’s where regional cooperation and support from the World Bank Group made the difference. By pooling resources across countries, governments created a coherent network attractive to students, researchers, and investors alike. The World Bank, through its International Development Association (IDA), provided funding and technical assistance, including a results-based disbursement mechanism: each time a milestone was reached—accreditation, publication, job placement—a portion of the financing was released.

The ACE program began with 22 centers in eight countries in Western and Central Africa: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, and Togo. Two years later, a second wave expanded the program to 45 centers in 18 countries, including in Eastern and Southern Africa. The program’s scope widened with additional themes, increased scholarships for women, new incubators, and entrepreneurship training integrated throughout the program courses.

Working in collaboration with the Association of African Universities (AAU) and the Inter-University Council for East Africa (IUCEA)—the regional implementing partners—and with $72 million in co-financing from the Agence française de développement (AFD), the ACE initiative became the World Bank’s largest regional higher education program in Africa, with over $657 million invested.

“When the World Bank Group is involved, other partners follow: foundations, philanthropic institutions, investors.”Eric Danquah, professor of plant genetics and director of the West Africa Center for Crop Improvement (WACCI) at the University of Ghana. Since its launch, WACCI has developed more than 80 resilient crop varieties, now cultivated by over a million farmers in ten African countries—boosting yields and stabilizing incomes

Ten years on, the mission of the ACEs remains unchanged: to pool resources, strengthen the quality of education and research, and build centers that reflect the continent’s development priorities. Today, these centers cover every major sector shaping Africa’s future.

But the ambition goes beyond academic disciplines. It’s about expanding horizons and building a new culture of collaboration. Student mobility is encouraged. Equipment is shared. Best practices are disseminated. Excellence becomes a collective endeavor—a living, growing network.

The African Centers of Excellence do not operate in isolation. They regularly convene ministries, researchers, professionals, businesses, and civil society at the same table to foster dialogue, share expertise, and ensure that research remains grounded in reality. These exchanges often spark unexpected collaborations—and sometimes lead to concrete innovations, such as new products, tools, and solutions ready to be applied in daily life.

In Kenya, for example, Moi University’s incubation center transforms waste into resources—from energy production to sustainable construction materials and circular economy solutions— as students learn to innovate in response to environmental challenges.

In Tanzania, Sokoine University developed Afyadata, an epidemiological surveillance app that allows health workers—and even citizens—to report outbreaks in real time.

In Nigeria, Senegal, and Rwanda, artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things are already part of university curricula, preparing the next generation of engineers and developers to tackle tomorrow’s digital challenges.

And in countries like Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda, progress in agricultural biotechnology has led to the creation of climate-resilient seeds—directly impacting food security.

Across the continent, the ambition is the same: to put science in the service of local, concrete, inclusive solutions.

And the numbers speak for themselves: Over 90,000 students have been trained, including more than 7,600 PhD candidates and 30,000 master’s graduates. More than 52,000 young people have received short-term professional training. The program has produced over 10,000 scientific publications, facilitated 18,000 internships or partnerships with businesses, and generated more than $184 million in external revenue—a sign of growing sustainability.

But beyond the numbers, the program’s quiet revolution can be seen in the personal journeys it has enabled. Behind every center and every lab are thousands of students reshaping their future, and that of their continent.

A Decade of Transformation: The ACE Journey at a Glance

2014 – THE STARTING POINT

The first 22 African Centers of Excellence (ACEs) open their doors in eight countries in West and Central Africa. The initiative is still relatively low-profile and experimental, but its ambition is clear: to train a new generation of African scientists locally, in high-quality academic environments.

2016 – SCALING UP

The program expands. It reaches East and Southern Africa. Twenty-three new centers are added, with a strong focus on women’s participation, entrepreneurship, and innovation hubs. Results begin to show. New specialized courses are launched—some for the first time in West Africa. Doctoral students from across the region enroll in large numbers.

2019 – IMPACT AT THE CORE

The program takes on a new identity: ACE Impact. Its priorities sharpen—university governance, sectoral alignment, measurable results. The goal is no longer just academic excellence but also economic, social, and industrial relevance. Training programs are aligned with labor market needs. Ties with the private sector strengthen. The model begins to inspire others.

2020 – A RAPID RESPONSE TO THE HEALTH CRISIS

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the ACEs proved their agility. The ACEGID center in Nigeria and WACCBIP in Ghana were among the first institutions in the region to sequence the SARS-CoV-2 genome, contributing to local understanding of the virus and supporting national response efforts.

2022 - AGRICULTURE TAKES THE LEAD

Feeding a fast-growing population requires immediate action. To tackle growing food insecurity on the continent, six centers dedicated to the agricultural sector are launched in Malawi and Mozambique. In these centers, 42% of students are women. Curricula focus on applied learning and value chain transformation. In Lomé, for instance, poultry science research has led to partnerships with major international firms.

2024 – TEN YEARS ON: A LASTING MOMENTUM

In just a decade, the ACEs have enabled dozens of African universities to acquire modern facilities and high-performing laboratories. The goal of training a new generation of researchers and engineers—locally and in good conditions—is taking shape. More and more students are choosing to stay on the continent. The challenge now: consolidate what has been achieved and expand its reach.

FROM LECTURE HALLS TO THE FRONTLINES

Meet the Next Generation of African Changemakers

“In five years, I see myself in a think tank, helping bridge research and public policy.”

Originally from Kenya, Rael Teresa Adhiambo pursued her PhD in oceanography at the African Center of Excellence in Coastal Resilience (ACECoR) in Ghana. Her research focused on the smallest links in the marine food chain—phytoplankton and zooplankton—and how climate change disrupts their development. These microscopic organisms are essential to the survival of marine species and to the food security of coastal communities. Her goal is to ensure her findings help shape science-based public policies in countries where fisheries play a vital role.

“Research is also a way to ensure better care for patients tomorrow.”

Originally from Malawi, Thomas S. Mughogho did his Master in Biomedical Sciences at the Wets African Genetic Medecine Center (WAGMC) where he studied the connection between diabetes and urinary tract infections—two major public health issues in sub-Saharan Africa. At WAGMC in Ghana, he explored how genetic factors influence patients’ susceptibility to infections, using genomic medicine to improve outcomes.

“What I loved most was the participatory fieldwork, meeting farmers and seeing how it reshapes your approach to science.”

As a child, Sandra Esi Adonkor, a Ghanaian researcher now holding a PhD in crop improvement from the West Africa Centre for Crop Improvement (WACCI), came across an unlikely newspaper story about a watermelon “filled with meat.” That curious article sparked a fascination with science. She went on to study agriculture at the University of Ghana, then specialized in plant breeding in the United States before returning to Accra for her doctorate. Her research focused on developing tomato varieties resistant to bacterial infections.

“What motivates me is seeing how a simple local solution can make a real difference in food security.”

A native of Togo and trained at CERSA, Mlaga Kodjo Nyatépé dedicated his doctoral research to a still underused but promising ingredient: maggot meal. Locally produced and richer in protein than soybean or fishmeal, it offers a sustainable alternative to these costly imported feeds. Alongside other students, he contributed to an applied research project at LoftyFarm, the largest fish farm in Togo, which had been severely affected by a 52% spike in soybean prices. Thanks to the experimental use of maggot meal developed with CERSA, tilapia production resumed. Mlaga hopes the center’s research can help shape future livestock policies across Africa.

“I wasn’t expecting it. My supervisor handed me the scalpel and said, ‘Go ahead, you can do this.’ It was my first C-section. I’ll never forget it.”

Selected by the Center of Excellence for Maternal & Child Health (SAMEF) to do a PhD after earning her medical degree, Élodie Kpekpede joined the highly selective specialist training in gynecology and obstetrics at Cheikh Anta Diop University. Now practicing, she is part of a new generation of women physicians—twice as many women as men are enrolled in the program. She plans to pursue a degree in public health next, to help shape preventive care policies.

“Machine learning can save harvests. Early disease detection gives farmers a real chance to feed their communities.”

Originally from Malawi, Chimango Nyasulu completed his PhD in computer science at the African Center of Excellence in Mathematics, Informatics, and ICT (CEAMITIC) in Senegal, where he focused on the invisible signs that precede rainfall, disrupt harvests, and shape the daily lives of farmers. He uses machine learning—a branch of artificial intelligence—to refine weather forecasting and detect crop diseases through image analysis with the aim of helping smallholder farmers better adapt, plan, and respond before it’s too late.

“By analyzing social media conversations, we can spot outbreaks earlier.”

Originally from Uganda, Harriet Cibitanga Missengisiguzi pursued a master’s in data science at the African Center of Excellence in Mathematics, Informatics, and ICT (CEAMITIC) in Senegal, where she explored an innovative approach: using artificial intelligence to analyze social media data and detect early warning signals—symptoms shared online or rumors of illness. Her goal: provide timely insights to public health actors before outbreaks spread. It’s a promising intersection of digital technology and epidemic surveillance, where online conversations can help trigger early responses on the ground.

“The innovations developed in high-income countries aren’t always transferable. Africa has its own realities—and its own needs.”

Now based in California, where he designs autonomous electronic systems, embedded systems engineer Abdourahmane Gaye has never lost touch with his native Senegal. In collaboration with the Center of Excellence for Maternal and Child Health (CEA SAMEF), he developed a solar-powered telemedicine case designed for rural areas. The device, easily transportable to local clinics, allows midwives to conduct medical imaging and connect with doctors in Dakar or abroad via a secure video platform to bring specialized care to remote communities, reduce travel time and costs, and train a new generation of technicians to maintain the technology.

In the next ten years, an additional 362 million young Africans will enter the labor market. Yet only 151 million jobs are expected to be created, leaving nearly a quarter of them unemployed. Today, Africa produces only a third of the jobs compared to regions with similar GDP per capita, meaning that economic growth is not translating into job creation. Faced with this massive challenge, Africa’s Centers of Excellence have proven over the past decade their ability to train highly skilled talent and to anchor innovation in local realities.

The impact of ACEs is tangible, measurable and visible. But their future is not yet guaranteed.

To sustain momentum, these centers must be equipped with the means to continue growing, innovating, building partnerships, and inspiring others. That requires clear and continued commitment from African governments, consistent funding, coherent public policies aligned with the centers’ goals, and support systems that match their potential.

The World Bank Group, for its part, remains convinced of their strategic value for Africa’s future—and will continue to support them with tailored tools and strong partnerships.

Because what is at stake is not only Africa’s future, but that of the world. By the end of the next decade, one in five people—and one third of all youth—will live in Africa. What happens here will shape the planet’s future.

And thanks to the universities and business partners of the African Centers of Excellence:

Photo and video credits: World Bank Group unless otherwise noted.