ⓒ SENUM

Whose language?

What is the language this website is written in? The letters that make up its source code? The very infrastructure of the Web itself? Is the language you write emails, essays and personal WhatsApp messages in the same as the language you grew up speaking or speak at home? Our daily lives are intertwined with the language that we use to interact, express ourselves, and create and consume information. With more than 5 billion people today being online or on digital platforms of some form, the language available and used online is important.

Despite there being over 7,000 spoken languages worldwide, Unicode – the standard for text and emoticons – only supports approximately 150. English content dominates over half of all written content online, despite only around 16% of the world’s population speaks this language. Only ten languages represent 82% of Internet content: English, Chinese, Spanish, Arabic, Portuguese, Japanese, Russian, German, French and Malaysian. Users are then expected to enter the online world using majority languages, which may vary greatly from Indigenous or non-majority languages commonly spoken in their given context. Users who speak languages with non-Latin scripts have an especially difficult time accessing content and sharing information in their mother tongue. This expanding digital divide is a result of uneven digital development and long lasting legacies of colonialism.

When languages are not digitally supported, users have less ability to take advantage of social media, e-commerce and other Internet platforms that are a part of global, daily life. An English-centric Internet reduces linguistic diversity and heightens the barriers for those who want to communicate in low-resourced or non-dominant languages in our digitized landscape.

Are we together?

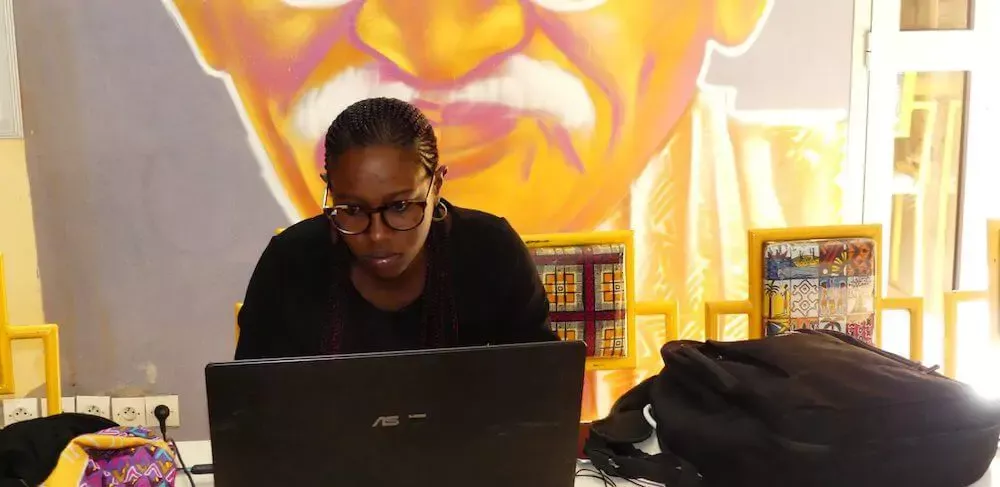

At Pollicy, we wanted to understand the use of Indigenous or non-majority language in the existing digital landscape. In partnership with the Digital Futures Lab, Design Beku, and generously supported by the Internet Society Foundation, we have completed a year-long project about the experiences and challenges that non-English speakers face online, focusing on issues of access, usability and safety. Through dozens of key expert interviews, over twenty focus group discussions, and fifteen ethnographic diaries, we aim to collate data and experiences of user groups and software developers to better inform stakeholders in the field on how to design, disseminate and implement applications and technology that better serve the majority of global populations: those who do not speak English as a first language.

Through data collected in Ethiopia, India, Tanzania and Uganda, we explore the user experience in East Africa and South Asia. Experiences range from: a non-dominant language as the national language (Tanzania), non-latin scripts dominate (Ethiopia), English still reigns as more useful and popular than local language (Uganda) and English is viewed as a lever to economic and social mobility (India). Users have to adapt due to both a lack of resources available in their known languages as well as the prevailing (primarily Western) norms that guide the structure of the Internet.

What now?

There are more questions than answers. Technology companies need to juxtapose profit with inclusion, content moderation with accessibility and recognize the diversity of their user base, particularly in the global South. We seek to amplify the need for non-majority languages to be resourced online, helping users enter digital spaces to maximize their benefits. The expansion of languages available online can empower and enrich user engagement, and should accurately reflect the average internet user.

More inclusive online spaces can simultaneously improve the access and use by non-English speakers and provide further avenues for endangered language preservation or revitalization (see examples of Hawaiian and Cherokee). Investment in non-English translation and content moderation tools may reduce the prevalence and influence of hate speech online (as seen in normal, English-focused content moderation). A focus on the languages outside of the Internet norm allows us to refocus on the “rest of world,” everyone outside of the West often left out of the conversation.

Read our white paper here, published in Amharic, Swahili and Luganda and English. Explore Pollicy’s full body of findings from this project on our microsite.