At the 2025 AI for Good Global Summit, the workshop titled “AI for Human Rights: Smarter, Faster, Fairer Monitoring”, organized by the Geneva Human Rights Platform (GHRP) in collaboration with the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom Human Rights Hub, attracted strong interest from participants. The session explored how AI can support and reshape the way we monitor the implementation of human rights and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), while also highlighting the risks and challenges that the use of these technologies in such a sensitive field can bring.

At the 2025 AI for Good Global Summit, the workshop titled “AI for Human Rights: Smarter, Faster, Fairer Monitoring”, organized by the Geneva Human Rights Platform (GHRP) in collaboration with the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom Human Rights Hub, attracted strong interest from participants. The session explored how AI can support and reshape the way we monitor the implementation of human rights and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), while also highlighting the risks and challenges that the use of these technologies in such a sensitive field can bring.

What stood out was the strong interest in the topic: the session drew a large and engaged audience, with an attendance exceeding the room’s seating capacity. This served as a powerful reminder of just how timely and necessary the conversation around the implications of AI and human rights has become.

A workshop rooted in discussion and discovery

The workshop was designed to blend structured expertise in human rights and in AI with collaborative exploration. One of its key objectives was to bridge the knowledge gap between these two fields and facilitate meaningful exchanges between experts to build shared language and a mutual understanding of what responsible AI use in human rights monitoring should look like. The interactive segments also greatly benefited from the presence of data scientists and AI experts from ETH Zurich, including from its prestigious Center for Security Studies (CSS), who facilitated the group discussions and enriched the interdisciplinary exchange.

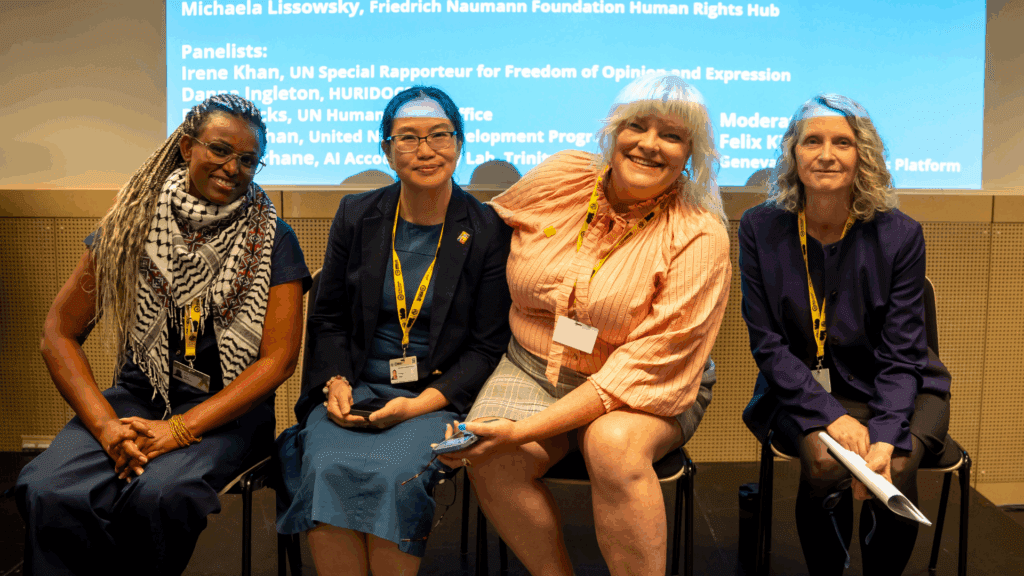

The session began with a high-level panel featuring Danna Ingleton (HURIDOCS), Peggy Hicks (UN Human Rights Office), Yu Ping Chan (UNDP), and Abeba Birhane (AI Accountability Lab), who shared insights from their respective organizations on the opportunities and risks of AI in human rights contexts. This was followed by interactive exchanges including live polling, a hands-on simulation with the UN Human Rights Office’s National Recommendations Tracking Database (NRTD), a demonstration of generative AI for building human rights monitoring prototypes, and discussions among participants to reflect on key insights and takeaways. By combining discussion with practical engagement, the workshop allowed participants to critically examine how AI is, and should be, applied in the field.

Watch the full session here:

Lessons from the panel: challenges and possibilities

The panel discussion offered diverse yet complementary perspectives, each underscoring the complexity of applying AI in human rights work.

For Danna Ingleton, the starting point is not technology itself, but its purpose. She emphasized that AI’s integration into human rights, especially in the field of documentation, must be critically assessed through the lens of its intended impact. Drawing from HURIDOCS’ experience supporting organizations worldwide with open-source tools like Uwazi, she cautioned against adopting AI just for the sake of innovation. AI, she argued, should serve the mission of amplifying the voices of human rights defenders, not obscure them through opaque automation or data practices that compromise privacy and dignity. Ingleton reminded us that AI must be community-led and grounded in justice, consent, and ownership.

Peggy Hicks emphasized that human rights and AI are not inherently at odds. The true risk lies in failing to systematically address the challenges these technologies present. Negligence, she noted, is a more common and insidious problem than malicious intent in AI use.

Yu Ping Chan brought in the SDGs perspective, stressing the importance of embedding human rights considerations from the outset of any development initiative, which applies to digital ones too. Ethical safeguards and human rights values, she argued, must be built into the architecture, not retrofitted after deployment.

Abeba Birhane highlighted the dangers not only of malicious intent but also of negligent deployment of overhyped and underperforming AI systems. Based on her work in algorithmic auditing and accountability research, she warned that AI tools are often marketed with capabilities they do not possess, making critical scrutiny essential.

What we learned from the community

Polling conducted during the session offered important insights into participants’ views. With 93 active contributors and 594 poll votes across eight questions, the results reflected a high level of engagement and interest in the topic.

Participants represented a broad spectrum of sectors, with academia (34%) being the most represented, followed by international organizations and civil society/NGOs (each at 22%). This composition brought together research, advocacy, and policy perspectives, contributing to a well-rounded discussion.

While most participants identified their AI knowledge as basic or intermediate, more than 50% reported advanced or expert-level experience in the field of human rights and development. This intersection of perspectives made the session particularly rich for critical reflection.

When asked how AI is already being used in their work, attendees mentioned monitoring violations, conducting research, using translation tools, and performing data analysis. Yet this optimism was accompanied by caution: the top concerns were privacy and data protection (55%), bias and discrimination (53%), and ethical and legal uncertainty (35%).

Perhaps most striking was the shared skepticism about the current state of AI tools: 73% of participants said today’s systems show very limited compliance with ethical and transparency standards for high-risk areas like human rights. Only 1% felt the tools were “largely responsible”, and none believed they fully met those standards.

What needs to happen next

Participants were also asked what kind of support would most improve the impact of AI tools in their work. The top priorities were clear: stronger ethical and legal guidance (63%), more reliable and representative data (53%), and capacity-building (49%). These responses echoed the reflections shared during the panel.

The practical segments of the workshop further highlighted the importance of human oversight. Both the hands-on simulation with OHCHR’s NRTD, which demonstrated how AI might assist in planning and tracking follow-up on human rights recommendations, and the generative AI prototype showcase reinforced one key point: if AI is to support human rights effectively, it must do so through a human-in-the-loop approach. Automation alone cannot capture the nuance, context, and accountability required in rights-based work.

Why these conversations matter

The key takeaway from this workshop is not simply that AI holds promise for human rights, that much is widely recognized. Rather, it is that the responsible integration of AI requires open, inclusive, and ongoing dialogue, grappling with both its potential and its pitfalls. Technology alone cannot resolve the structural, political, or ethical challenges that human rights work must confront.

Spaces like this workshop help build common understanding and trust across sectors. They pave the way for solutions that combine innovation with integrity, solutions that must be shaped not just in expert forums, but also in national institutions, civil society networks, and, most importantly, among the communities directly affected.

As one participant put it: “This gave me a new perspective, not just on what AI can do, but what it should do.” That question, what AI should do, is one we must keep asking together.

As these discussions continue, it is clear that building bridges between the human rights and AI communities remains an important priority. This workshop demonstrated the value of dialogue, not only to surface shared concerns, but to lay the groundwork for responsible, people-centered innovation. The conversation is just beginning and it must remain inclusive, critical, and grounded in the lived realities of those it aims to serve.