Banking kiosk in Borlai village, India. Photo © IFC

Digital infrastructure can significantly boost job creation, but it requires enabling policies and complementary investments in skills and physical infrastructure.

From mobile towers connecting remote villages to data centers powering digital economies, digital infrastructure is reshaping how firms, sectors, and countries operate. These investments are not just a symbol of modernization—they are catalysts for structural transformation and enable firms to create more jobs.

Digital infrastructure contributes to job creation directly, indirectly, and through induced effects. The sector directly employs workers, but its impact is amplified in indirect activities, such as Intelsat-Coca-Cola Wi-Fi kiosks in Africa, which empower local entrepreneurs, provide utility services, and foster self-employment. Likewise, app-based platforms lower barriers for small businesses and drive entry of new types of activities and jobs. The effects do not stop here. The induced effects of digital infrastructure on jobs emerge as digital technologies further penetrate sectors such as healthcare, education, and financial services. For example, technology-enabled training programs can scale firm upgrading and contribute to their ability to create jobs, as documented in a recent Emerging Market Insights note.

FIGURE 1

Labor market outcomes

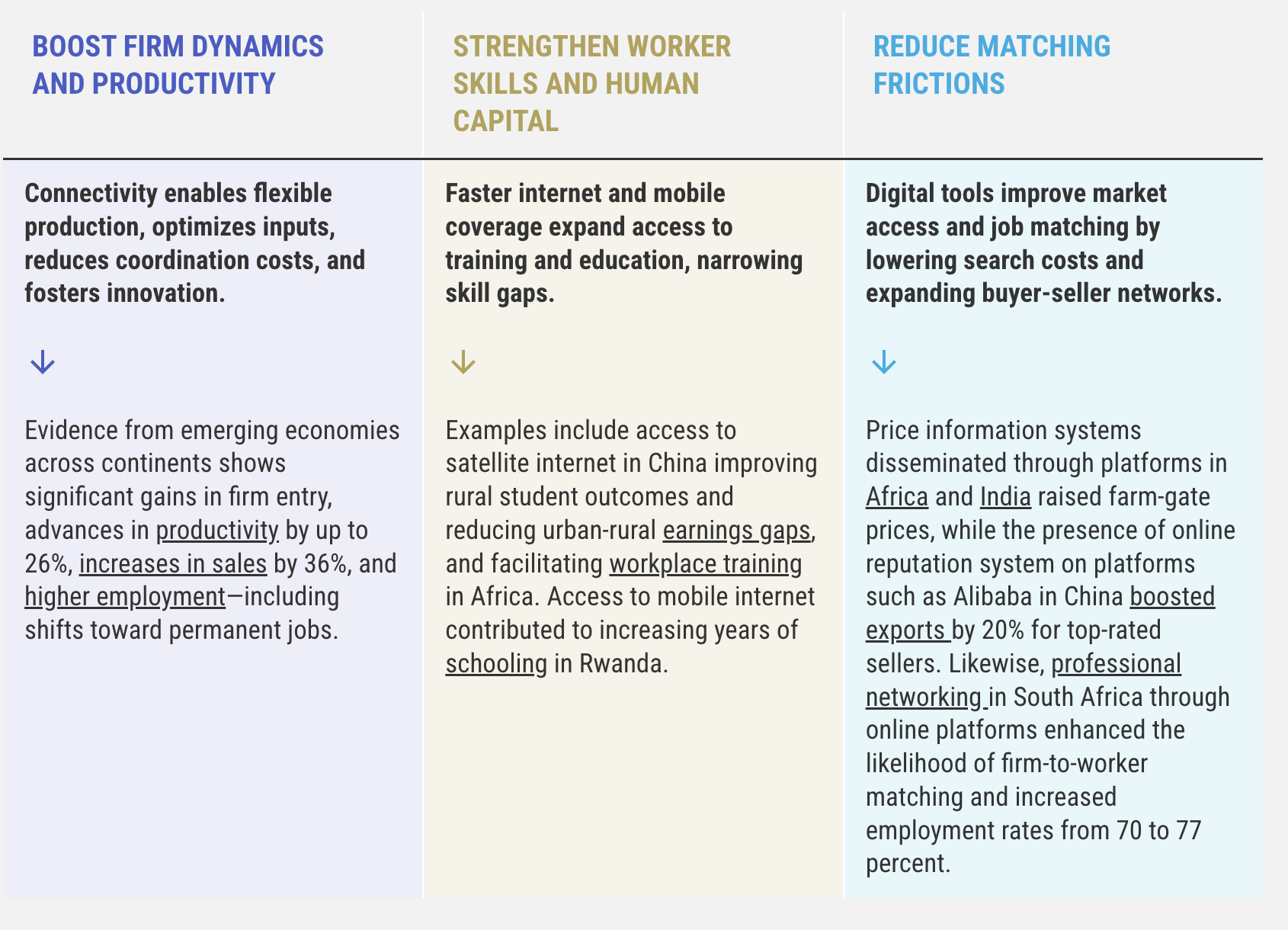

Digital technologies reshape labor markets through three broad mechanisms:

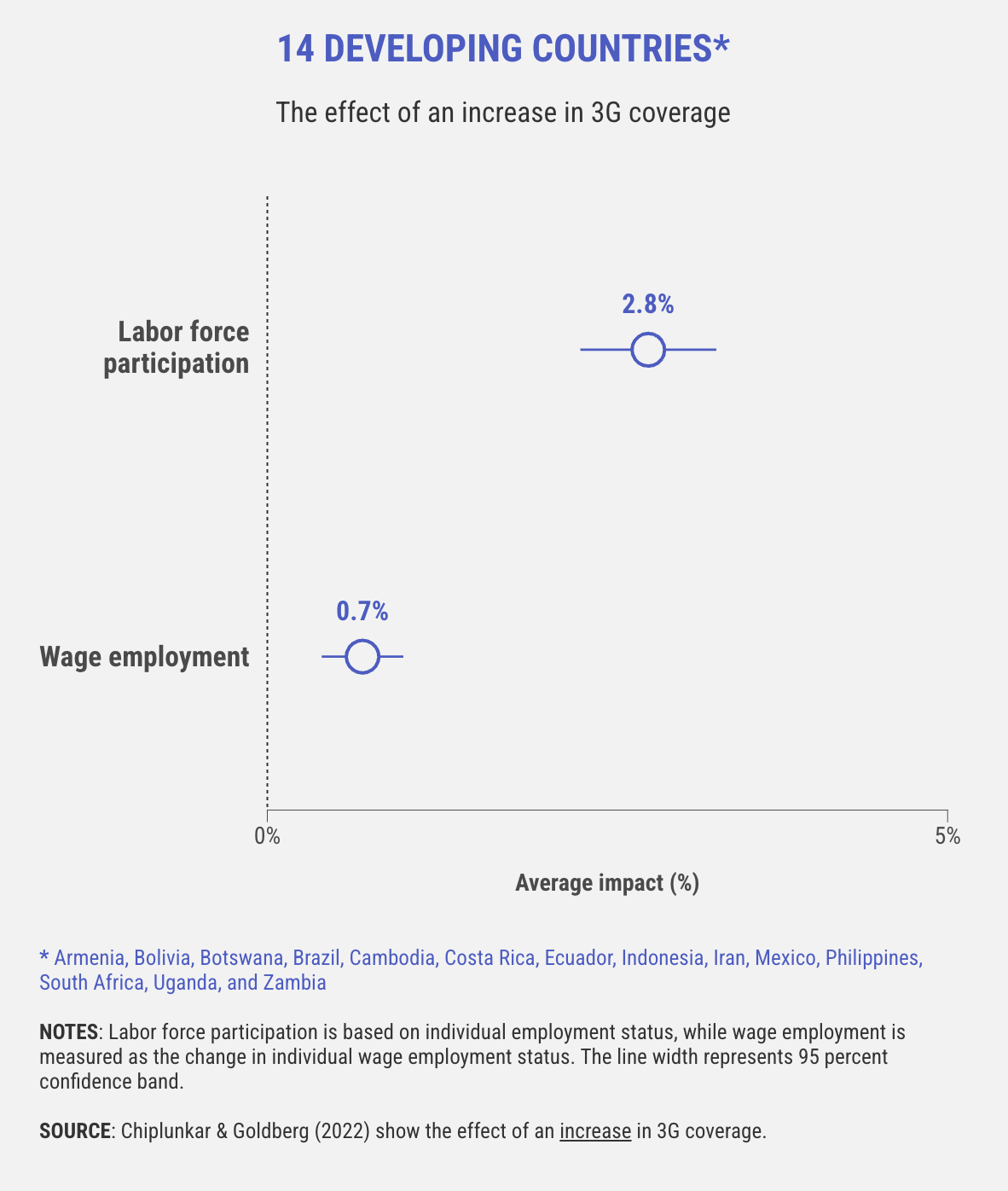

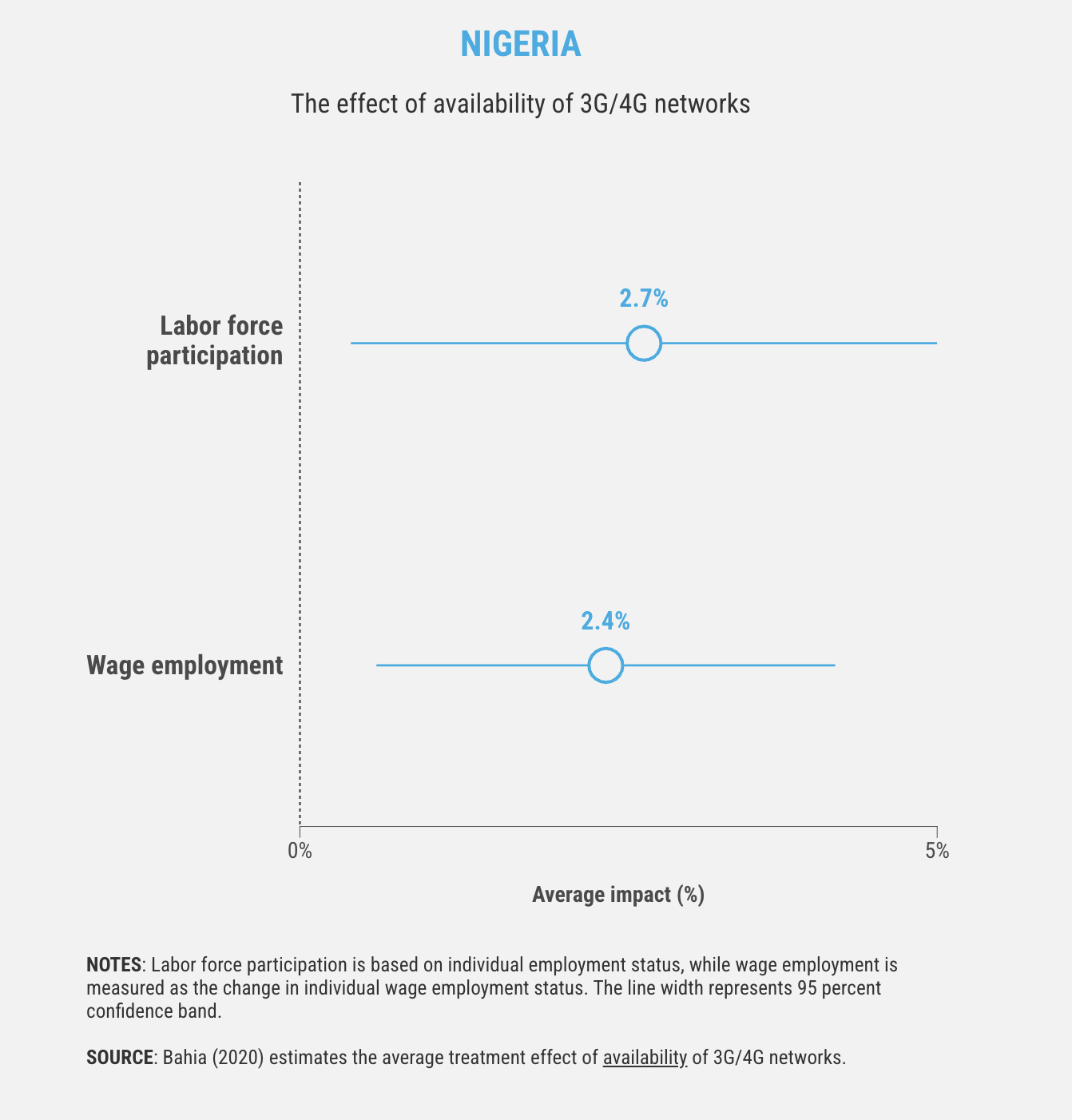

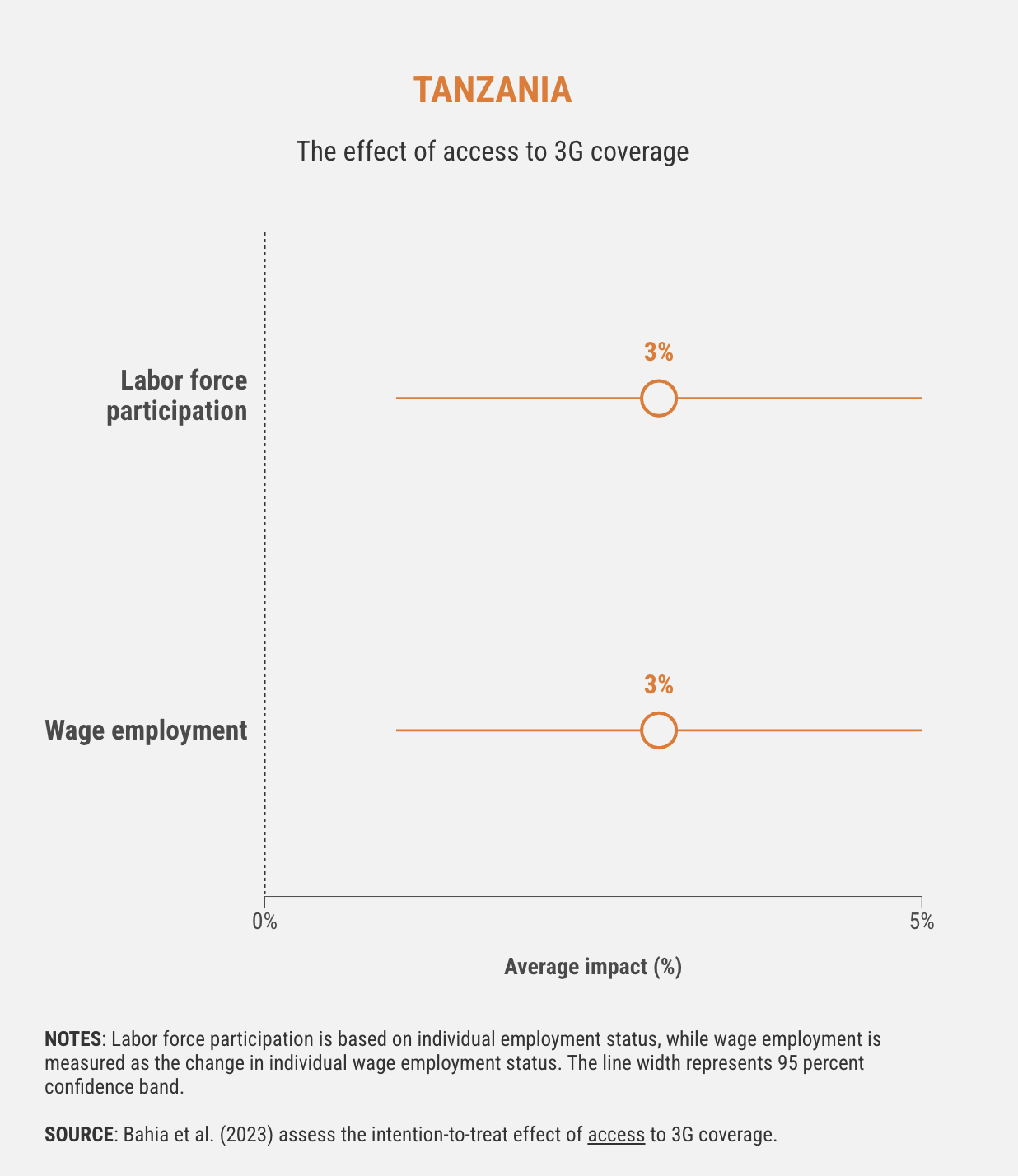

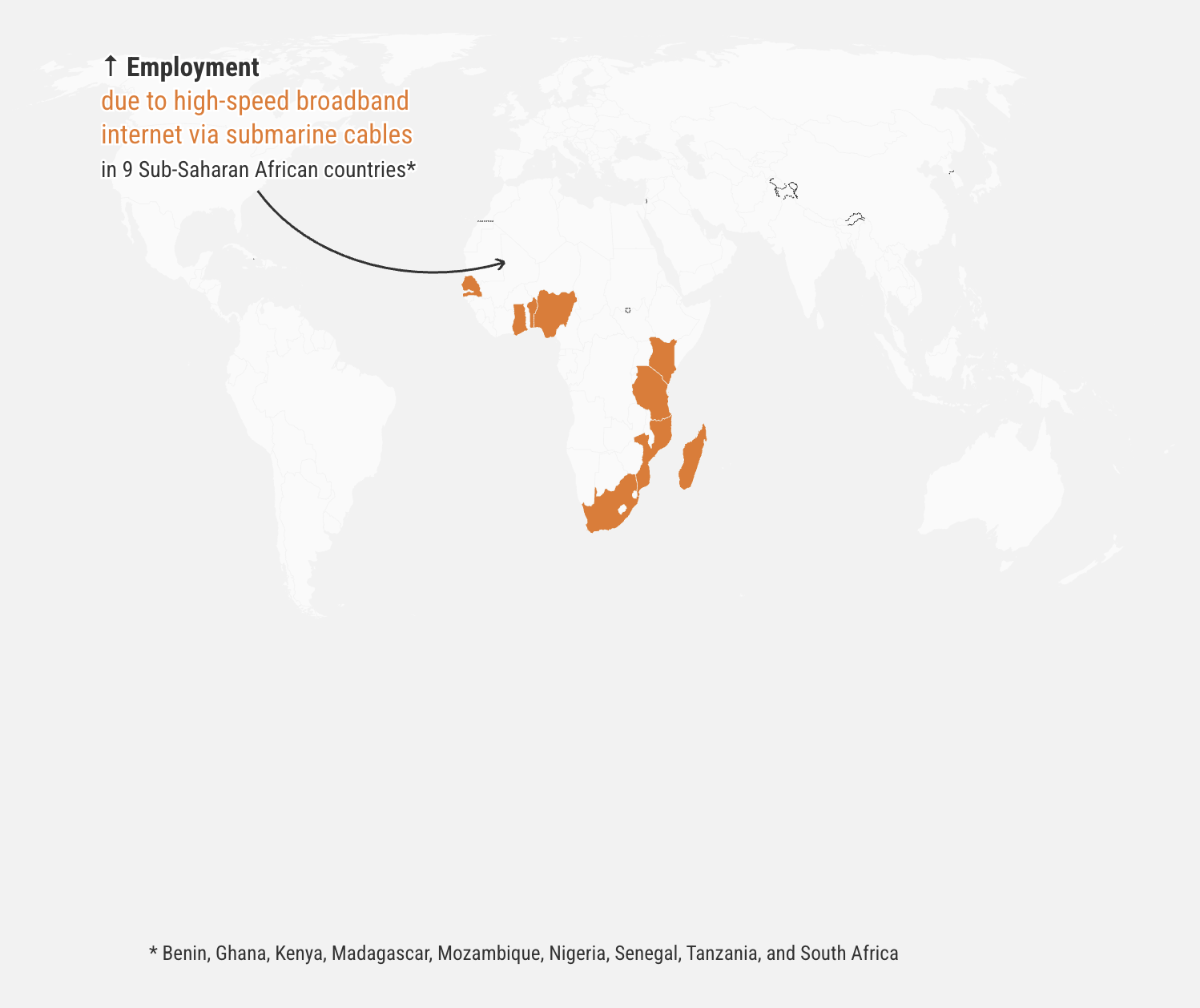

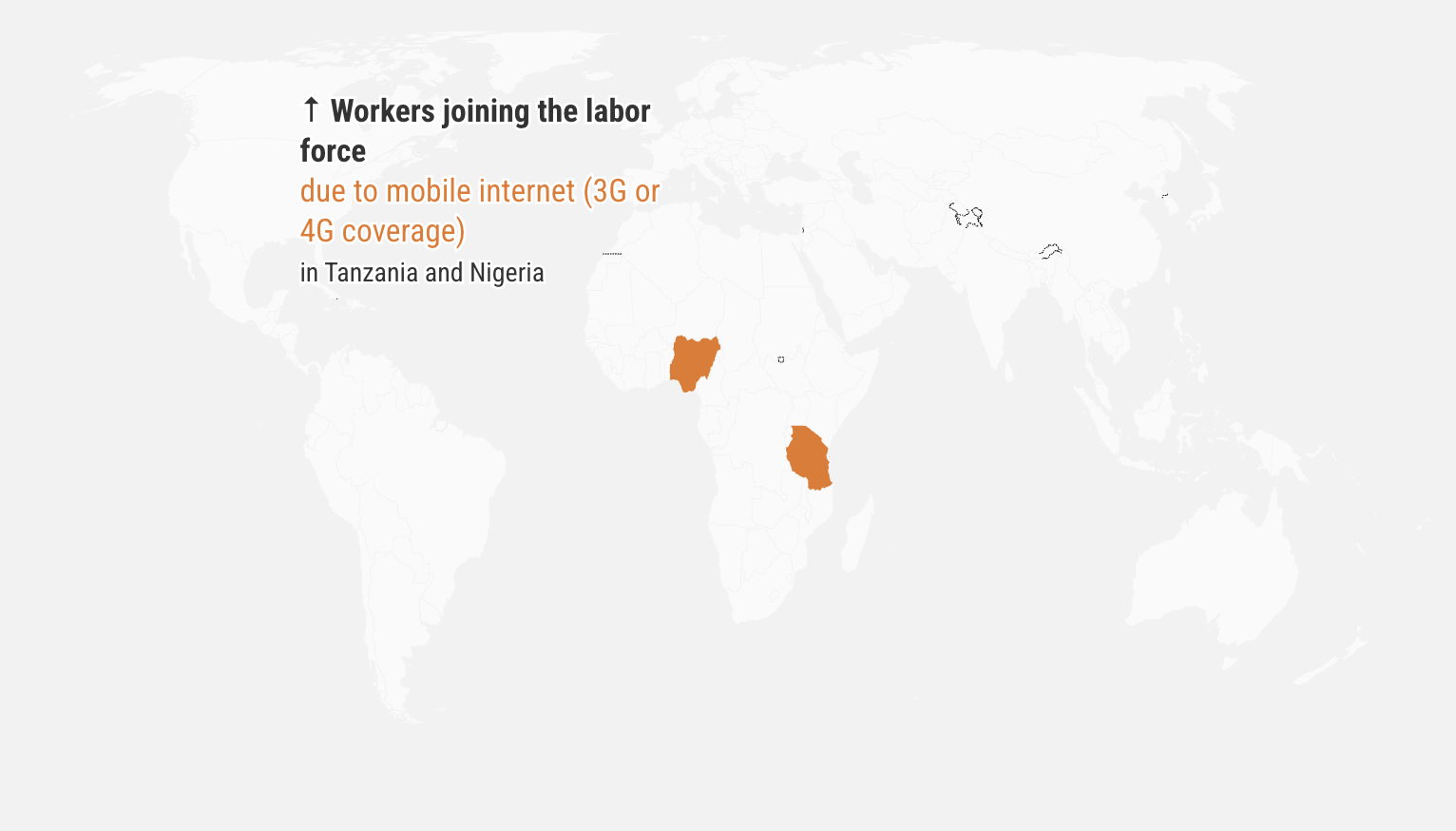

Analyzing quantity-based measures, expansion of broadband, and mobile internet is associated with significant increases in employment and labor force participation. Submarine cable connections in nine Sub-Saharan African countries, for example, increased employment by 13 percent over three years , while mobile coverage in rural South Africa raised employment by 15 percentage points over five years.

FIGURE 2

The impact of digital infrastructure on employment outcomes

FIGURE 3

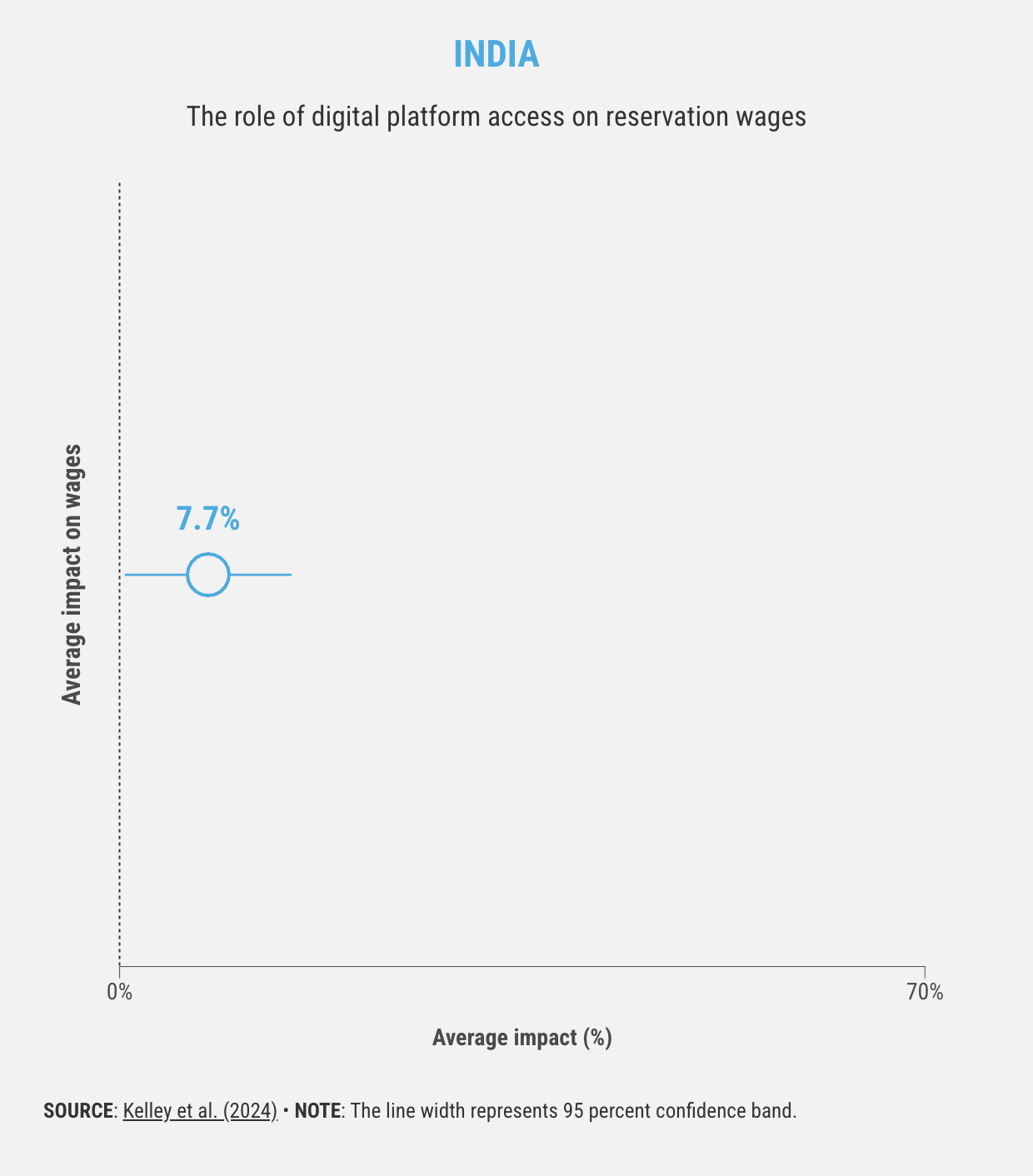

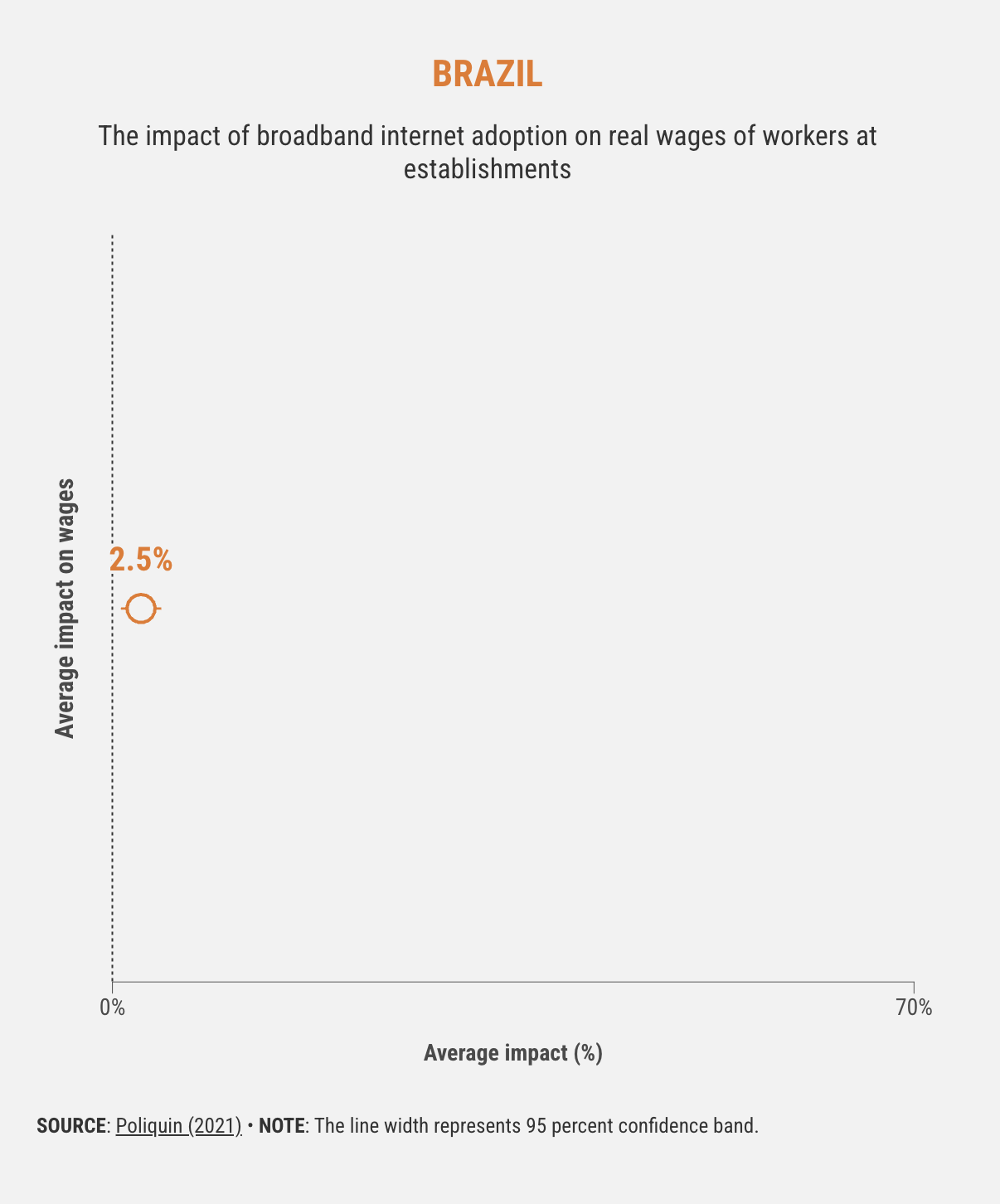

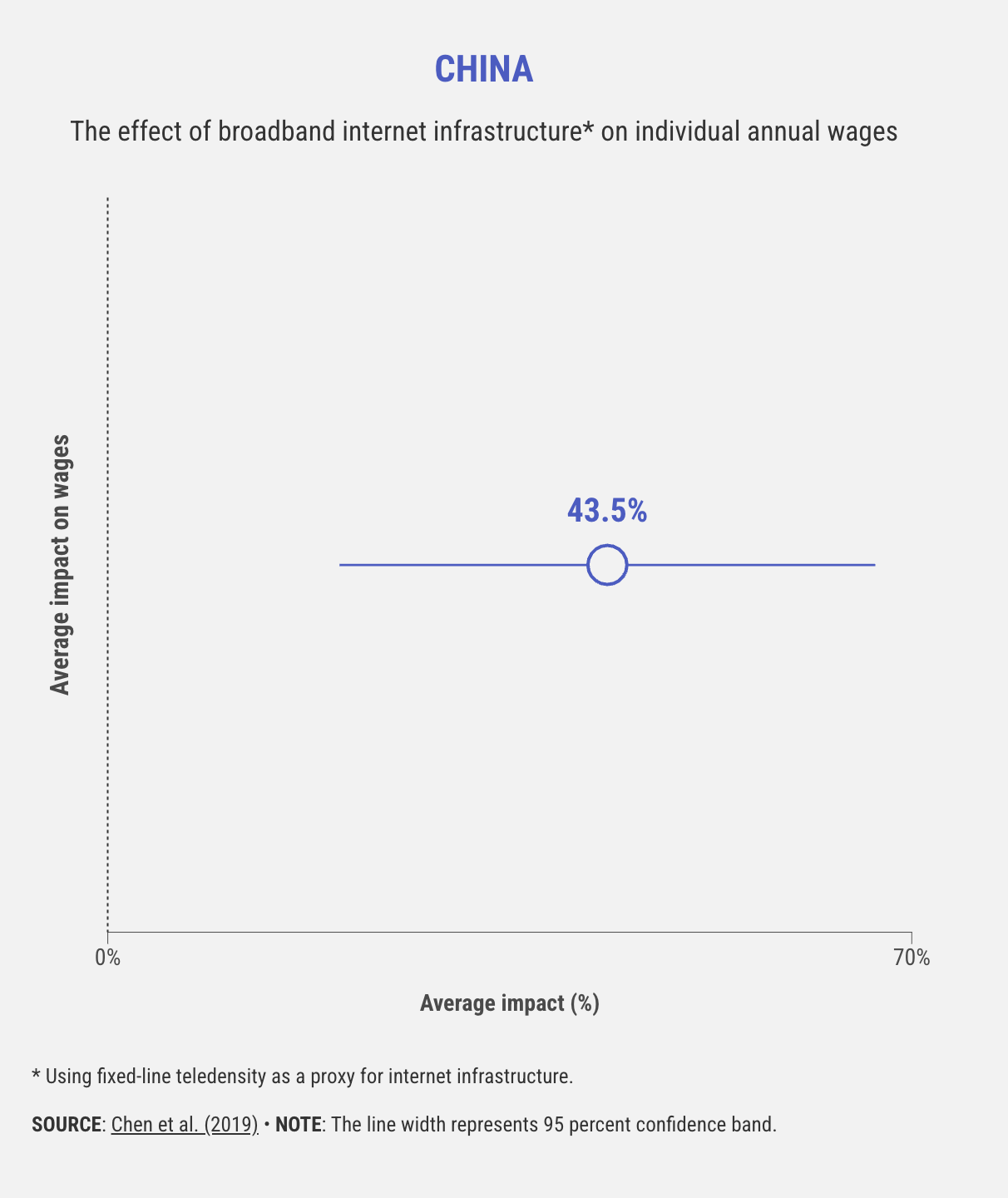

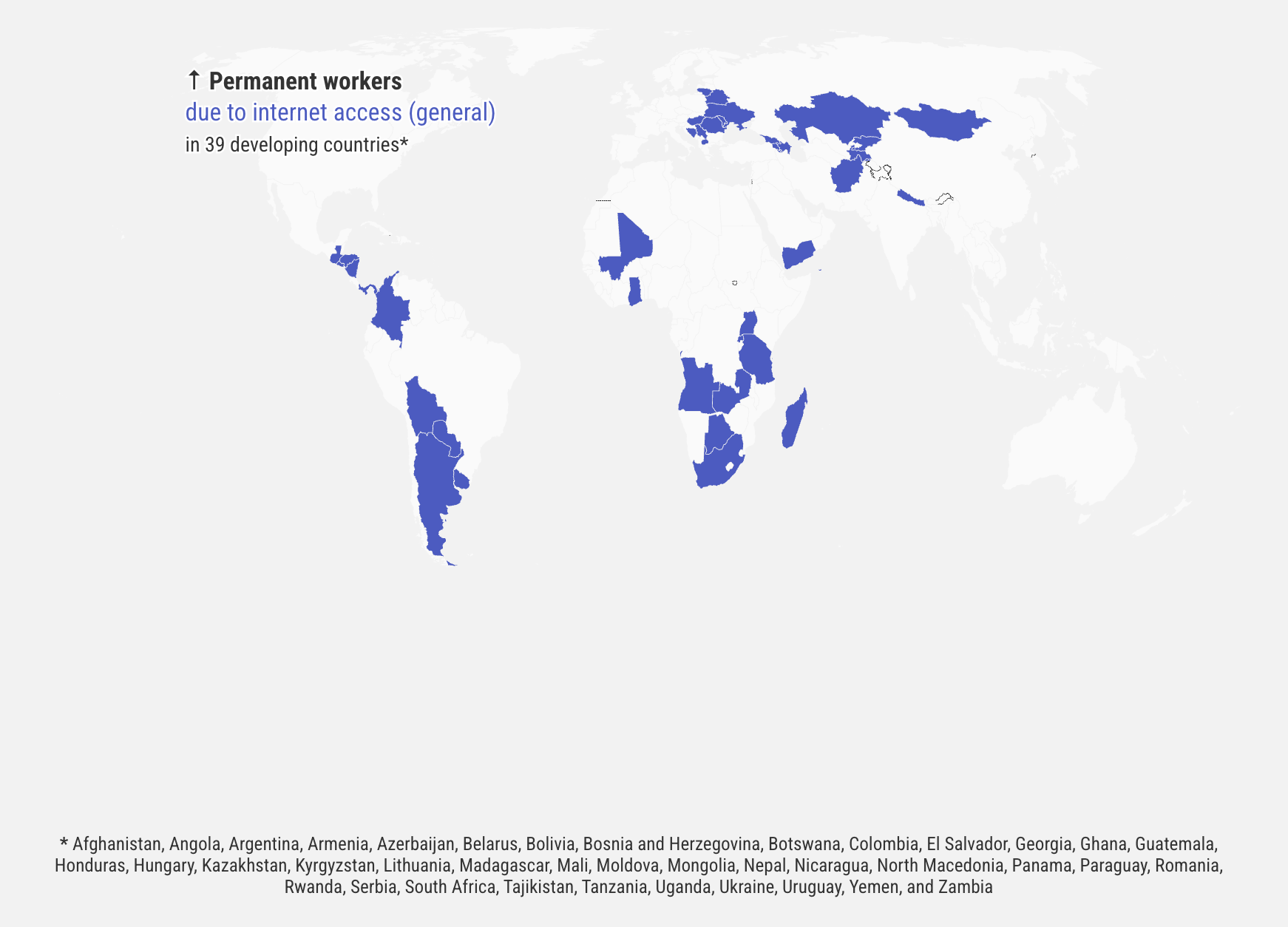

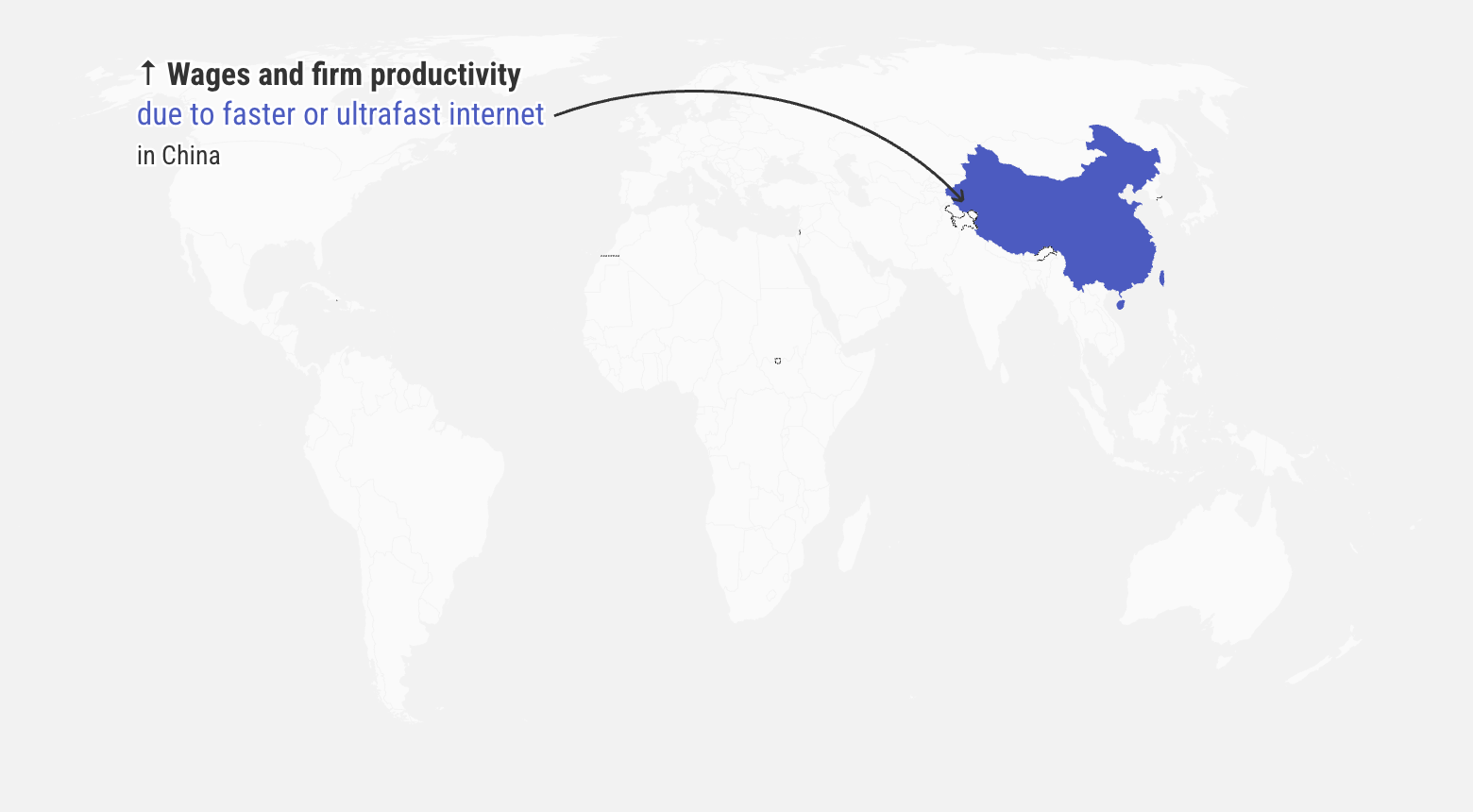

The impact of digital infrastructure on wages

FIGURE 4

Access to digital infrastructure improves total jobs and job quality across a range of countries and settings

JOB QUANTITY-BASED MEASURES

JOB QUALITY-BASED MEASURES

See this data as a table

Uneven Impact of Digital Connectivity

Digital connectivity has two competing effects that impact labor demand: automation and augmentation. As tasks are automated with digitalization, it may displace lower-skilled labor. Yet digitalization can also augment employment opportunities as it spurs firm growth by enhancing efficiency, opening access to new markets, and fostering shifts toward more competitive, digitally enabled activities or entirely new activities. Digital infrastructure may have uneven impacts across sectors, firms, occupations and skills, locations, and gender—carrying significant distributional consequences.

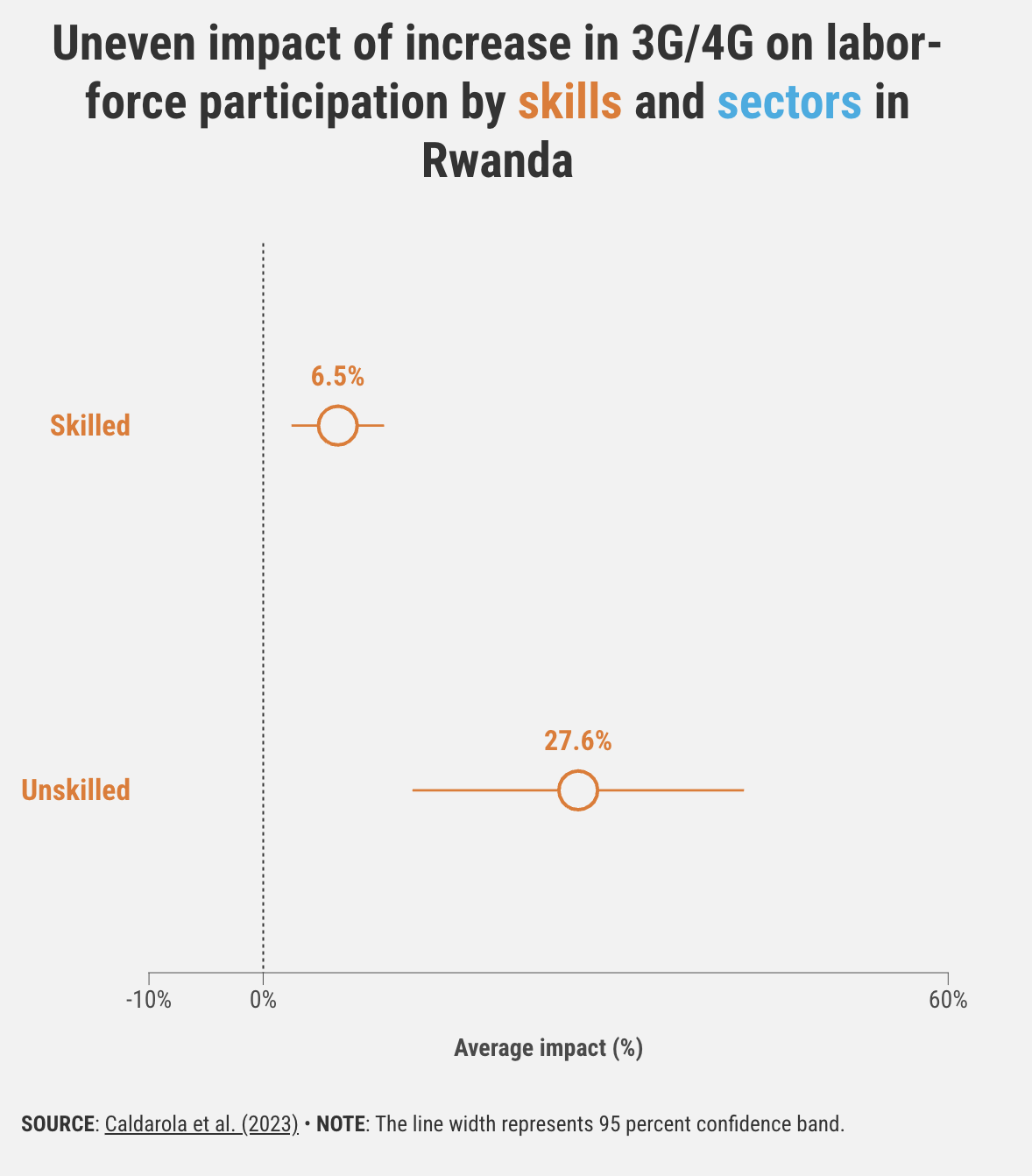

Occupations and Skills: While digital infrastructure in advanced economies has tended to reinforce generational and skill divides, evidence from emerging and developing economies is more positive. Firms with more educated and younger workers gained most from high‑speed internet in China, mirroring patterns seen in advanced economies, while studies from Rwanda and Tanzania find mobile internet boosting employment for both skilled and unskilled workers.

Firms: Given high upfront costs, larger, more productive firms and those with stronger management can adopt new technologies more readily. In Kenya, fiber-optic rollout primarily benefited larger firms, enabling them to expand buyer and supplier networks, while smaller firms struggled to invest in complementary capacity.

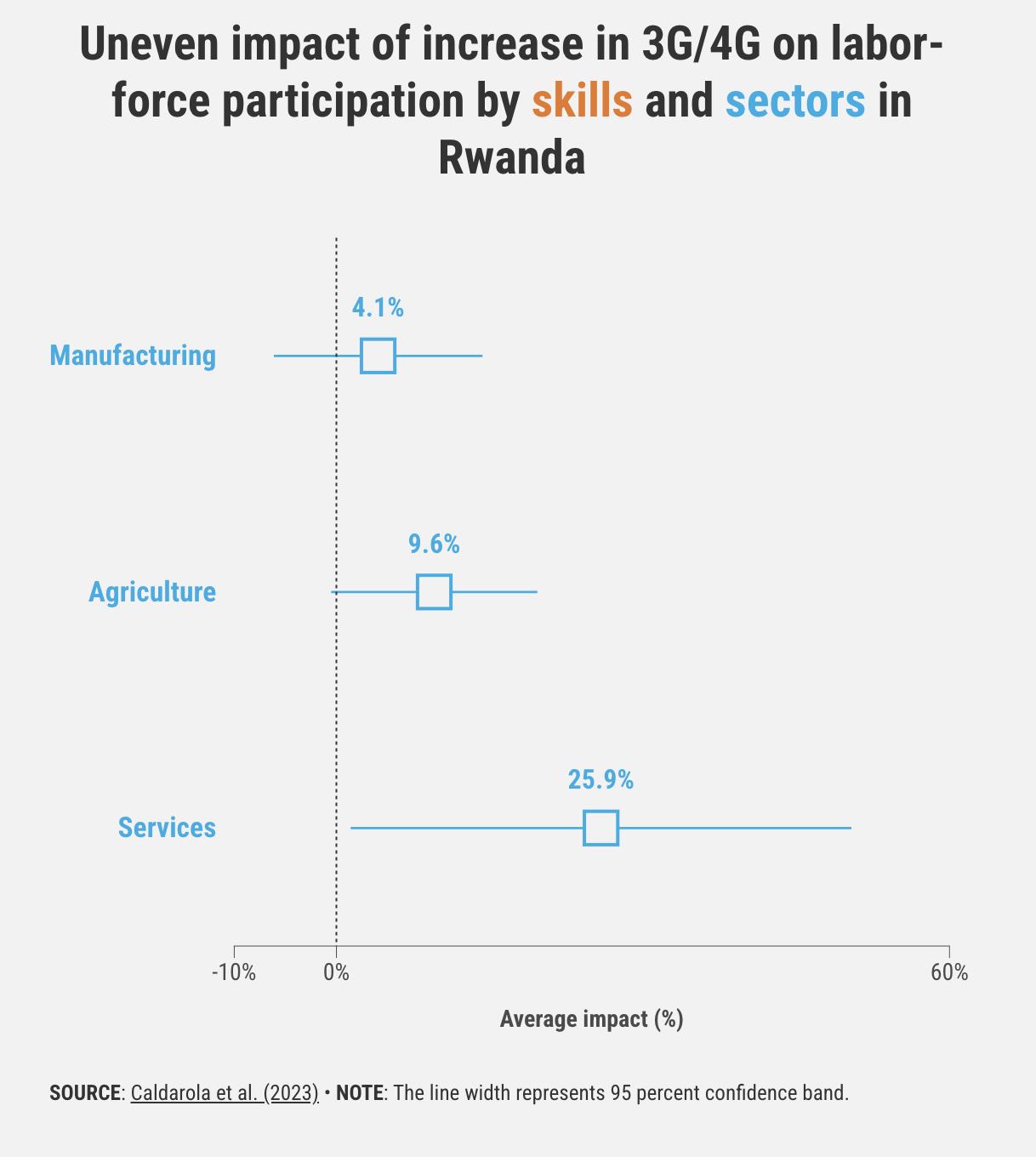

Sectors: Internet-enabled technologies often deliver larger benefits to services and skill-intensive industries, supporting structural transformation. For example, in Rwanda, improved 3G coverage shifted jobs toward services as well as high-value-added industries.

FIGURE 5

Locations: Regions with superior broadband exhibit labor market resilience, have higher business activity, and improve educational outcomes. It is not surprising then that internet expansion in poorer nations had stronger effects in reducing frictional unemployment and in supporting catchup growth.

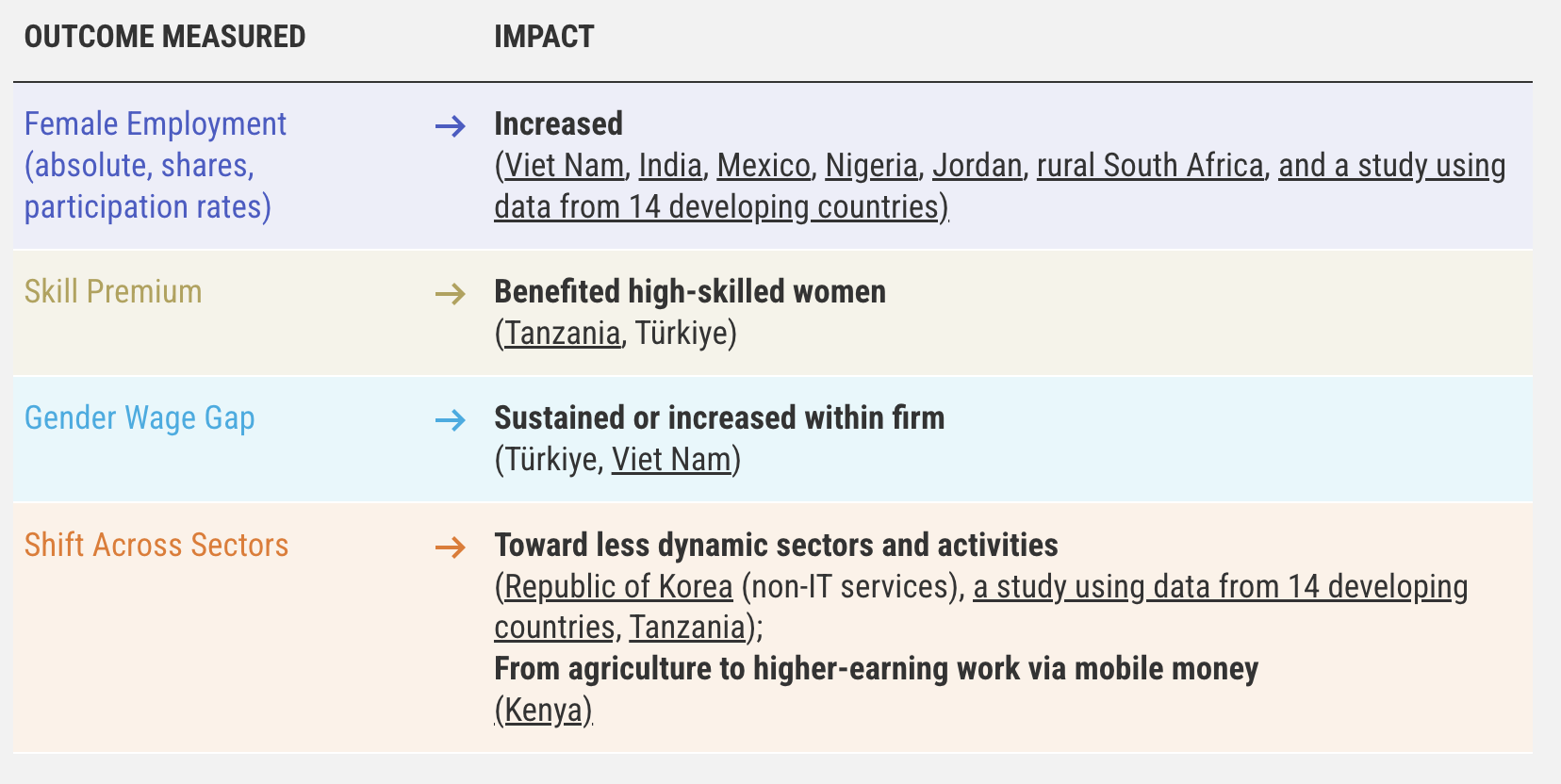

Gender: When digital connectivity improves, more women join the labor force. However:

- Benefits are larger for high-skilled women, suggesting that lower skill levels limit their ability to fully leverage the advantages of digital infrastructure.

- The gender wage gap may widen, possibly due to lower average education and skills among women, or social norms that inhibit occupational mobility.

- Women may shift toward lower value-added activities, such as unpaid agricultural roles and small businesses, which is partly explained by women taking up roles left by men transitioning to wage jobs. This contrasts with evidence from the impact of mobile money in Kenya that helped shift women from agriculture to higher-earning work.

FIGURE 6

Gendered effects of digital infrastructure adoption

The Way Forward

Nearly 68 percent of the global population is online, but only 27 percent of the population in low-income countries use the internet, risking exclusion from future job opportunities. Although developing countries have expanded digital infrastructure coverage, they still lag advanced economies in coverage and usage.

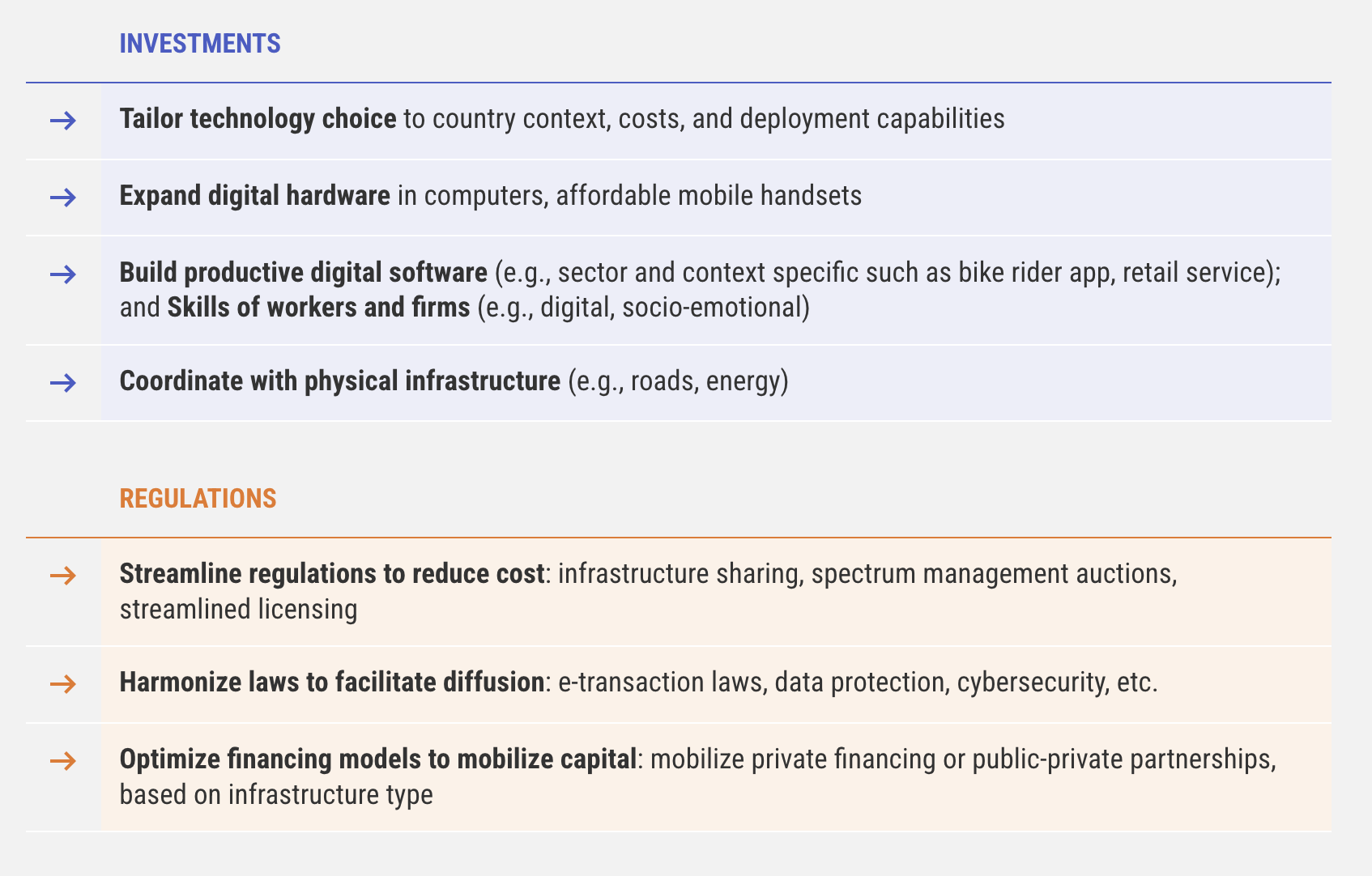

INVESTMENTS

Investments in submarine cables and so-called last-mile infrastructure, which connects the internet to workplaces and homes, can reduce prices by up to 21 percent and hasten digital adoption. However, closing the digital divide requires more than cables and towers.

Tailor Technology: Investments should be tailored to the level of development of the country or region. Although policies are often technology neutral, the choice between technologies can be critical, particularly due to their cost implications. For example, depending on capacity needs, the cost of achieving the UN’s goal of universal broadband in developing countries over the next decade ranges from $520 billion for 4G to $940 billion for 5G non-standalone digital connectivity, a hybrid upgrade from 4G that leverages existing infrastructure. The choice of technology depends on whether a country faces challenges with high traffic demand or the need to cover large, sparsely populated areas. Countries with high traffic demand, such as Pakistan, may benefit from 5G non-standalone digital connectivity to handle the load, while countries with wide geographic areas and low population density, such as Malawi, may find 4G a more cost-effective solution.

Expand Digital Hardware: To realize the benefits of infrastructure investments, they must be matched with investments in affordable devices. Access to mobile devices enables the use of digital platforms that addresses matching frictions and reduces price differences across space and sectors. Thus, they critically contribute to improved marketing decisions and resource allocation, and bolster nonfarm employment and entrepreneurship.

Build Specialized Digital Software and Skills: Digital platforms create new tasks and opportunities for micro and small businesses deploying specialized apps and digital platforms. To expand their use, three aspects are worth considering.

- Develop targeted and tailored platforms. For example, a mobile phone-based matching platform that connects agricultural buyers and sellers in Uganda reduced transaction level search costs by 21 percent, facilitating price convergence between regions. Job matching platforms such as Upwork and Freelancer expanded access to employment opportunities across borders, offering flexible arrangements especially beneficial to women and youth.

- Upskill workers. The new occupations that will emerge in the coming years are such that equipping workers with new or improved digital, social, and emotional skills will be essential to prevent labor-market bottlenecks. In this context, instruments such as retraining subsidies can ease the transition of displaced workers to new roles.

- Upgrade businesses. Training in the use of complementary technology tools and organizational practices, as well as R&D, will be essential to reduce the digital divide among large and small firms, for example.

Coordinate with Physical Infrastructure: The impact of digital infrastructure is amplified by complementary investments in road infrastructure, as estimated in Africa, where employment benefits can increase by 22 percent. Digital connectivity is critically dependent on energy infrastructure, implying that better electricity access boosts usage and attracts FDI in digital infrastructure. Multilateral development banks can forge innovative partnerships integrating energy and internet access to address the demand for reliable electricity and high-speed internet. For example, simultaneous investments in Fenix International and Lumos brought together mobile money with solar home systems in Africa.

REGULATIONS

Developing countries pay more and get lower-quality digital services than richer countries. For example, costs are 39 percent higher in Sub-Saharan Africa and 27 percent higher in Latin America. Three distinct areas of regulations are critical for cost, diffusion, and financing of digital infrastructure.

Streamline Regulations to Reduce Costs: Infrastructure sharing, for example, reduces duplication and can save on capital and operational costs by 15 to 72 percent. Effective spectrum management balances efficiency with equity. Streamlined licensing with long-term spectrum licenses provide regulatory certainty, whereas universal service funds help reach underserved areas.

Harmonize Laws to Facilitate Diffusion: Accessibility, security, and trust in digital use require harmonized regulations that enable secure online transactions, protection of data flows, and cybersecurity. Stronger policies are also needed to address anti-competitive practices in digital markets. Market integration can help reduce the prices of goods, services, and labor, which are essential to leverage potential gains from digital infrastructure.

Optimize Financing Models to Mobilize Capital: Financing digital infrastructure can leverage private, public, and public-private partnership models, contingent on regulatory simplification. For example, first-mile (submarine cables, data centers) can possibly be commercially viable through private-led investment (e.g., Google’s Equiano cable); middle-mile (national fiber backbones) could be more amenable to PPPs, such as with India’s BharatNet, which includes subsidies to attract private participation to expand rural broadband; while last-mile (rural and underserved areas) might need public financing to address viability gaps.

FIGURE 7

Investments and policies to leverage digital infrastructure for job creation

Unlocking the full potential of digital infrastructure—and the jobs it can create—hinges on mobilizing private investment. Forward-looking reforms that leverage digital collateral and, where appropriate, public guarantees and blended finance, are essential instruments to attract private investment. With these tools, emerging markets can leapfrog old limitations and ignite lasting job growth.

Editing by Scott Wenger; Infographics by Irina Sarchenko, IFC